When the Black Death ravaged Europe midway through the 14th century, it wiped out around half of the population with deaths so swift, people had to bury countless victims in mass graves. At least that's the story archaeological remains have told us until now.

Researchers have just unearthed new evidence suggesting mass burials are only one side of the devastating story wrought by the plague because, as it turns out, some victims were laid to rest in their own graves with great care.

The University of Cambridge team behind this new study sampled nearly 200 graves and detected ancient DNA of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes the plague, in the teeth of some people who died from the disease and were buried alone.

"This [research] greatly improves our understanding of the plague and shows that even in incredibly traumatic times during past pandemics people tried very hard to bury the deceased with as much care as possible," says University of Cambridge archaeologist and lead author Craig Cessford.

The discovery adds a new dimension to the plague's long and horrible history, which stretched on for years after the Black Death of 1346 to 1353 in what became known as the second plague pandemic (after the first, a few centuries earlier).

Even to this day, outbreaks of the plague still emerge, in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, and Peru. China and California have also recorded cases in recent years, though the disease can now be treated with modern antibiotics, if available.

But people in the Middle Ages had a couple more centuries ahead of them before the cause of this deadly disease, Y. pestis, was described by Swiss-French bacteriologist Alexandre Emile Jean Yersin in 1894.

Fearing the contagious disease that killed people within days, victims were buried in mass graves, or 'plague pits', such as the one unearthed at a 14th-century monastery in northwest England. It contained 48 skeletons, and over half were children.

The archaeologists behind that dig had thought that some of these people – even though they were laid to rest in mass graves – had been buried with care, possibly wrapped in shrouds, based on the compression of the skeleton's shoulders. But it was a hunch that needed more evidence to stick.

Armed with DNA sequencing techniques, the University of Cambridge team set to work sampling over 190 skeletons from five burial grounds in and around Cambridge, including a friary, urban hospital cemetery, and a church, hoping to find ancient DNA preserved in the teeth of people who succumbed to the plague.

The remains, mostly unearthed in singular burial plots and one mass grave, were dated to between 1349 and 1561, so these people likely died during the second plague pandemic. This was confirmed in 10 of the 197 skeletons analyzed, which tested positive for Y. pestis.

"These skeletons have previously been almost impossible to recognize and attention has thus focused on the exceptional mass burials" because the fatally fast disease "leaves no visible traces on the skeleton," writes Cessford and his colleagues.

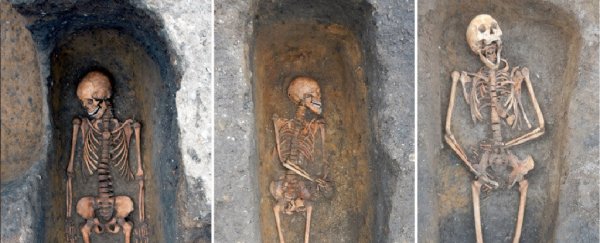

Individuals buried in the friary chapter house who died of the plague. (Cambridge Archaeological Unit)

Individuals buried in the friary chapter house who died of the plague. (Cambridge Archaeological Unit)

With DNA evidence confirming the remains are those of plague victims, "these individual burials show that even during plague outbreaks individual people were being buried with considerable care and attention," explains Cessford.

"Particularly at the friary where at least three such individuals were buried within the chapter house," and a fourth person was also carefully buried at a nearby church, says Cessford.

The most striking aspect of the way these plague victims were buried, as Cessford and his colleagues explain in their paper, is the effort people must have invested in burying their kin within the chapter house walls.

"The chapter house had a mortared tile floor; dozens of the tiles would have to be carefully lifted before a burial was inserted and either reinstated or replaced with a grave slab afterwards," they write.

"This [also] contrasts with the apocalyptic language used to describe the abandonment of this church in 1365 when it was reported that the church was partly ruinous and 'the bones of dead bodies are exposed to beasts'," Cessford adds.

The team did find some people who had received mass burials and tested positive for Y. pestis, which is a good comparison, but in finding the first evidence of medieval plague victims buried alone thanks to ancient DNA, the study opens a new chapter for archaeologists.

Cessford and his colleagues say it could be the start of a big shift in our archaeological understanding of societies facing severe epidemic outbreaks, writing that the discovery draws a "more comprehensive picture of frailty and resilience in past societies."

"If emergency cemeteries and mass burials are atypical, with most plague victims instead receiving individual burial in normal cemeteries, this calls into question how representative these exceptional sites are," the team concludes.

It also makes you wonder what story will remain of the coronavirus pandemic that scourged 2020 and is not done yet.

The study was published in the European Journal of Archaeology.