'Flesh-eating' bacteria have been found thriving on seaweed blooms and plastic pollution in the open Caribbean Ocean, and researchers worry the potential pathogens could come back to bite us.

Vibrio bacteria are known to feast on marine plant and animal tissues on the coastline. When humans consume seafood or seawater infected with these pathogens, they can cause life-threatening illnesses like cholera. The species Vibrio vulnificus can even infect wounds, risking life-threatening destruction of surrounding tissue.

Finding a number of Vibrio species, some of which are undescribed, happily living their best life on waste is far from good news. It's yet another potential vector for human disease that experts have not accounted for. Even worse, the floating habitat isn't going anywhere. In fact, it seems to be expanding in size and washing up on our coastlines like never before.

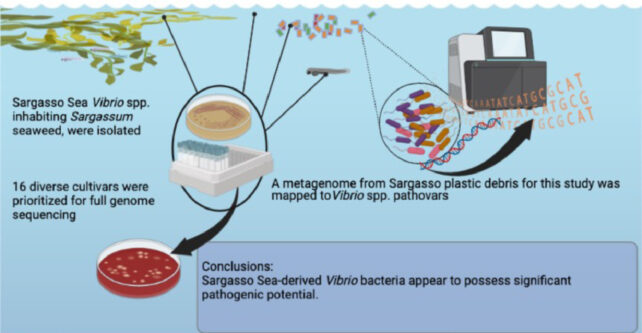

The recent analysis from Florida Atlantic University included samples of ocean plastic collected in the Caribbean and Sargasso Seas in 2012 and 2013, as well as samples of brown seaweed, called Sargassum, eel larvae, and seawater.

In both the plastic and seaweed samples, the team found multiple species of Vibrio bacteria, some of which have never been seen before.

Further genome analysis suggested that some had "significant pathogenic potential".

In experiments in the lab, the open-ocean bacteria clung to and colonized plastic samples with alarming efficiency.

"Our lab work showed that these Vibrio are extremely aggressive and can seek out and stick to plastic within minutes," says marine biologist Tracy Mincer from Florida Atlantic University.

"We also found that there are attachment factors that microbes use to stick to plastics, and it is the same kind of mechanism that pathogens use."

Previous studies have suggested that Vibrio pathogens are early colonizers of floating marine plastic, but Mincer and his colleagues at FAU are the first to sequence their genomes from a real-world sample.

The results suggest that Vibrio bacteria might be adapting to life on the open ocean in ways that could be dangerous to animal and human health. Some of the pathogens out in the blue might even be evolving toxic secretions, which can penetrate an animal's intestine to cause leaky gut syndrome.

"For instance," explains Mincer, "if a fish eats a piece of plastic and gets infected by this Vibrio, which then results in a leaky gut and diarrhea, it's going to release waste nutrients such nitrogen and phosphate that could stimulate Sargassum growth and other surrounding organisms."

Thanks to the widespread use of fertilizers, Sargassum seaweed in the Caribbean has begun to bloom in greater swathes than ever before, suffocating great stretches of beach in the process.

As a solution, some experts think we should convert the abundance to food or biofuel.

Until the risks are explored further, researchers warn we should hold off on harvesting the world's largest bloom of seaweed, as some have suggested.

As floating seaweed and plastic debris meet and mix in the ocean like never before, they could tangle up and trade microbes, leading to potentially dangerous health outcomes when they wash up on the beach.

Until we know the risks, researchers warn that Sargassum seaweed should not be touched.

"I don't think at this point, anyone has really considered these microbes and their capability to cause infections," says Mincer.

"We really want to make the public aware of these associated risks."

The study was published in Water Research.