In Hungary, a grave worthy of Katniss Everdeen – complete with a bow and an armor-piercing arrowhead – contains what just might be a medieval female warrior.

A new archeological analysis by University of Szeged bioarchaeologist Balázs Tihanyi and colleagues genetically confirmed the sex of the individual found in a medieval cemetery in eastern Hungary, which along with the grave goods, morphological evidence of an active lifestyle, and signs of injury, raised questions on the role women may have played in combat in medieval Europe.

The existence of medieval female warriors through history often attracts heated debate. For one thing, weapons found in graves may not have been used by the grave's occupant. What's more, claims of a warrior's sex are often based on morphological indicators, are which is far less reliable than DNA evidence.

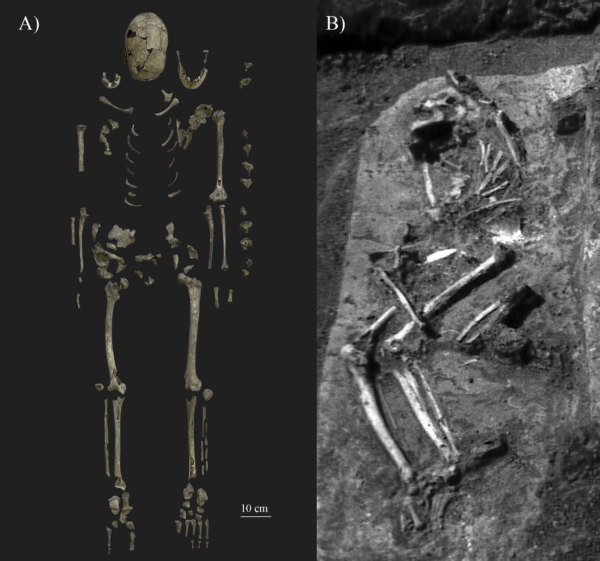

Grave 63 in the east-Hungarian cemetary of Sárrétudvari–Hízóföld was among 262 burials left by the Hungarian conquest of central Europe in the 10th century CE. Within the grave was the skeleton of one individual lying on their right side, along with a string of colorful beads, a hair ring, buttons, an antler bow plate, arrowheads, and fragmented iron parts of a quiver.

As Tihanyi explained to Sandee Oster at Phys.org, men in medieval European cultures were typically buried with functional items like tools and knives, or occasionally practical clothing accessories such as belt buckles, hair rings, and bracelets. Notable among Sárrétudvari–Hízóföld's men's graves were archery equipment and occasional weapons, including two with sabers and one with an axe.

"Female burials, in contrast, more frequently contained jewelry (e.g. hair rings, braid ornaments, bead necklaces, bracelets, and finger rings) and clothing fittings (e.g. bell buttons and metal ornaments). Tools, such as knives and awls, appeared less often," Tihanyi told Oster.

"The grave goods found in the burial of [Sárrétudvari–Hízóföld]-63 contained a mix of these characteristics. Compared to other graves in the cemetery, its inventory was relatively simple, including common jewelry and clothing fittings."

Unfortunately the skeleton in grave 63 was in such poor condition, with little facial structure remaining, that the team couldn't establish a clear estimate of the person's age or general health condition prior to death. But investigation of the joint bones revealed morphological changes, mostly on the woman's right side, consistent with those seen in other skeletons found with weapons or horse-riding equipment.

Tihanyi and his team also identified signs of osteoporosis, suggestive of a woman in her later life, as well as three major trauma injuries that hadn't fully healed. These also hint at a physically active existence.

Given the available archeological materials, the researchers caution they can't yet confirm if the woman ought to be considered as a warrior, a term that describes individuals of a particular social class.

What's more, other contemporary societies trained girls to use weapons for protection of themselves and livestock, rather than for battle, so this scenario can't be ruled out either.

"No written data are available concerning warrior women among the Magyars in the 10th century CE," Tihanyi and team point out.

"Nevertheless, we can confidently conclude that this individual indeed represents the first known female burial with weapons from the Hungarian Conquest period in the Carpathian Basin," they conclude.

This research was published in PLOS One.