The most elusive planetary aurora in the Solar System has finally been revealed in all its gently glowing glory.

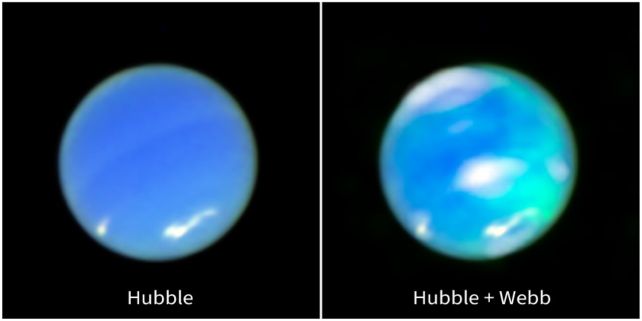

Far from the Sun, and Earth, the sky-blue planet Neptune has been captured shimmering in near-infrared light as particles interact in its hazy atmosphere.

It's the first time an aurora has been imaged on the Solar System's outermost known planet, thanks to the sensitivity of JWST's powerful near-infrared spectrometer.

At last, the set is complete. Auroras have been seen on every single planet in the Solar System, revealing that the phenomenon is not just widespread, but a feature of the interaction between planets and the Sun.

The phenomenon does, however, look very different depending on the world on which it appears. Earth's auroras are the most spectacular, a panoply of colors that light up the sky when particles from the solar wind slam into Earth's magnetic field, where they rain down into the upper atmosphere.

The interaction between these incoming particles and the atmosphere's resident particles causes dancing, glowing lights.

Jupiter has the most powerful, energetic auroras in the Solar System, permanent caps of bright ultraviolet light. Actually, its four largest moons have auroras, too. Saturn likewise has ultraviolet auroras, as does Mars. Venus has green auroras, much like those seen on Earth.

Mercury's aurora is, perhaps, the strangest; because it has no atmosphere, the aurora manifests as X-ray fluorescence from the interaction between solar particles and minerals on the surface.

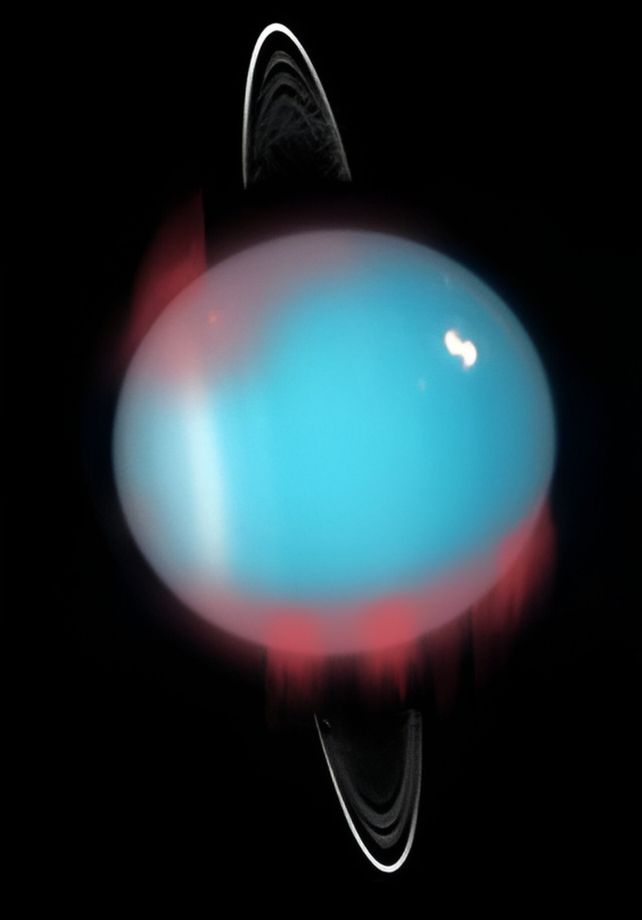

For a long time, it was unclear what auroral activity, if any, might be present on Uranus and Neptune, so far from the Sun: Uranus orbits at around 19 times the distance between the Sun and Earth, and Neptune at around 30 times.

In 2023, an analysis of archival data confirmed the presence of infrared auroras at the Uranian equator. Now, JWST data has proven the existence of similar auroras at Neptune.

In 2023, the space telescope obtained a detailed spectrum of Neptune's atmosphere, revealing the clear presence of the trihydrogen cation (H3+) – a positively charged form of trihydrogen associated with auroras.

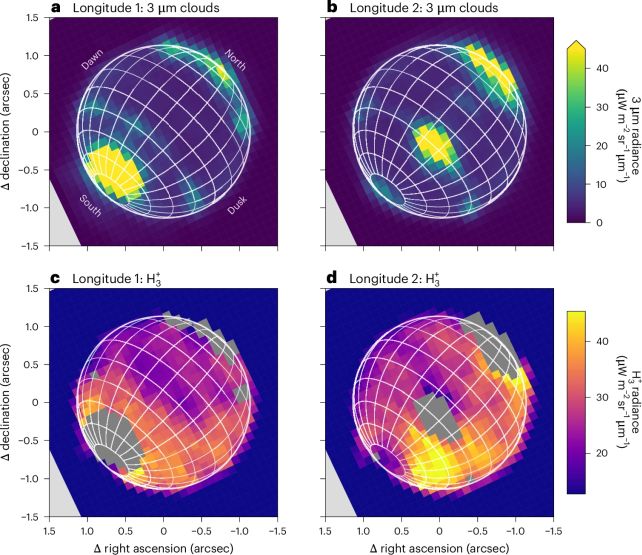

By tracking the concentration of H3+ across the skies of Neptune, a team of astronomers led by Henrik Melin of Northumbria University in the UK was able to map the location of the planet's auroras.

Interestingly, a quirk of Neptune's magnetic field meant that its auroras were not where they would appear here on Earth. The lines of our planet's magnetic field converge around the poles; when solar particles are whisked away and dumped into the atmosphere, high latitudes are the focal point of the dumping.

Neptune and Uranus both have very messy, lopsided magnetic fields. On Neptune, the dumping point for solar particles is near the planet's equator, rather than the poles.

JWST measurements of the temperature of the distant ice giant also revealed why we've had such a hard time detecting Neptune's auroras. Temperatures of Neptune reported by Voyager 2 measurements – the only human-made spacecraft to have ever neared the planet – were much higher than those detected by JWST, suggesting the planet has cooled significantly since 1989.

Colder temperatures mean fainter auroras. Previous predictions about Neptune's possible auroras were based on inaccurate temperatures, so scientists had been looking for the wrong thing.

This discovery gives us a new tool to interpret, not just the variety that can be exhibited by a single phenomenon across very different worlds here in the Solar System, but also on other worlds orbiting alien stars.

"Since the most commonly detected type of extrasolar planet is Neptune-sized, and as Neptune lacks the extreme seasons of Uranus," the researchers write in their paper, "these observations provide a new diagnostic to probe atmosphere-magnetosphere interactions on the most common-sized worlds in our galaxy."

The research has been published in Nature Astronomy.