A new global analysis of the distribution of forests and woodlands has 'found' 467 million hectares of previously unreported forest – an area equivalent to 60 percent of the size of Australia. ![]()

The discovery increases the known amount of global forest cover by around 9 percent, and will significantly boost estimates of how much carbon is stored in plants worldwide.

The new forests were found by surveying 'drylands' – so called because they receive much less water in precipitation than they lose through evaporation and plant transpiration. As we and our colleagues report today in the journal Science, these drylands contain 45 percent more forest than has been found in previous surveys.

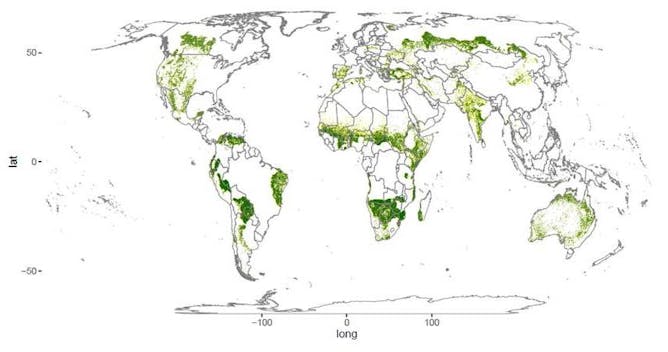

We found new dryland forest on all inhabited continents, but mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, around the Mediterranean, central India, coastal Australia, western South America, northeastern Brazil, northern Colombia and Venezuela, and northern parts of the boreal forests in Canada and Russia.

In Africa, our study has doubled the amount of known dryland forest.

Bastin et al., Science (2017)

Bastin et al., Science (2017)

With current satellite imagery and mapping techniques, it might seem amazing that these forests have stayed hidden in plain sight for so long. But this type of forest was previously difficult to measure globally, because of the relatively low density of trees.

What's more, previous surveys were based on older, low-resolution satellite images that did not include ground validation.

In contrast, our study used higher-resolution satellite imagery available through Google Earth Engine – including images of more than 210,000 dryland sites – and used a simple visual interpretation of tree number and density.

A sample of these sites were compared with field information to assess accuracy.

Unique opportunity

Given that drylands – which make up about 40 percent of Earth's land surface – have more capacity to support trees and forest than we previously realised, we have a unique chance to combat climate change by conserving these previously unappreciated forests.

Drylands contain some of the most threatened, yet disregarded, ecosystems, many of which face pressure from climate change and human activity.

Climate change will cause many of these regions to become hotter and even drier, while human expansion could degrade these landscapes yet further.

Climate models suggest that dryland biomes could expand by 11 to 23 percent by the end of the this century, meaning they could cover more than half of Earth's land surface.

Considering the potential of dryland forests to stave off desertification and to fight climate change by storing carbon, it will be crucial to keep monitoring the health of these forests, now that we know they are there.

Climate policy boost

The discovery will dramatically improve the accuracy of models used to calculate how much carbon is stored in Earth's landscapes.

This in turn will help calculate the carbon budgets by which countries can measure their progress towards the targets set out in the Kyoto Protocol and its successor, the Paris Agreement.

Our study increases the estimates of total global forest carbon stocks by anywhere between 15 gigatonnes and 158 gigatonnes of carbon – an increase of between 2 percent and 20 percent.

This study provides more accurate baseline information on the current status of carbon sinks, on which future carbon and climate modelling can be based. This will reduce errors for modelling of dryland regions worldwide.

Our discovery also highlights the importance of conservation and forest growth in these areas.

The authors acknowledge the input of Jean-François Bastin and Mark Grant in the writing of this article.

The research was carried out by researchers from 14 organisations around the world, as part of the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation's Global Forest Survey.

Andrew Lowe, Professor of Plant Conservation Biology, University of Adelaide and Ben Sparrow, Associate professor and Director - TERN AusPlots and Eco-informatics, University of Adelaide.

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Read the original article.