Researchers have made a significant breakthrough in the development of the first-ever vaccine for the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a virus that causes infectious mononucleosis (IM, or 'mono') – also known as glandular fever.

The virus can infamously lead to further health issues like cancer and multiple sclerosis (MS).

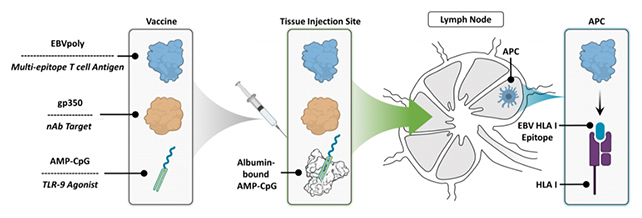

The team of scientists, from the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Australia, have been able to design a vaccine targeting lymph nodes in mice, which are key players in the functioning of the body's immune system.

Not only did the vaccine produce strong, long-lasting antibodies and T cells to fight EBV, it was also shown to induce a particular kind of immunity to protect against the growth of EBV-associated tumors. By blocking EBV activity early, the drug prevents secondary issues, like brain inflammation that can lead to MS.

That combination of antibodies and T cells, which both play different but very important roles in the immune system, is crucial. Antibodies bind to unwanted, invading pathogens to eliminate them, while T cells directly destroy these pathogens and help coordinate the body's defenses.

"What we have done is we have designed what we call another arm of the immune system, that we call T cells, and combined that with antibody, and this new formulation will induce both – both the antibody and the T cell immune response," says Rajiv Khanna, an immunologist at the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute.

"It is now very much well established that to give long-term protection against EBV-associated diseases, you don't only just need antibodies but also the T cell immunity."

EBV is a member of the herpes family of viruses and can be passed around through saliva. Although at least 95 percent of the world's population have the virus, for most of us that happens at a very early age, and doesn't lead to any serious symptoms. The virus is then carried harmlessly around with us for the rest of our lives.

Problems happen when someone doesn't get that early dose and is infected with EBV later on, especially in adolescence. That's when the effects of the virus can be much more severe, leading to mono (or glandular fever), and an increased risk of certain kinds of throat and nose cancers as well as multiple sclerosis.

Scientists are busy trying to limit the damage done by EBV in the body, and part of the challenge is figuring out how the virus manages to be so destructive for some people and barely noticeable for others.

When it comes to human clinical trials, the team already has some funding from industry partners, and is looking for more to make the trials as comprehensive as possible. Those trials could start in 2024 or 2025 if all goes well.

"It has been very satisfying," says Vijayendra Dasari, a vaccine development scientist from the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute. "Now we are kind of getting close to the final stages of development."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.