New research highlights the stark choice we face when it comes to climate change: solve the crisis now, or spend a lot more money and resources solving the crisis in the future, after environmental tipping points have been passed.

A team from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) and Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) crunched the necessary numbers, using multiple variations on a climate model and the scenario of sea ice loss.

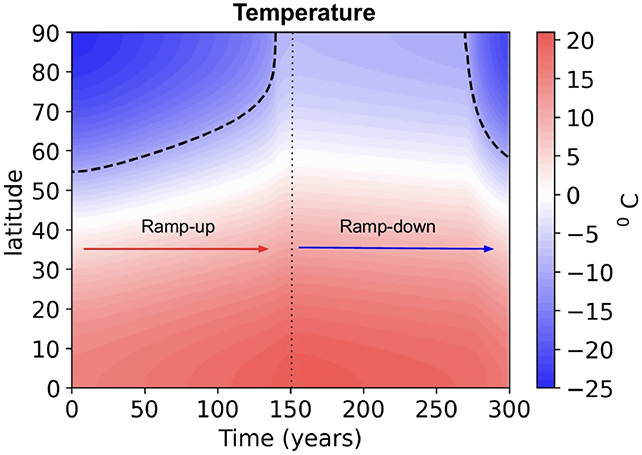

Tipping points refer to thresholds beyond which widespread, significant change becomes inevitable, even if the drivers of that change are removed. In this case, researchers considered when ice-free polar regions would become inevitable, even if we were to somehow stop global warming.

"You either shoulder the cost now, just before the threshold is crossed, or you wait," says mathematician Parvathi Kooloth, from the PNNL.

"And if you wait, the degree of intervention needed to bring the climate system back to where it was rises steeply."

It makes sense that the longer climate change continues, the more it will take to reverse course. But here, the researchers wanted to specifically quantify the increased cost post-tipping point, using their sea loss ice scenario.

In this case, a fourfold increase happens quickly after the tipping point is reached, the team found.

While the models showed the steep rise in costs can be delayed – potentially giving us more time to reverse course and fully restore an ecosystem – once that 'overshoot window' passes, the cost of reversal goes up even faster.

Not all of the consequences of tipping points can be reversed, warn the researchers. And while tipping points can be quickly passed, undoing the damage and going back in the other direction usually takes much more time and effort.

"If we arrive in the year 2100 with no sea ice, it may not be sufficient to bring the ice back if we dialed our emissions down to the levels we're emitting now in 2024, when we still have some ice left," says Kooloth.

"We may need to dial emissions down much further, to levels predating 2024 – that asymmetry is important for us to consider as we choose our path forward."

While every tipping point is unique – and a mix of many different factors and influences – the researchers suggest they all share fundamental principles. The team is confident the findings here about sea ice can be compared to other scenarios too, from dying coral reefs to disappearing rainforests.

There is some positive news here, too. Studies like this have the potential to help us better identify and predict tipping points as they approach. In theory, that should help us avoid them – though as a species our record isn't great at heeding the warnings of scientists.

"We know a great deal about the climate system today," says Kooloth. "But even now we're never really sure how far or close we are to a tipping point."

"Could we one day use observable precursors to provide early warning? My hope is that we can."

The research has been published in npj Climate and Atmospheric Science.