The United States is experiencing its first cases of 'sloth fever' after 21 travelers returned from Cuba infected with the oropouche (pronounced or-oh-poosh) virus earlier in August.

Officials at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that most of these patients have fully recovered from the insect-borne disease, although three are experiencing recurrent symptoms.

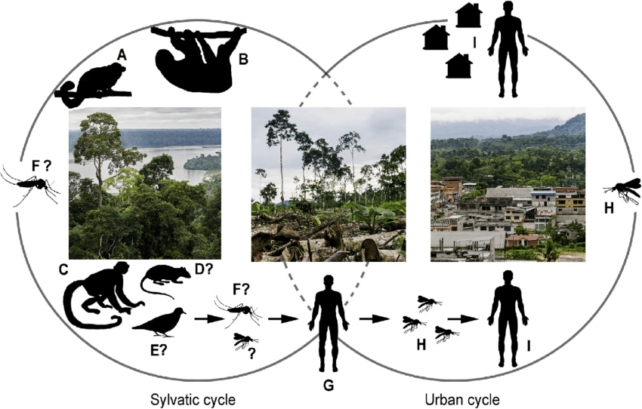

To date, there is no evidence that the oropouche virus can jump from human to human. The pathogen is thought to develop in some tropical insects of Central and South America, which then infect forest animals – principally sloths, but also some primates, rodents, and birds.

The risk of local transmission in the US is deemed low, however the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) recently put out an advisory warning urging member states to strengthen their surveillance of the disease, as cases in Central and South America and the Caribbean surge for unknown reasons.

Officials at PAHO say they are highly concerned by the oropouche virus spreading into regions where it was not previously considered endemic, such as Bolivia and Cuba. Public health experts suspect factors like climate change, deforestation, and unplanned urbanization are facilitating disease spread.

There are currently no medicines that can treat or prevent the ongoing outbreak. As of July, the World Health Organization has reported more than 8,000 cases, spread across Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, and Peru.

The oropouche virus is spread by at least two insects – a mosquito and a midge – and it was first observed in a three-toed sloth, hence its colloquial name. In humans, the viral infection is easily mistaken for dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika, or malaria. Symptoms include a sudden fever, a severe headache, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, chills, muscle aches, or joint pain. In rare cases, the disease can prove fatal.

Twenty of the travelers who returned to the US with sloth fever were identified by the Florida Department of Health (FLDOH), after the entire group tested negative for dengue. The travelers had just visited Cuba, where the oropouche virus has been circulating since June.

The other case of sloth fever was identified in a traveler who returned to the state of New York from Cuba.

"Oropouche and dengue viruses can co-circulate and cause similar symptoms" explain officials at the CDC; "patients with clinically suspected dengue should be managed according to dengue clinical management recommendations until dengue is ruled out."

European health officials recently issued similar guidance after 19 cases of sloth fever were detected in travelers returning from South America.

This isn't the first time an outbreak of oropouche virus has struck South and Central America. Since the virus was first detected in the Caribbean in 1955, roughly half a million people have been infected, bitten by the midge species Culicoides paraensis or a type of mosquito called Culex quinquefasciatus, both of which are found in tropical regions.

Nevertheless, this is the first time that human deaths have ever been attributed to the virus. Sloth fever has so far claimed the lives of a 21-year-old woman and a 24-year-old woman in Brazil.

Experts fear the oropouche pathogen is also having a fatal impact on fetuses in a similar way to the Zika virus. Antibodies against oropouche were recently found in newborns in South America with microcephaly, a congenital condition that severely impacts brain development.

"Acknowledging that these observations are still in the initial stages of investigation and the true trajectory is unknown, the risk level for the region has been upgraded to high," PAHO warned on 3 August 2024.

Whether the pathogen can be spread by insects found in other regions is currently unknown. A recent study, however, found evidence that a species of midge in the US and Canada can also transmit oropouche if it becomes infected.

This could be a route by which the disease starts to spread on a new continent.

The CDC says they are working with partners like PAHO to better understand how this disease is spilling over to humans, and why there is a current outbreak. The potential risks that can occur during pregnancy have officials warning that pregnant people should defer travel to areas experiencing outbreaks.

Protection from mosquito bites while traveling in these areas is a must.