A shark sheds up to 40,000 teeth in its lifetime – and megalodon, the greatest predator of them all, was no different.

As this fearsome beast roamed the world's oceans between 4 and 20 million years ago, it dropped teeth that are still washing up on beaches, found sticking out of whale bones, or rising out of once-submerged landscapes.

But until now, none have been discovered in much the same position that they fell into all those millions of years ago.

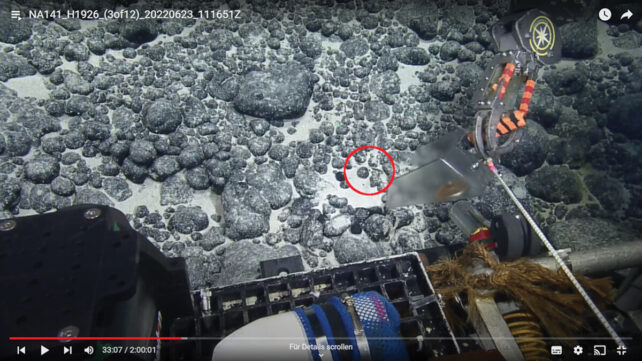

A team of intrepid researchers has just described one such find: a fossilized Otodus megalodon tooth partially embedded in the ocean floor, some 3,000 meters (or 1.9 miles) below the surface, in the vastness of the Pacific Ocean.

The tooth was hard to spot amongst the rocky outcrop, but researchers viewing footage from a remotely operated submersible spotted it sticking straight up out of the sand, as if it had plonked down just moments ago.

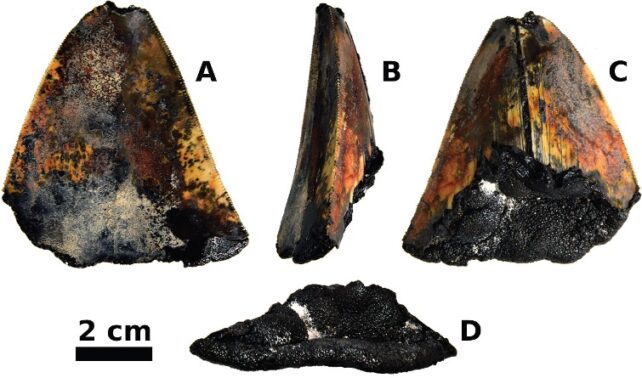

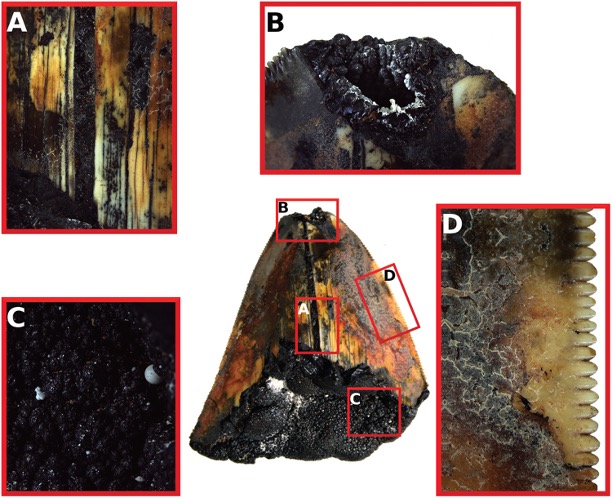

When they inspected the ancient tooth back on dry land, they found it had a broken tip and serrated edges that look almost as sharp as the day they last sliced through fresh meat.

Megalodon's fearsome physique, large enough to eat up modern-day sharks in a few bites, is known almost exclusively by its teeth – which can be as big as a human hand – and scattered vertebrae. Unlike these robust pieces of anatomy, the rest of O. megalodon's soft tissue and cartilage haven't survived the 3.6 million years since the beast went extinct.

Based on that departure, this particular tooth is thought to be at least that old. It was found in a remote location southwest of Hawaii, a few hundred kilometers from a US military outpost called Johnston Atoll, on the edge of an ocean 'desert'.

Researchers aboard the Exploration Vessel (EV) Nautilus had been surveying the area to understand more about its deep-sea geology and biology.

"There are areas of the seafloor, especially deep ocean basins far from the mainland, where little to no sediment deposition occurs for long periods of time," Tyler Greenfield, a paleontologist at the University of Wyoming, explains.

"It's also possible for teeth to be eroded out and reworked into younger sediments, but that probably didn't happen in this case."

The tooth was found on the crest of a ridge, where ocean currents are thought to be strong enough to stop sediment from accumulating. The serrated edge of the tooth was also exceptionally well preserved, which suggests the tooth hasn't been tossed and tumbled, and therefore eroded.

While not the biggest of its kind, the newfound tooth (which measures a modest 63-68 millimeters or 2.5-2.6 inches) adds to a growing number of specimens that are tracing megalodon's movements across oceans.

Looking back at historical records of past deep-sea expeditions, Jürgen Pollerspöck, of the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology in Germany, and colleagues identified numerous other megalodon teeth that have been scooped up from depths of 350 to 5,570 meters. But they say this was the first one documented in its final resting place, as it was found.

"The first in situ documentation of a megatooth shark fossil from the deep sea highlights the importance of using advanced deep-diving technologies to survey the largest and least explored parts of our ocean," the team concludes.

The study has been published in Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology.