A world just over 300 light-years away has yielded the first ever detection of isotopes in an exoplanet's atmosphere.

In the haze around a gaseous exoplanet named TYC 8998-760-1 b, astronomers detected a form of carbon known as carbon-13. This discovery suggests that the exoplanet formed far from its parent star, in the cold reaches of its system beyond a specific snow line.

According to the researchers, the discovery gives us a new way to look into the poorly understood process of planet formation.

"It is really quite special that we can measure this in an exoplanet atmosphere, at such a large distance," said astronomer Yapeng Zhang of Leiden University in the Netherlands.

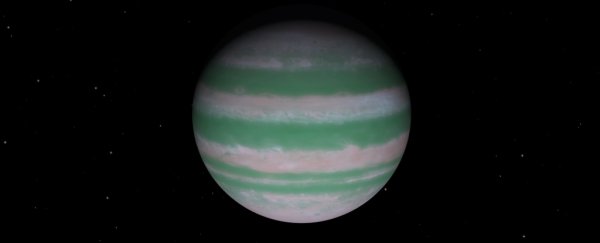

TYC 8998-760-1 b, discovered in 2019, was already pretty special. It belongs to an extremely rare group of exoplanets - those we have been able to image directly.

Stars are very, very bright, and planets very dim by comparison, so usually we identify them by detecting the effect they have on their host star, either gravitationally, or by minutely dimming the star's light as they pass in front.

These techniques work best for planets that are close to their stars, but TYC 8998-760-1 b orbits its star at quite a distance - around 160 astronomical units. Pluto, for context, orbits the Sun at a distance of 40 astronomical units.

The exoplanet is also a chonk, clocking in at around 14 times the mass and twice the size of Jupiter, which means it's relatively bright with reflected starlight. So a team of researchers led by Zhang took a closer look to see if the light reflected by the star could tell them anything.

Specifically, they used an instrument called the Spectrograph for Integral Field Observations in the Near Infrared (SINFONI) on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile. This instrument observes a spectrum of light; the team were looking for absorption features.

These are dark lines in a spectrum that occur when certain wavelengths of light are absorbed by certain elements. The researchers found that the wavelengths absorbed by TYC 8998-760-1 b are consistent with carbon-13, likely primarily bound up in carbon monoxide gas.

Isotopes are pretty interesting. They are all forms of the same element that have the same number of protons and electrons, but differing numbers of neutrons.

Carbon-12, the most common stable carbon isotope, has six of each. Carbon-13 has six protons and six electrons, but seven neutrons. This matters because their formation pathways are different, and they behave differently depending on their environmental conditions.

On TYC 8998-760-1 b, the researchers were expecting a certain abundance of carbon. The amount of carbon-13 they found in the exoplanet's atmosphere was twice this expected abundance. The team believes that this can tell us something about the conditions under which TYC 8998-760-1 b formed.

"The planet is more than one hundred and fifty times farther away from its parent star than our Earth is from our Sun," explained astrophysicist Paul Mollière of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany.

"At such a great distance, ices have possibly formed with more carbon-13, causing the higher fraction of this isotope in the planet's atmosphere today."

This region would be out beyond the carbon monoxide snow line - the distance from the star beyond which carbon monoxide condenses and freezes from gas into ice (different gases have different snow lines).

Any exoplanets forming that far from the warmth of the star would incorporate these carbon monoxide ices. Since the known planets in the Solar System are closer than this distance from the Sun, they would not form with as much carbon monoxide as TYC 8998-760-1 b, the researchers posited.

We have an analogous phenomenon here in the Solar System, whereby Neptune and Uranus are richer in deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen with one proton and one neutron (normal hydrogen only has a proton), than Jupiter. This is attributed to planet formation past the water snow line.

The detection of isotopes in atmospheres is not going to be possible yet for many exoplanets, but as our telescopes keep improving, it could provide a new means for studying exoplanet formation, the researchers said.

"The expectation is that in the future, isotopes will further help to understand exactly how, where and when planets form," said astronomer Ignas Snellen of Leiden University. "This result is just the beginning."

The research has been published in Nature.