It turns out that our galaxy looks the way it does today thanks to a run-in with something called the 'Gaia Sausage'.

As greasy as space is, we're not talking cosmic processed foods here. Rather, astronomers have found signs that a small galaxy smashed into the Milky Way billions of years ago, leaving behind a mess of stars with some rather unusual orbits.

So, what makes this cosmic object a 'sausage'? Cambridge University astronomer Wyn Evans says it all came down to the paths of the stars following the impact.

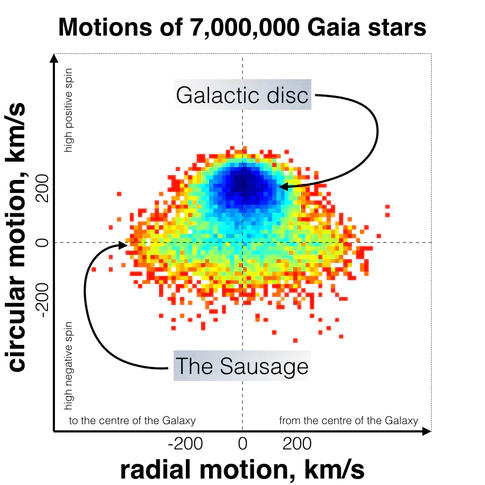

"We plotted the velocities of the stars, and the sausage shape just jumped out at us," says Evans.

"These Sausage stars are what's left of the last major merger of the Milky Way."

If you squint and use your imagination, you can definitely see something sausage-shaped in the graph below.

(V. Belokurov (Cambridge, UK) and Gaia/ESA)

(V. Belokurov (Cambridge, UK) and Gaia/ESA)

Collisions between galaxies aren't all that unusual, and the Milky Way has had its fair share of dust-ups with surrounding crowds of stars.

One small merger thought to have occurred just 100 million years ago left the galaxy "ringing like a bell" with huge ripples observed in our corner of the galaxy.

But this one wasn't just any puff of stars and dust. Additional analysis noticed it was accompanied by at least eight star clusters, meaning as far as small galaxies go it had to have been on the slightly chunky side of around 10 billion solar masses.

"While there have been many dwarf satellites falling onto the Milky Way over its life, this was the largest of them all," says Sergey Koposov of Carnegie Mellon University.

Astronomers studied a sample of around 200,000 main sequence stars in our neighbourhood taken using data from the European Space Agency's Gaia spacecraft and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

Using mathematical models to rewind and unravel their paths, the researchers arrived at a monumental event in the history of our galaxy roughly 8 to 10 billion years ago.

The impact would have been so cataclysmic, the Milky Way could have been fractured. In the very least, its recovery from the shake-up would have given it a new shape before settling again into its familiar bulging disc.

Galaxies come in a variety of shapes and sizes, but certain characteristics of this spiralling disc we call home have been hard to explain.

For one thing, we sit inside a diffuse halo of stars, many of which are older than the stars scattered throughout the flat plane. There have been attempts to explain this fact over the decades, but astronomers have continued to debate the details.

This new model puts a new spin on previous observations by suggesting a younger Milky Way was hit with an incoming ball of stars and dust, contributing to a dense nucleus that came to be surrounded by a halo.

The Sausage Galaxy might have long turned into mince-meat, but its remnants still carry plenty of clues of its origins.

"The Sausage stars are all turning around at about the same distance from the centre of the galaxy," says senior author Alis Deason of Durham University.

The stars long, radial velocities aren't unlike the comets in our own Solar System, dipping in and out of the galactic centre in tight U-turns and changing the density of the bulge. As the disc continued to stretch over time, those orbits elongated.

Given the size of the Milky Way, snapping a galactic selfie isn't exactly easy, meaning we've only got a vague idea of what our home looks like. Models like this could help us build a clearer picture, and further analysis of Gaia data will be used to test some of the predictions made by the team.

But as big as Gaia Sausage was, the Milky Way is on a far more impressive collision course with a neighbour that's at least as big as us.

In around 4 billion years, Andromeda and the Milky Way will swirl together and mix stars in a slow dance that will once again change the shape of our galaxy in a monumental way.

We won't be around to see it, but learning more about our past could help us accurately predict what the new mammoth sized Milkomeda galaxy might look like.

This research was published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.