A lonely black hole roaming the cosmos in solitude has been confirmed for the first time. A closer look has revealed the dark object's identity, after much hubbub.

The new analysis shows that the black hole has a mass of around 7.15 times that of the Sun, it's about 4,958 light-years away, and it's shooting through space at a speed of around 51 kilometers (32 miles) per second.

But what's really special about it is that it's the only verified solitary black hole discovered wandering the Universe. Others of this class are usually found to have companions. In our galaxy, that's mostly stars, and it's the weird wobbles in those far-more-visible friends that give away the black hole's presence.

Farther afield, pairs of black holes have also been detected through the gravitational waves they emit as they orbit each other and merge.

Without a buddy, this black hole made itself known through a different mechanism, called gravitational microlensing. Essentially, its intense gravity warped the light from a background star, amplifying it and temporarily changing its apparent position in the sky.

The calculated mass of the lens, as well as the lack of any emitted light of its own, indicates a black hole. The path to its identification wasn't as smooth as it sounds, however.

The object first appeared in data in 2011, from two separate surveys searching for exactly this kind of event: the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) and Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA).

The Hubble Space Telescope followed up with eight observations over six years, to determine how warped that starlight was. Photometry data was collected from 16 different telescopes and spectroscopy observations were taken at the peak of amplification.

All together, this data pointed to a solo black hole of about 7.1 solar masses, located about 5,153 light-years away.

But a second analysis conducted in 2022, using more Hubble data, came to a different conclusion. This team refined the mass estimate to between 1.6 and 4.4 solar masses. Since that's generally too small to be a black hole, they proposed a neutron star was a more likely candidate.

However, a series of follow-up studies, including another from the neutron star team, lend more weight to the black hole explanation.

Now, a new analysis, involving many of the scientists from the original study, unambiguously confirms that identity. It includes an extra three Hubble observations, extending the timeframe to 11 years, as well as updated OGLE data.

"Our revised analysis, with the additional Hubble observations and updated photometry included, leads to results that have higher accuracy but are consistent with our previous measurements and our conclusion that the lens is a stellar-mass black hole," the team writes in a new paper.

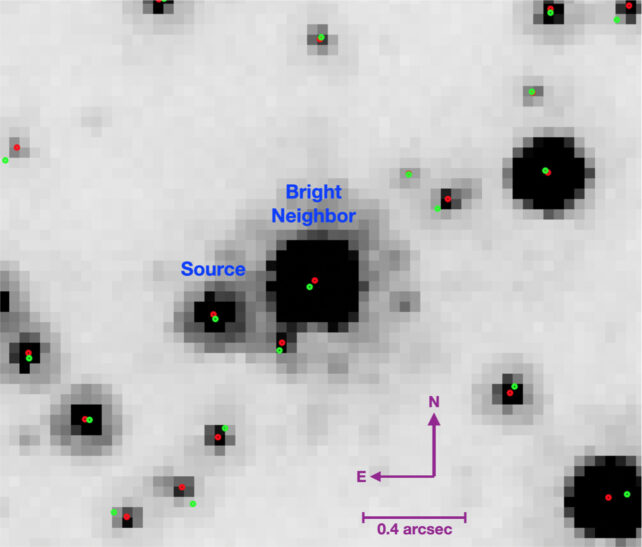

One of the biggest challenges in observing the lens is that the light from the background star is washed out by a very bright neighbor. The scientists had to very carefully subtract that light for each observation, as well as account for variations caused by different thermal environments in each Hubble orbit.

The team also searched for any signs of a companion, and found that there's nothing bigger than 0.2 solar masses within at least 2,000 times the distance between Earth and the Sun.

This may be the first black hole confirmed to be going solo, but it's far from the only one. The Universe should be teeming with these invisible rogues – it's just extremely rare that one would make itself known to us.

The research was published in The Astrophysical Journal.