For the first time, astronomers have obtained high-resolution images of a binary star system in the early stages of formation, and it's more beautiful than we ever expected.

Here on Earth, we're used to orbiting a lone star. But out there in the wider Universe, most stars come with their own little star families, or stellar systems, where two or more stars are gravitationally bound to each other.

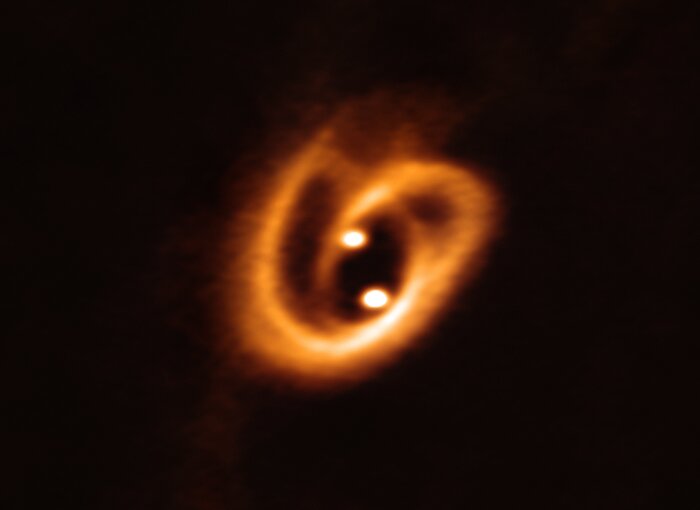

The [BHB2007] 11 binary shown in these latest images is located at least 600 light-years away from us in the Pipe Nebula, a dark cloud of interstellar dust and gas that's given rise to an entire cluster of stars, including this baby binary.

(ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), Alves et al.)

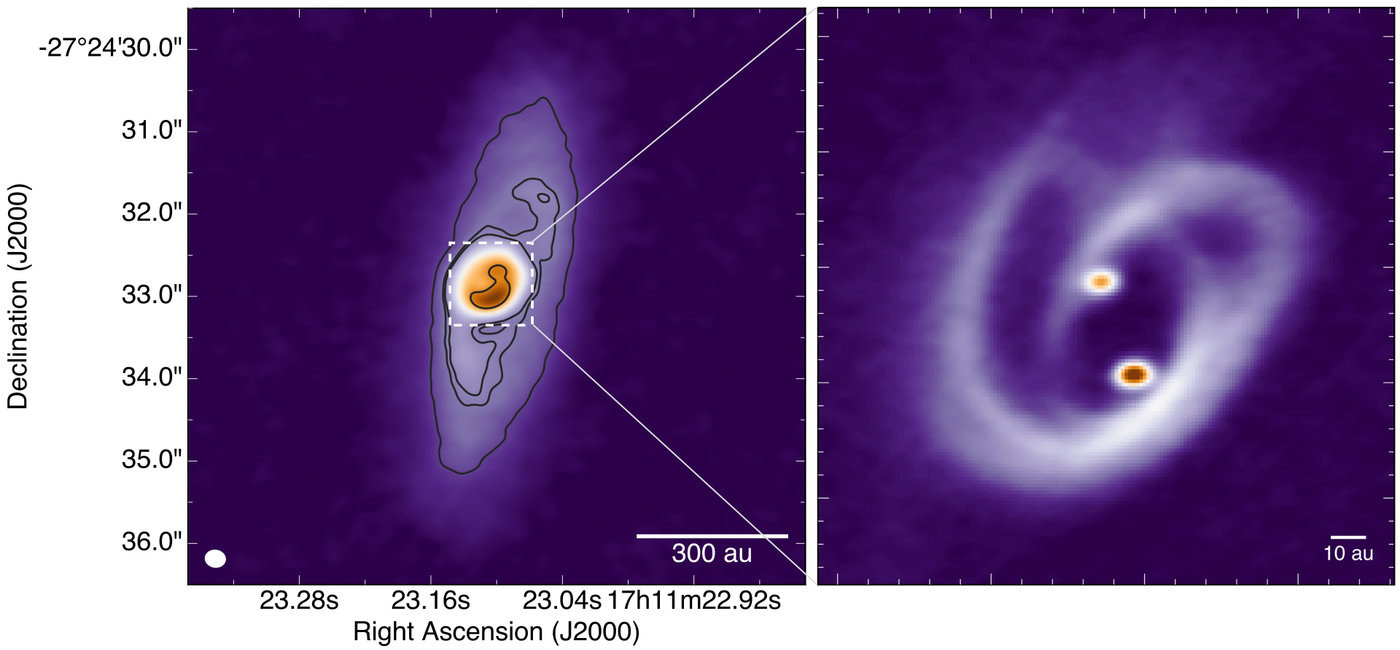

(ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), Alves et al.)

When stars are being born, they are enveloped by a swirl of matter known as the circumstellar disk. Throw more than one star into the mix, and the shape of that disk is bound to get complicated, as mass moves from the surrounding material and falls into the young stars.

Astronomers had already seen the rough outline of the puzzling structures surrounding [BHB2007] 11, but this latest discovery allowed them to peer within, revealing the intricate network of gas and dust filaments dancing around the two bright dots.

A zoom into the circum-binary disk of [BHB2007] 11 observed with ALMA. (MPE)

A zoom into the circum-binary disk of [BHB2007] 11 observed with ALMA. (MPE)

To attain such high-resolution data, the international team of astronomers led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) in Germany used ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array), the massive array of 66 antennas located in Chile.

Not only does each star have its own circumstellar disk, but the pair is also surrounded by a circum-binary disk that's slowly but surely being accreted into their respective disks through an intricate network of dust filaments.

The team estimates that material falls into the binary at a rate of about 0.01 Jupiter masses per year, although one of the stars is more massive, and is therefore slurping up material from its disk at a higher rate - you can see this as the brighter area towards the bottom of the image above.

"We have finally imaged the complex structure of young binary stars, with their 'feeding filaments' connecting them to the circum-binary disk. This provides important constraints for current models of star formation," says MPE astronomer Paola Caselli.

The researchers were excited to find that these observations neatly agree with our theoretical understanding of how binary star systems are born, although they note we'll need to study many more young binaries to be sure. Bring on the pics, we say.

The research has been published in Science.