There are plenty of us who want to lose a little (or a lot of) weight, but despite all the research being done into how to trigger this process, there's still a lot we don't know about fat cells. Case in point, researchers in the US have just discovered that fat cells metabolise different nutrients as they mature.

The research is limited to the lab for now, but it could help to explain why some people with obesity and diabetes find it so hard to lose weight. It also suggests new potential weight-loss treatments for these individuals.

"This study highlights how specific tissues in our bodies use particular nutrients," said lead researcher Christian Metallo from the University of California, San Diego. "By understanding fat cell metabolism at the molecular level, we are laying the groundwork for further research to identify better drug targets for treating diabetes and obesity."

What Metallo's team found is that cells change their diet from when they're pre-adipocytes – the precursors to fat cells – to when they're fully-fledged adipocytes, which are those jerk cells that specialise in storing fat and making us put on weight.

The researchers developed these pre-adipocytes in the lab and showed that in the early stages, they broke down glucose, a simple sugar, to grow and make energy. But as they matured they didn't just stop at glucose, they also start metabolising a small group of essential amino acids, known as branched-chain amino acids.

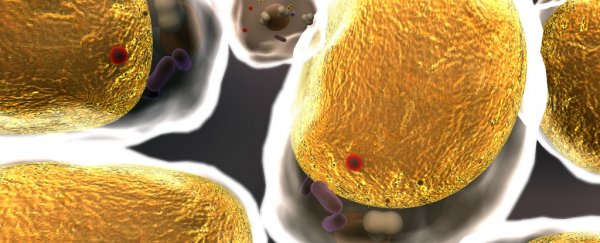

Metabolic Systems Biology lab at UC San Diego

Metabolic Systems Biology lab at UC San Diego

This is interesting, because even though we all have these branched-chain amino acids in our bodies, the levels in people with diabetes and obesity are typically much higher, and scientists haven't been able to figure out why.

"We've taken a step towards understanding why these amino acids are accumulating in the blood of diabetics and those suffering from obesity," said one of the researchers, Courtney Green. "The next step is to understand how and why this metabolic pathway becomes impaired in the fat cells of these individuals."

The obvious thing to do would be to get the body to stop producing branched-chain amino acids in an attempt to starve or slow the growth of mature adipocytes. But unfortunately we need these amino acids to survive, so that's not an option.

Instead, the team is trying to learn more about the biochemical pathways that fat cells use to grow in the hopes of finding a way to hijack this process.

"We are curious about how different cells in our body, such as fat cells, consume and metabolise their surrounding nutrients," said Metallo. "A better understanding of how these biochemical pathways are used by cells could help us find new approaches to treat diseases such as cancer or diabetes."

The research has been published in Nature Chemical Biology.