For roughly 250 million years, some 20,000-odd species of trilobite scuttled across Earth's ocean floor. Despite the huge abundance these diverse animals in our fossil records, much of their basic biology is still unclear, like what they ate.

Until now, trilobite diets have only been inferred from indirect clues, but researchers have just discovered the first trilobite specimen that still has signs of its final meals frozen in time within.

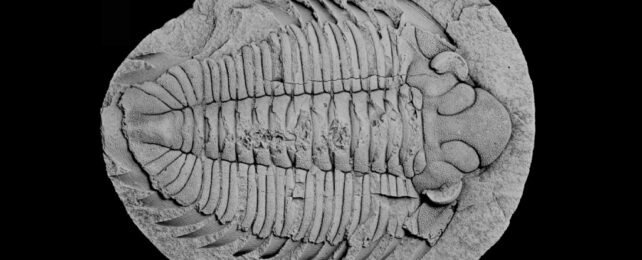

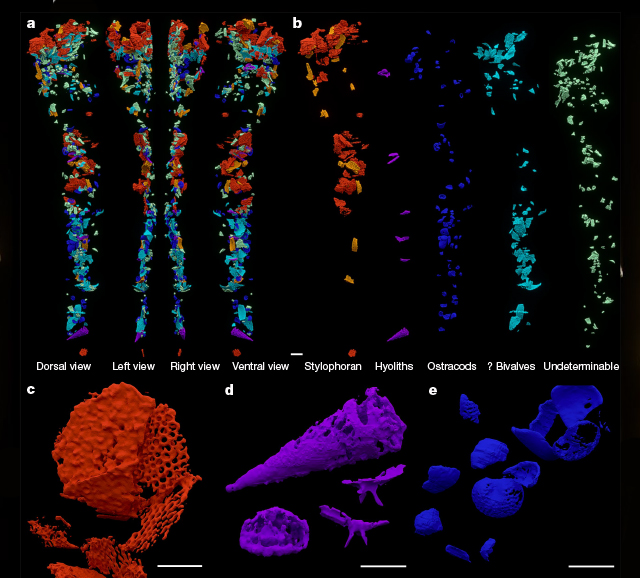

The complete Bohemolichas incola trilobite was preserved in fine 3D details within encasing siliceous pebbles called Rokycany Balls. Inside this specimen's staggering 465 million-year-old digestive system paleontologist Petr Kraft from Charles University in the Czech Republic and colleagues found tightly packed fragments of shell.

The shells did not show signs of being dissolved with their sharp edges still intact, suggesting the trilobite's digestive system isn't acidic but rather neutral or basic along its entire length, the researchers explain. This is how modern crustaceans and spiders do their digesting too – animals belonging to the two different modern groups in contention for the closest trilobite relatives.

Almost the entire digestive tract was packed full, with some fragments still large enough to be identified. Those bits and bobs of trilobite prey all belong to benthic invertebrates that dwelled at the bottom of the sea during the Ordovician.

The most common shell fragments were ostracods; small shrimp-like crustaceans with some descendants still alive today.

The trilobite had also devoured hyolith conch snails, extinct starfish and sea urchin relatives called stylophora and other thin-shelled animals that are likely bivalves.

"The non-selective feeding behavior of B. incola suggests that it was predominantly an opportunistic scavenger," the team write in their paper. "B. incola can be considered as a light crusher and chance feeder, hoovering up dead or living animals that were either easily disintegrated or small enough to be swallowed whole."

The trilobite's full digestive tract, along with some distortions in its thorax suggest the animal may have been about to molt.

Arthropods have to change their shell-like exoskeleton in order to grow, in a process called molting. Before molting, an arthropod's digestive tract often swells up to help push off the old 'shell' and make room for the new one.

"We suggest that the feeding behavior of the trilobite may have resembled the corresponding life cycles of modern crustaceans," Kraft and team conclude.

"Most of the time, the intestine was empty or moderately filled, with occasional and swift overfeeding actions linked to specialized physiological requirements."

Their research was published in Nature.