An international team of scientists has announced the discovery of an extraordinary fossilized nest in China, preserving at least eight separate dinosaurs from 70 million years ago.

The clutch of ancient eggs belongs to a medium-sized adult oviraptor, and we know that because the parent is actually part of the fossil. The skeleton of this ostrich-like theropod is positioned in a crouch over two dozen eggs, at least seven of which were on the brink of hatching and still contain embryos inside.

The ancient scene is unprecedented, and provides the first hard evidence that dinosaurs were brooding parents, laying their eggs and incubating them for quite a long time.

"This kind of discovery - in essence, fossilized behavior - is the rarest of the rare in dinosaurs," says paleontologist Matt Lamanna from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH).

"Though a few adult oviraptorids have been found on nests of their eggs before, no embryos have ever been found inside those eggs."

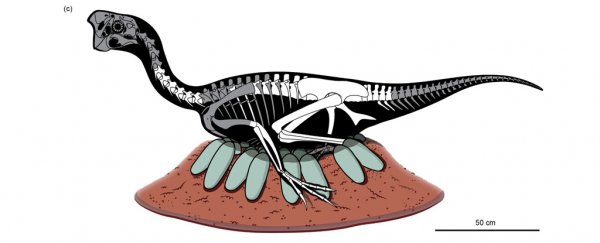

The 70-million-year-old fossil. (Shundong Bi/Indiana University of Pennsylvania)

The 70-million-year-old fossil. (Shundong Bi/Indiana University of Pennsylvania)

Since the 1980s, paleontologists have unearthed numerous dinosaur nests containing fossilized eggs. Some rare ones have even been found with the parent's skeleton sitting on top. Other oviraptor eggs suggest they might have been a blue-green color.

Inferring behavior from these fossils, however, has proved problematic. While it seems the oviraptor parents are brooding on their nests, it's also possible these dinosaurs perished while laying or guarding their eggs, not necessarily incubating them. This is more similar to how crocodiles deal with their nests, not modern birds.

The new specimen was recovered from the Nanxiong Formation of Ganzhou in South China - a region renowned for the world's largest collection of fossilized dinosaur eggs - but it's unlike anything scientists have found before.

The relationship between dinosaur parent and embryo has never been closer than this. The body of the adult oviraptor is preserved in "extremely close proximity to the eggs", with little to no sediment in between.

In at least seven of the eggs, embryonic material was found exposed, including ossified bones in identifiable shapes.

One of the eggs may actually contain a complete skeleton, with its vertebrae, dorsal ribs, a humerus, both ilia and femora, and a tibia laid out in a curled position.

Analyzing the oxygen isotopes of these embryos, researchers found the estimated incubation temperature was consistent with the body temperature of the parent, sitting somewhere between 30 to 38 degrees Celsius (86 to 100 degrees Fahrenheit).

"In the new specimen, the babies were almost ready to hatch, which tells us beyond a doubt that this oviraptorid had tended its nest for quite a long time," explains Lamanna.

"This dinosaur was a caring parent that ultimately gave its life while nurturing its young."

Artwork of oviraptor dinosaur brooding on a nest of blue-green eggs. (Zhao Chuang/PNSO)

Artwork of oviraptor dinosaur brooding on a nest of blue-green eggs. (Zhao Chuang/PNSO)

Interestingly enough, however, not all the embryos were at the same stages of development. This suggests the clutch may ultimately have hatched at different times - a feature that was thought to show up much later, in only some types of birds.

While oviraptors are often considered an intermediate stage in this evolutionary process, it looks as though they might have independently moved away from simultaneous hatching, and this suggests the evolution of bird reproduction was not a simple linear process.

Most modern birds will wait until all their eggs are laid before incubating them - sometimes with the help of both mother and father - and this leads to synchronous hatching.

While oviraptors may also have waited to incubate until all the eggs had been laid, the authors suggest the upper eggs might have been closer to the brooding adult and therefore could have developed more quickly. This, however, is just an idea. We'll need more data to figure out why some eggs would have hatched earlier than others.

In other ways, however, the oviraptor shares similar traits to modern birds. The sex of the fossilized parent, for instance, may have been male, which suggests the father might have also taken part in brooding, similar to ostrich mothers and fathers, who take turns incubating their young.

The sex of the adult oviraptor is still under debate (it could be a male or a female based on available data), but the idea matches other analyses of theropod nests, which suggest some level of paternal care.

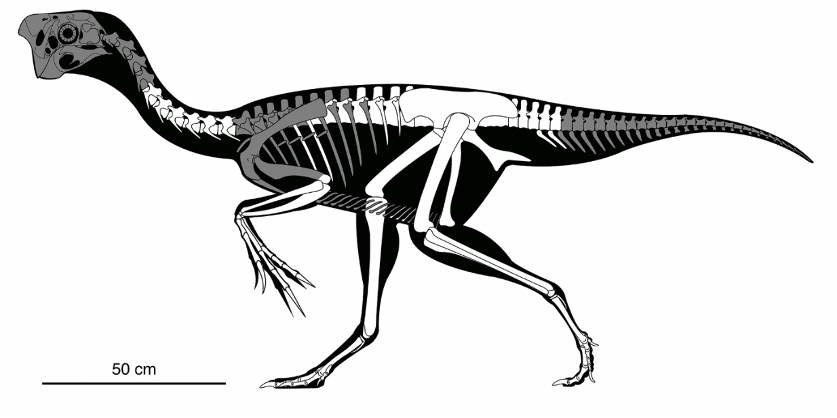

Artwork of the adult oviraptor skeleton; preserved bones shown in white. (Andrew McAfee/Carnegie Museum of Natural History)

As if all that reproductive information wasn't enough, this remarkable fossil has also given us a glimpse at the oviraptor's potential diet. For the first time, scientists have found small stones in the stomach of this type of dinosaur, which would have probably been swallowed to aid digestion.

"It's extraordinary to think how much biological information is captured in just this single fossil," says paleontologist Xing Xu from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing.

"We're going to be learning from this specimen for many years to come."

The study was published in the Science Bulletin.