Just a few fossil fragments of a tiny creature discovered thousands of miles north of its contemporaries have shaken our understanding of global dinosaur history.

"It was basically the size of a chicken but with a really long tail," says lead author Dave Lovelace, a vertebrate paleontologist from the University of Wisconsin Geology Museum. "We think of dinosaurs as these giant behemoths, but they didn't start out that way."

With a recent radioisotopic analysis of the fossil specimens dating the remains to around 230 million years old, this tiny 'terrible lizard' named Ahvaytum bahndooiveche is now the oldest-known dinosaur from Laurasia, the Northern Hemisphere land mass of the late Paleozoic supercontinent Pangea.

That age places it in a similar time period to dinosaurs of Pangea's Southern Hemisphere land mass, Gondwana, which were thought to be the world's first by a long shot.

"Nearly 6–10 million years separates Gondwanan faunas and the oldest known dinosaur occurrence in the Northern Hemisphere," the authors write in their paper announcing the find.

Discovered in 2013 in modern-day Wyoming, the A. bahndooiveche fragments are now evidence the mainstream view of dinosaurs being confined to Gondwana for millions of years before spreading into Laurasia needs revising.

"Our understanding of dinosaur origins is biased by an apparent absence of Carnian-aged (237–227 million years ago) Laurasian terrestrial strata," the authors write.

"This [discovery] suggests a relatively cosmopolitan distribution of dinosauromorphs throughout the mid-late Carnian, rather than a delayed equatorial and northern hemisphere dispersal as previously thought."

This period of time is known for major climate shifts that made the whole planet significantly wetter and warmer, turning inhospitable deserts into habitat, and providing the raw materials for a boom in the diversity of life forms.

Inhospitable climate barriers are thought to be the main reason for a lack of theropod and sauropod fossils from this time period, but the team suggests this absence may have more to do with environmental conditions making the preservation of body fossils uncommon, with the A. bahndooiveche specimens a rare exception.

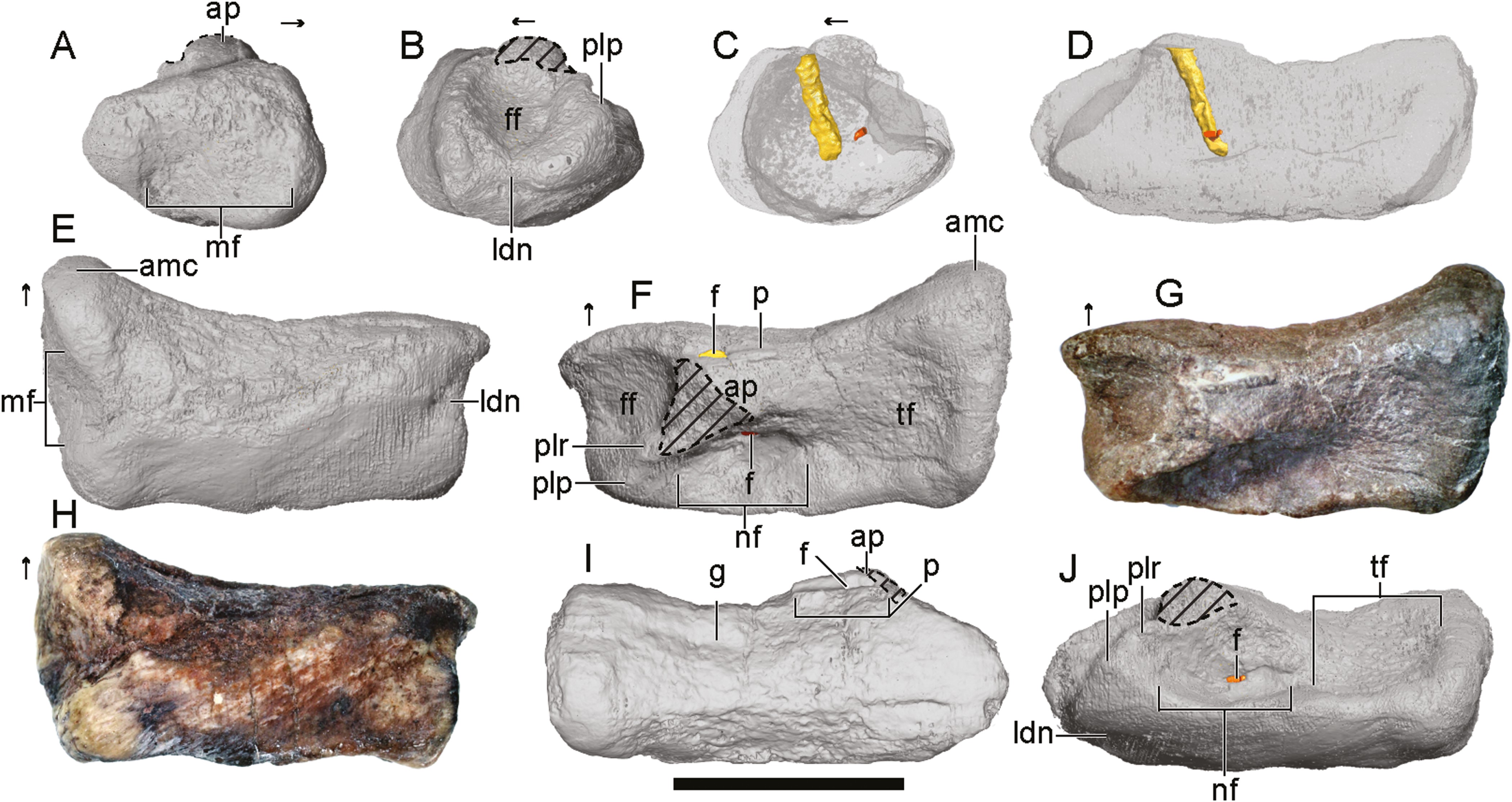

Most of the fossils used in this research were from the species' legs – the team found no complete specimens, but that's pretty typical for fossils this old.

Nonetheless, they were able to identify the species as sauropod-like. The better-known members of this clade are Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus, plant-eating dinosaurs that would have towered over little A. bahndooiveche if not for the millions of years separating them.

And a dinosaur-like footprint in much older rocks at the site hints that dinosaurs or their cousins may have even inhabited the region a few million years before the Ahvaytum specimens.

Members of the Eastern Shoshone Tribe, whose ancestral lands include the site where these fossils were found, were involved in conducting the field work and in choosing the species' name, which translates broadly to 'long ago dinosaur' in the Shoshone language.

"Typically, the research process in communities, especially Indigenous communities, has been one sided, with the researchers fully benefiting from studies," says co-author and educator Amanda LeClair-Diaz, a member of the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes.

"The work we have done with Dr Lovelace breaks this cycle and creates an opportunity for reciprocity in the research process."

This research was published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.