Global carbon dioxide emissions are projected to rise again in 2017, climate scientists reported Monday, a troubling development for the environment and a major disappointment for those who had hoped emissions of the climate change-causing gas had at last peaked.

The emissions from fossil fuel burning and industrial uses are projected to rise by up to 2 percent in 2017, as well as to rise again in 2018, the scientists told a group of international officials gathered for a United Nations climate conference in Bonn, Germany.

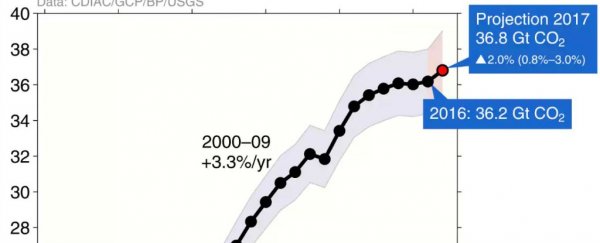

Despite global economic growth, total emissions held level from 2014 to 2016 at about 36 billion tons per year, stoking hope among many climate change advocates that emissions had reached an all-time high point and would subsequently begin to decline.

But that was not to be, the new analysis suggests.

"The temporary hiatus appears to have ended in 2017," wrote Stanford University's Rob Jackson, who along with colleagues at the Global Carbon Project tracked 2017 emissions to date and projected them forward.

"Economic projections suggest further emissions growth in 2018 is likely."

The renewed rise is a troubling development for the global effort to keep atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases below the levels needed to mitigate the worst effects of climate change.

The more we emit now, scientists say, the more severe cuts will have to be later. That's because of the very long atmospheric lifetime of carbon dioxide, which means we can only emit a fixed amount in total if we want to stay within key climate goals.

(Global Carbon Project)

(Global Carbon Project)

"It's sort of, lose one year now, you have to pick up five years later," said Glen Peters, one of the study's co-authors and a researcher at the Center for International Climate Research in Oslo.

Emissions are forecast to reach around 37 billion tons of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel burning and industrial activity in 2017, said the group, which published the results in the journal Environmental Research Letters and more detailed findings in Earth System Science Data Discussions.

The renewed increase is driven largely by more fossil fuel burning in China and many other nations.

"We've been lucky in the last three years with emissions being flat without any real policy driving it," Peters said. "If we want to ensure that emissions remain flat we have to put policies in place . . . and the second step is to start to drive emissions down."

Peters said the 2017 number would be a record high for emissions from fossil fuel burning and industrial uses (such as cement), although carbon emissions from deforestation and land-use changes were actually higher in 2015.

The scientists also acknowledge some uncertainty in their estimate, meaning that the 2017 emissions rise could be as low as 1 percent or as high as 3 percent.

ROW stands for Rest of the World (Jackson et al, Environmental Research Letters, 2017.)

ROW stands for Rest of the World (Jackson et al, Environmental Research Letters, 2017.)

All in all, the finding is bad news for global climate policy.

The Paris agreement, now supported by every nation except for the United States, aims to limit the warming of the planet to "well below" 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels, and to try to hold warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

But this requires emissions not just to stay flat but to go down - rapidly.

"The 2017 emissions data make it crystal clear that urgent and very serious emissions reductions are needed to stop global warming below 2° C, as was unanimously agreed in Paris," Stefan Rahmstorf, a climate scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, said in an email.

Rahmstorf was not involved with the current work.

Rahmstorf said there are currently about 600 billion remaining tons of carbon dioxide that can be emitted if the world is to have a good chance of keeping warming considerably below 2 degrees Celsius, and with some 40 billion tons of emissions each year, that leaves just 15 years.

"If we start to ramp down emissions from now on we can stretch this budget to last us about 30 years," he said. "With every year that we wait we will have to stop using fossil energy even earlier."

The rise of global emissions projected for the year 2017 in the current research is attributable to multiple causes.

In particular, China's emissions were projected to increase by 3.5 percent in 2017 as the country consumed more of all three of the top fossil fuels - coal, natural gas and oil. China is the single largest emitting country.

India, which has been experiencing rapid emissions growth, will pull back to 2 percent growth in 2017 because of economic contraction, the research suggests.

Emissions from the United States and European Union are projected to decline 0.4 percent and 0.2 percent, respectively. But emissions for the rest of the globe – which, in total, are even larger than China's – will rise by close to 2 percent, according to the projection.

If the increase continues, what many hoped was a plateau in emissions seen from 2014 to 2016 could come to look more like a pause.

During that era, many cited a broad "decoupling" of economic growth and emissions growth, thanks in part to greater energy efficiency and renewable energy.

And there's no denying that renewables are continuing to grow around the world – making it hard to know quite what to make of the current emissions rise.

"It's too early to say whether it's a long-term trend, or just a one-off little blip," Peters said.

The new results reinforce just how much of the globe's emissions trajectory depends on China, its largest emitter.

China took a number of steps to cut back coal emissions in the past three years, notes Joanna Lewis, a Georgetown University professor who studies energy trends in the country. This led to less coal use in the electricity and industrial sectors.

"What is less clear is whether these trends can continue," Lewis said by email.

"Reduced plant operation and closures around the country are putting huge pressures on local governments to deal with slowing economic growth and unemployment.

Overcapacity in these sectors, and particularly an overbuild of coal plants, means there is pressure to increase coal electricity production, which is often done through the curtailment of renewables. As a result, China's long term CO2 emissions trends are unclear at best."

While 37 billion tons of carbon dioxide from fossil fuels and industry represent the lion's share of the globe's emissions, there are also several billion tons of carbon dioxide each year from deforestation and other changes in how humans use land.

When it comes to global tree loss, there are also worrying signs that it is not abating as hoped.

There are also rising emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas that is a stronger and faster warming agent, although not nearly as long-lived in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

There is still a debate over where the methane growth is coming from, but much of it could be from animal agriculture.

The new findings will be immediately relevant to the proceedings in Bonn, since one part of the agenda involves laying the groundwork for a "facilitative dialogue" to take place next year, in which countries will take a hard look at where their emissions are, and where they need to be, to live up to the Paris goals.

Higher emissions will, in this context, inevitably mean deeper cuts will be required of participating nations - even as deadlines for avoiding the most severe effects of global warming draw near.

2017 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.