More than 47 million years ago, giant carnivorous ants swarmed the prehistoric forest floors of North America looking for prey.

'Giant' is no exaggeration either. Some ancient colonies that lived in what is now the state of Wyoming were ruled by queens the size of hummingbirds.

Those aren't even the biggest ants to ever stride across Earth's surface. The largest known ant queen to have ever lived was a relative found in fossil form over in Germany. She had the body mass of a wren, was more than 5 centimeters (2 inches) long, and had wings that extended 16 centimeters. Her army of workers is thought to have hunted anything in their wake, including perhaps lizards, mammals, and birds.

Like modern ants, these ancient insects were more than likely ectothermic, meaning they struggle to survive without an appreciable amount of heat in their environment. Just how far the temperature can drop before they fail to thrive largely depends on their body size.

While animals that can modify their own temperatures withstand colder climates by maximizing their mass and minimizing their skin, animals that need to absorb heat from their environment do better with more surface area and less volume. Today, bigger ant queens are found closer to the tropics, for example.

So how did ancient giant ants cross the cold Bering land bridge that once connected Russia to Alaska to get from Europe to Wyoming?

In 2011, researchers suggested that this temperate land bridge once included a climate-controlled 'gate'. During brief periods of global warming, that gate may have swung open to allow cold-blooded organisms, like ants, to comfortably pass from one continent to another.

A newly discovered fossil of an ancient ant queen now complicates that hypothesis.

It, too, belongs to the same genus as the giant ants found in Wyoming and in Germany, called Titanomyrma.

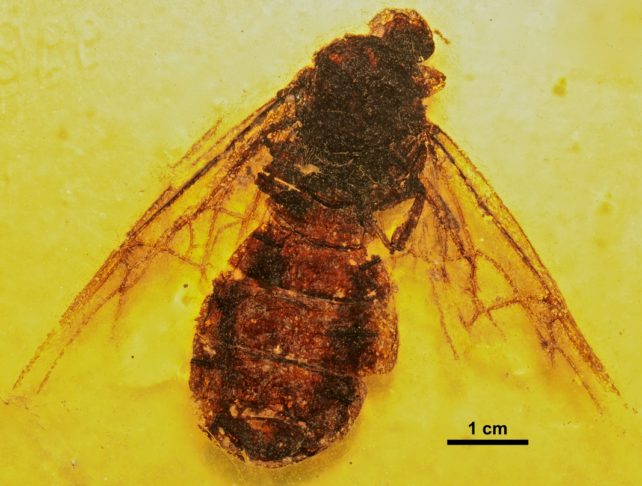

But this one was found in British Columbia in Canada – the first fossil of its kind to appear in such a cold climate.

Scientists can't be sure of its size due to its squashed nature, but there's a chance it was as big as its Wyoming counterpart.

"If it was a smaller species, was it adapted to this region of cooler climate by reduction in size and gigantic species were excluded as we predicted back in 2011?" wonders paleontologist Bruce Archibald from Simon Fraser University (SFU).

"Or were they huge, and our idea of the climatic tolerance of gigantic ants, and so how they crossed the Arctic, was wrong?"

The Canadian Titanomyrma is not in great condition, which means it can't be assigned to a specific species, but it is close in age to other fossils of its kind found in Europe and Wyoming.

Depending on which way it was compressed, the organism could have originally been either 3 or 5 centimeters in length.

The shorter estimate would make it 65 percent smaller than its Wyoming counterpart, supporting the idea that gigantic ants require hot climates and could only have been let through the Bering land bridge's climate gate during a period of global warming.

The larger measurement suggests that these ancient ants had more cold tolerance than we thought and could have crossed the land bridge at any time.

The only way to differentiate between those scenarios is to find more fossils.

"Do our ideas of Titanomyrma's ecology, and so of this ancient dispersal of life, need revision?" asks Archibald.

"For now, it remains a mystery."

The study was published in The Canadian Entomologist.