Analysis of a perfect jawbone found in Taiwan has given us new clues to the Denisovans, an enigmatic people with whom our ancestors had relations.

Once upon a time, Homo sapiens wasn't the only human species walking the planet. We shared this world with multiple long-lost relatives, a history of intermingling written in our genomes.

The most famous and well-known of these are the Neanderthals. But, further to the east, another, smaller relative once made their home. These were the Denisovans, who we know very little about, due to the scarcity of their remains.

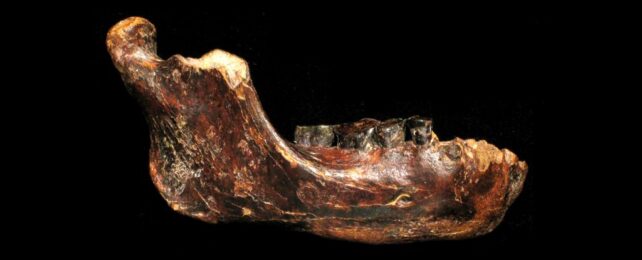

Named Penghu 1 by archaeologists, the jawbone is the most intact Denisovan fossil of the less than 15 identified to date, and the first discovered in Taiwan.

Denisovan remains have been found in Siberia, in Denisova Cave for which they are named; in China, in Baishiya Cave on the Tibetan Plateau; and one possible Denisovan tooth in a cave in Laos, although that one may be Neanderthal.

Most of these remains are either bone fragments or teeth. A complete Denisovan skeleton has never been identified. While genetic analysis suggests they diverged from Neanderthals a few hundred thousand years ago, the precise timing of their migration across Asia or their eventual demise isn't clear.

Dating of sediment layers in Denisova Cave suggests that the Denisovans occupied the space between 300,000 and 50,000 years ago. That's the best information we have so far.

We also know, based on the remnants of Denisovan DNA in modern humans, that they were probably significantly more widespread than their remains suggest.

Despite being hauled from the ocean some 25 kilometers (15 miles) off Taiwan's western coast over a decade ago, Penghu 1's story has been as murky as the sediment it lay in for thousands of years.

Beyond belonging to a member of the hominid family, a more precise identity remained elusive, with an attempt to recover DNA unsuccessful.

Now, a team of scientists led by the Graduate University for Advanced Studies in Japan and the University of Copenhagen have taken another crack at it… and cracked the mystery wide open.

Their research was based on, not DNA, but a series of techniques collectively called ancient protein analysis, or paleoproteomics. This process involves extracting proteins from the bone and tooth enamel of ancient remains, subjecting them to techniques such as mass spectrometry, and using them to build a profile of the individual in question.

After removing likely contaminants and potentially biasing factors, the team was left with 22 proteins that provided 2,218 amino acid residues that could be used to put the fossil in context with Denisovans, Neanderthals, ourselves, and other great apes. Comparison confirmed that the jawbone is indeed of hominid origin… and two amino acid sequence variants of the thousands sampled were exclusive to Denisovans.

They also found proteins specific to the male sex, revealing that Penghu 1 belonged to a male Denisovan who lived tens of thousands of years ago – some 4,000 kilometers southeast of Denisova Cave, and 2,000 kilometers southeast of Baishiya Cave.

We don't know exactly when Penghu 1 lived; so far, attempts to date the mandible have returned a wide range of between 10,000 and 190,000 years old. What the bone does tell us is that Denisovans had larger molars and more robust jawbones than Neanderthals, a difference that likely emerged after the two groups diverged between 300,000 and 400,000 years ago.

"The identification of Penghu 1 as a Denisovan mandible confirms the inference from modern human genomic studies that Denisovans were widely distributed in eastern Asia," the researchers write in their paper.

"It is now clear that two contrasting hominin groups – small-toothed Neanderthals with tall but gracile mandibles and large-toothed Denisovans with low but robust mandibles (as a population or as a male character) – coexisted during the late Middle to early Late Pleistocene of Eurasia."

We may never truly have a comprehensive picture of who the Denisovans were and how they lived, but this is a spectacular discovery that takes us just a little bit closer to understanding this enigmatic piece of the human puzzle.

The research has been published in Science.