DNA analysis of a 110,000-year-old fossilised tooth found in a Siberian cave has provided further evidence for the existence of the Denisovans - a recently identified extinct species of human - and suggests that they likely co-existed and perhaps even interbred with Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens.

The analysis also revealed that the Denisovans were around at least 60,000 years earlier than we thought, were almost as genetically diverse as modern Europeans, and suggests that they might have been breeding with another mysterious relative of modern humans that scientists have yet to identify.

"The world at that time must have been far more complex than previously thought," study author Susanna Sawyer from the the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany told Michael Greshko at National Geographic. "Who knows what other hominids lived and what effects they had on us?"

Scientists only became aware of the existence of Denisovans five years ago, when DNA analysis of a single Denisovian tooth and finger bone discovered in a cave in the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia revealed that they belonged to the same lineage of ancient hominins.

The remains were dated to around 50,000 years old, and the team behind the discovery said the Neanderthals were their closest known relatives, having likely split off from each other on the human family tree about 400,000 years ago. It's thought that they split off from Homo sapiens 100,000 years before that.

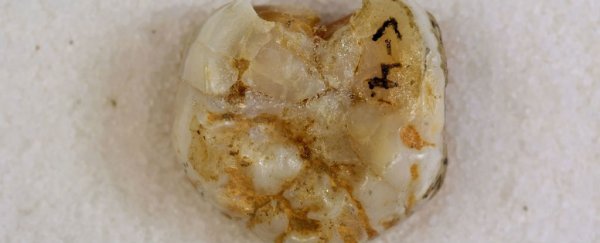

Now, thanks to the discovery of a second wisdom tooth, called Denisova 8, in the same Siberian cave back in 2010, scientists are painting a more detailed picture of the Denisovans. While DNA from the tooth can tell us little about how they behaved or what they looked like - although it seems they had big jaws, as Denisova 8 was so big, it was first mistaken for a bear's tooth - Sawyer and her team have been able to tease out a number of fascinating insights.

Firstly, it's thought that while the Neanderthals struggled with the harsh Siberian climate, the movement of the Denisovans suggests that they thrived in the bitter cold for many generations, spreading throughout Europe and Asia before mysteriously disappearing from the fossil record.

Carl Zimmer explains at The New York Times:

"[Study co-author Bence Viola from the University of Toronto] speculated that the Neanderthals became inbred because ice age glaciers drove them into isolated refuges in southern Europe. The Denisovans, though, were able to move south through large regions of Asia that were not covered by glaciers.

Another clue that Denisovans traveled far south of Siberia is in the DNA of living humans. Chunks of Denisovan DNA are found in Australian aborigines, New Guineans and Polynesians."

Because they were not so boxed-in as the Neanderthals, the Denisovans were surprisingly diverse, the researchers comparing them to modern Europeans in terms of genetic diversity. This could have been helped by the Denisovans interbreeding with not just Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, but DNA fragments that belong to neither of these species points to a fourth, unidentified hominin that could have existed at the time.

"If you would have told me five years ago I would be talking about species we don't have any fossils for, I would have thought you were crazy," molecular anthropologist Todd Disotell from New York University, who was not involved in the study, told The New York Times.

Now someone just has to find them. Pretty good motivation to drop everything and become an anthropologist, right?

The results have been published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.