The discovery of a Neanderthal child with what appeared to be significant health complications indicative of Down syndrome has swayed debate over the origins of communal healthcare within our species.

In a new study, a research team from Spain says the fact the child survived to at least age six – despite severe hearing loss and balance issues – demonstrates the complexity of social care among our closest evolutionary relatives, the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis).

The child's survival relied on more support than a mother could give, suggesting assistance from a wider group in challenge of ideas that prehistoric caregiving only extended to immediate family or those who could reciprocate the favor.

Neanderthals have long been known to care for the sick and injured in their communities, but there's debate around the motivations behind this behavior.

Fossils from children with conditions that would have needed the help of other group members to survive offer a rare opportunity to study this further.

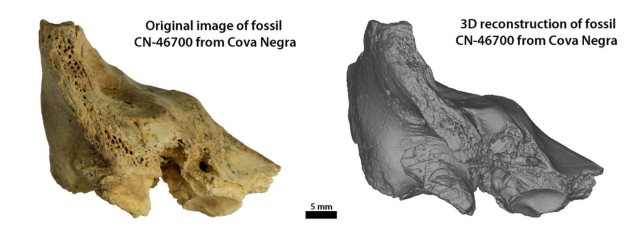

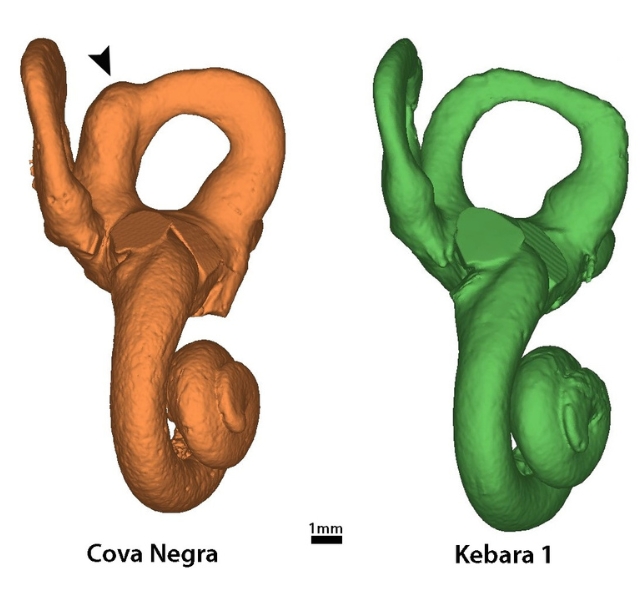

The fossil, coded CN-46700, is a temporal bone from a set of Neanderthal remains excavated in 1989 from the Cova Negra cave site in Spain, occupied by the species between 273,000 and 146,000 years ago. Researchers used micro CT scans to construct a 3D model of the original fossil for analysis.

The analysis revealed CN-46700 had characteristics typical of Neanderthals, and developmental features indicating the child was older than six years. They also found signs of health issues including a smaller cochlea and abnormalities in the shortest ear canal that would have caused hearing loss and severe dizziness.

"The only syndrome that is compatible with the entire set of malformations present in CN-46700 is Down syndrome," University of Alcala paleoanthropologist Mercedes Conde-Valverde and her colleagues write.

"Consequently, all available evidence suggests that the CN-46700 individual probably had Down syndrome, which is the most common human genetic disorder and it is also present in great apes."

Living to the age of six is remarkable – of three known examples of children born with Down syndrome in the Iron Age, none survived longer than 16 months. Other fossil records of inner ear abnormalities that affect hearing and balance belong to adults with features commonly resulting from infections, not conditions present at birth.

Down syndrome usually results from a random error in cell division during egg or sperm formation, leading to an extra copy (or partial copy) of chromosome 21 in the body's cells. This impacts development and increases risk of multiple health issues, including heart defects and epilepsy.

In 1900, people with Down syndrome had a 9-year life expectancy; today, advances in medicine and social support mean those in developed countries can live over 60 years.

Down syndrome often involves impairments that affect growth, physical and cognitive development, and motor skills. Children frequently have delays in walking and talking, problems with balance and coordination that increase the risk of falls, and difficulty breastfeeding due to weak muscle tone.

The symptoms experienced by CN-46700 "would have included, at a minimum, severe hearing loss and markedly reduced sense of balance and equilibrium," write Conde-Valverde and team.

Neanderthals had a demanding lifestyle and it's unlikely that a mother could have provided all the necessary care to a child with Down syndrome, while also performing daily tasks.

The survival of CN-46700 shows that our hominin cousin received extensive and ongoing support from the broader group, even though the child was unable to provide direct, equivalent reciprocation. This suggests the caregivers may have been driven by compassion.

"The presence of this complex social adaptation in both Neanderthals and our own species suggests a very ancient origin within the genus Homo," the authors conclude.

The research has been published in Science Advances.