Black holes don't just sit there munching away constantly on the space around them. Eventually they run out of nearby matter and go quiet, lying in wait until a stray bit of gas passes by.

Then a black hole devours again, belching out a giant jet of particles. And earlier this year scientists announced they'd captured one doing so not once, but twice - the first time this had been observed.

The two burps, occurring within the span of 100,000 years, confirm that supermassive black holes go through cycles of hibernation and activity.

It's actually not as animalistic as all that, since black holes aren't living or sentient, but it's a decent-enough metaphor for the way black holes devour material, drawing it in with their tremendous gravity.

But even though we're used to thinking how nothing ever comes back out of a black hole, the curious thing is that they don't retain everything they capture.

When they consume matter such as gas or stars, they also generate a powerful outflow of high-energy particles from close to the event horizon, but not beyond the point of no return.

"Black holes are voracious eaters, but it also turns out they don't have very good table manners," said lead researcher Julie Comerford, an astronomer at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"We know a lot of examples of black holes with single burps emanating out, but we discovered a galaxy with a supermassive black hole that has not one but two burps."

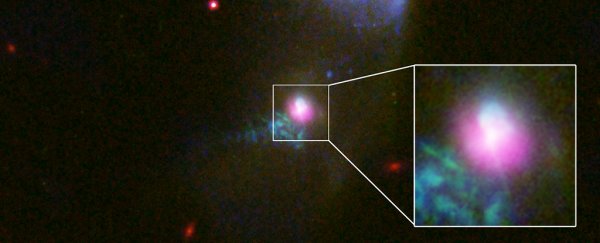

The black hole in question is the supermassive beast at the centre of a galaxy called SDSS J1354+1327 or just J1354 for short. It's about 800 million light-years from Earth, and it showed up in Chandra data as a very bright point of X-ray emission - bright enough to be millions or even billions of times more massive than our Sun.

The team of researchers compared X-ray data from the Chandra X-ray observatory to visible-light images from the Hubble Space Telescope, and found that the black hole is surrounded by a thick cloud of dust and gas.

"We are seeing this object feast, burp, and nap, and then feast and burp once again, which theory had predicted," Comerford said. "Fortunately, we happened to observe this galaxy at a time when we could clearly see evidence for both events."

That evidence consists of two bubbles in the gas - one above and one below the black hole, expulsions particles following a meal. And they were able to gauge that the two bubbles had occurred at different times.

The southern bubble had expanded 30,000 light-years from the galactic centre, while the northern bubble had expanded just 3,000 light-years from the galactic centre. These are known as Fermi bubbles, and they are usually seen after a black hole feeding event.

From the movement speed of these bubbles, the team was able to work out they occurred roughly 100,000 years apart.

So what's the black hole eating that's giving it such epic indigestion? Another galaxy.

A companion galaxy is connected to J1354 by streams of stars and gas, due to a collision between the two. It is clumps of material from this second galaxy that swirled towards the black hole and got eaten up.

"This galaxy really caught us off guard," said doctoral student Rebecca Nevin.

"We were able to show that the gas from the northern part of the galaxy was consistent with an advancing edge of a shock wave, and the gas from the south was consistent with an older outflow from the black hole."

The Milky Way also has Fermi bubbles following a feeding event by Sagittarius A*, the black hole in its centre. And, just as J1354's black hole fed, slept, then fed again, astronomers believe Sagittarius A* will wake to feed again too.

The research was presented at the 231st meeting of the American Astronomical Society, and has also been published in The Astrophysical Journal.

A version of this article was first published in February 2018.