Spending time in space has all sorts of effects on astronauts. Some perils of spaceflight are serious, others are best described as weird, and some fall in between, like the fact that food tastes bland and unappealing in space.

This curious phenomenon can be a serious enough problem that some astronauts struggle to receive sufficient nutrition, leading a team of food scientists from Australia and the Netherlands to look into potential causes.

Their recently published new study suggests that the explanation may lie in astronauts being isolated and uncomfortable, rather than being in orbit.

Previous research has suggested the issue might result from fluid shifts, an effect of weightlessness on how the body's internal fluids are distributed, causing facial swelling that recedes as the body acclimatizes to its new environment.

However, some astronauts have reported that their problems with food have persisted even after the effects of fluid shift have passed.

So food scientist Grace Loke from RMIT University in Australia and her colleagues focused on how a person's surroundings and mental state can affect their perception of aromas, which are highly influential on the perceived appeal of food.

The results suggest that at least some aromas are perceived differently in different environments – albeit not in the way that researchers expected.

"One of the long-term aims of the research is to make better-tailored foods for astronauts, as well as other people who are in isolated environments, to increase their nutritional intake closer to 100 percent," says senior author Julia Low, a sensory and eating behavior scientist at RMIT.

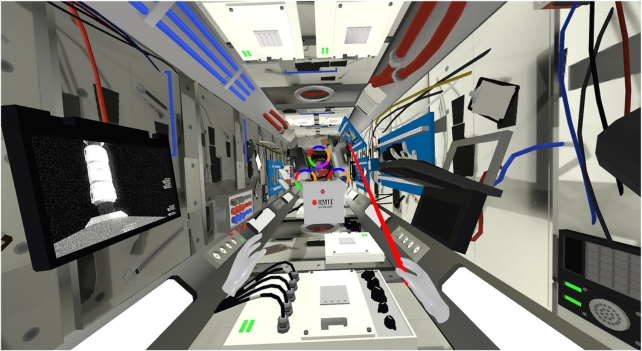

Given the obvious difficulty of actually sending their subjects to space, the team instead placed participants in a virtual reality environment designed to simulate the experience of being on the International Space Station (ISS).

This VR environment included floating objects to simulate microgravity, the team explains, along with "mounted space apparatus to evoke a sense of clutter and confinement" and background noise that "imitate[d] loud operational sounds that have been reported within the ISS".

While the idea that taste is subjective is certainly not new, the question of whether a VR environment can influence taste appears to be – Loke and her team note in their paper that, to their knowledge, "This is the first study to demonstrate individual variation in olfactory perception in VR".

To do this, the scientists provided participants with samples of three different odors: vanilla, almond, and lemon. They were asked to rate each scent's intensity on a scale of 1 to 5 – first in a normal room and then in the simulated ISS environment.

Fascinatingly, participants reported that while the lemon smell remained the same in both environments, the other two scents seemed more intense in the simulated ISS. The researchers suspect that benzaldehyde, a volatile aromatic compound found in both almonds and vanilla but not lemon, is the key factor in this.

And while the study doesn't necessarily provide answers about why astronauts' senses of taste and smell remain dulled after fluid shift abates, it does provide support for the hypothesis that perception of odor is contextual.

It also points at possible ways of mitigating the issue: as the authors write, "Perhaps certain volatile compounds sharing common odor profiles (i.e. sweet) are more likely to be contextually affected compared to others".

If this is the case, identifying compounds that retain their appeal in environments like the ISS – or even become more appealing – could inform the way astronauts' diets are designed.

There are potential uses for the findings back on Earth, too.

"This study could help personalize people's diets in socially isolated situations, including in nursing homes, and improve their nutritional intake," Low says.

The paper is published in the International Journal of Food Science + Technology.