Many countries' coronavirus curves are flattening, at least for now.

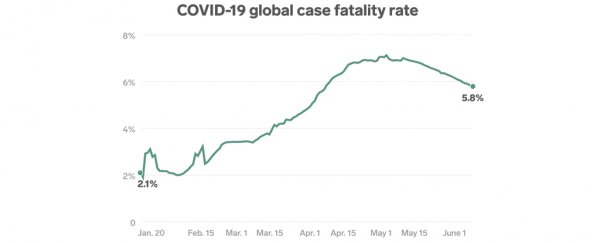

Yet somehow, the global case-fatality rate has increased significantly since March, when it was around 3.4 percent. The rate was 5.8 percent on Tuesday, according to tallies from the World Health Organisation, and it hovered around 7 percent from mid-April through May.

The trend runs contrary to many experts' earlier expectations: that testing would increase, leading more mild cases to be recorded and the death rate to go down.

But it seems testing has not increased enough to result in a significant downward trajectory.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS/TAMU)

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS/TAMU)

The coronavirus death rate is not as simple as it appears

As governments prepare for new waves of infection and consider the tradeoffs of lockdowns, a crucial question informs how they move forward: Just how deadly is COVID-19?

The most straightforward answer may seem to be the case-fatality rate, a calculation of the number of known deaths out of the total number of confirmed cases.

But because coronavirus cases progress over a period of weeks, and because the numbers are constantly changing, the death rate is always in flux.

Some epidemiologists say that because death rates are so heavily influenced by testing and delays in reported cases and deaths, they're simply not a reliable measure of the virus's toll over time.

Many countries aren't testing enough

When asked about the increase in global death rate, Ben Cowling, head of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Hong Kong School of Public Health, had a simple answer: "Not enough testing of mild cases."

In general, the more cases that are included in the data – including people with mild or no symptoms – the lower the death rate.

In that sense, case-fatality rates "are more a measure of how much testing and case finding you do," John Edmunds, a professor of infectious-disease modelling at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, told Business Insider.

"Look at Singapore and South Korea for comparison, where there is a lot of testing," Cowling said.

South Korea, which has tested more than 1 million people, far outpaced other countries in early case detection and contact tracing. While US labs waited for weeks for instructions on how to fix faulty test kits in February, South Korea was testing tens of thousands of people.

The country's death rate was 2.3 percent as of Wednesday. Singapore, which has also been lauded for its wide-reaching testing, had a death rate of just 0.1 percent.

Limited testing in other countries, like Sweden and the US, make their case counts inaccurately low. In the US, experts think we need to multiply the official confirmed case count by 10 to get an accurate estimate of true infections nationwide.

"There is no way that we record all the cases, though we probably record most of the deaths," Edmunds said.

(Ruobing Su/Business Insider)

(Ruobing Su/Business Insider)

When countries miss many mild cases, deadly cases seem like a higher proportion of infections than they really are. Countries like the US and Sweden, therefore – which have case-fatality rates of 5.7 percent and 10.3 percent, respectively – could be inflating the global death rate.

Death rates can seem highest after an epidemic peak

New deaths reported now are generally people who fell ill three to four weeks ago. That's when many countries' outbreaks were still peaking. So even once daily case counts fall, daily deaths can continue to climb.

"Mortality will spuriously spike when cases are decreasing," William Hanage, an epidemiologist at Harvard's TH Chan School of Public Health, told Business Insider.

"The reason is that you are seeing the deaths from when the epidemic was expanding, or at least more intense than it is now, while your total case counts are up to the present."

The fact that death tolls lag behind case counts can briefly create a very high death rate. That's what seems to have happened in April and May. (And limited testing can magnify that effect.)

To get a more accurate picture of how deadly the virus is, Edmunds said, "what you need to do is take account of the delays properly, so effectively you need to divide deaths today by cases that occurred three to four weeks ago."

That maths suggests the virus has killed roughly 1 percent of the people who tested positive four weeks ago. But again, since that doesn't include many people with mild or asymptomatic cases, the true proportion of people who die after being infected is probably much lower.

Experts like Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, have also estimated that the true death rate is closer to 1 percent. A May study from the University of Washington suggested that if all infections were known, the true death rate for Americans who show symptoms would be about 1.3 percent.

That's far lower than what case-fatality rates suggest, but it's still 13 times higher than the death rate of the seasonal flu.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: