Dark matter is confusing at the best of times. But now astronomers have made an extraordinary and perplexing discovery - the first ever observation of a galaxy with almost no dark matter at all.

We still don't know what exactly dark matter is, but it's currently the most elegant explanation for some of the dynamics observed in galaxies. Most galaxies are even thought to have more dark matter than regular matter.

So this dark matter free galaxy is doubly perplexing.

And according to current thinking about galactic evolution, dark matter is not just a component, but even a requirement for galaxies to be born in the first place.

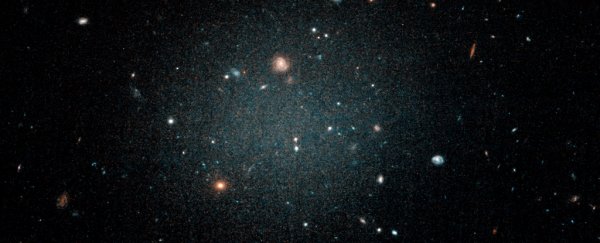

The galaxy, called NGC1052-DF2, is about 65 million light-years away in the constellation of Cetus.

It's about the same physical size as the Milky Way, but only has one star for every 200 found in the Milky Way.

It's so sparse that you can see right through it to the galaxies behind it in its Hubble photograph.

Because of this lack of stars, and because of the lack of dark matter, NGC1052-DF2 is very low mass.

Its mass simply matches up with the amount of observed baryonic, or normal, matter inside it.

All other galaxies ever observed have mass that can't be accounted for just by the ordinary matter inside them.

"Finding a galaxy without dark matter is unexpected because this invisible, mysterious substance is the most dominant aspect of any galaxy," said lead author Pieter van Dokkum of Yale University.

"For decades, we thought that galaxies start their lives as blobs of dark matter. After that everything else happens: gas falls into the dark matter halos, the gas turns into stars, they slowly build up, then you end up with galaxies like the Milky Way. NGC1052-DF2 challenges the standard ideas of how we think galaxies form."

In addition, the galaxy has huge implications in the study of dark matter. Because - simply by having none, but having stars - NCG1052-DF2 helps to prove that dark matter really exists in other galaxies and is separate from baryonic matter.

Van Dokkum and his team first spotted the galaxy using the Dragonfly Telescope Array, which had been purpose-built by the team for imaging very faint objects.

They followed up with a number of different telescopes to peer inside the galaxy, classified as an ultra-diffuse galaxy because of its large size and faintness.

They found an unusually large population of globular clusters, globe-shaped clusters of typically between 100,000 and 1 million stars. They also found these were moving much more slowly in orbit around the galaxy's core than expected.

The higher a galaxy's mass, the faster objects within it move, so they were able to use this information to calculate the mass of NGC1052-DF2.

The lack of dark matter makes it completely unlike any other galaxy observed to date.

"It's like you take a galaxy and you only have the stellar halo and globular clusters, and it somehow forgot to make everything else," van Dokkum said.

"There is no theory that predicted these types of galaxies. The galaxy is a complete mystery, as everything about it is strange. How you actually go about forming one of these things is completely unknown."

There is one possible explanation. NGC1052-DF2 is in a galaxy cluster dominated by an enormous elliptical galaxy called NGC 1052. This could have played a role in the galaxy's formation.

According to the paper, the smaller galaxy could have formed from gas that was collapsing towards a forming NGC 1052 but that fragmented off before it got there.

It's also possible that it was created from gas that was ejected when two other galaxies were merging. Or that some tremendous, cataclysmic event swept all the gas and dark matter from NGC1052-DF2.

None of these speculative hypotheses are able to explain all the galaxy's peculiarities, though. So the team is using Dragonfly to search for more galaxies like NGC1052-DF2, in the hope of being able to start putting together a statistical picture.

"Every galaxy we knew about before has dark matter, and they all fall in familiar categories like spiral or elliptical galaxies," van Dokkum said.

"But what would you get if there were no dark matter at all? Maybe this is what you would get."

The team's paper has been published in the journal Nature.