A fresh look at a triceratops skeleton suggests the dinosaur was once stabbed in the head by another of its kind.

The unique three-horned head of the triceratops is a big part of this species' fame, and yet researchers are still trying to figure out how it once used its unusual, frilly skull.

The large boney frills at the back of the triceratops head are often riddled with punctures and fractures, which have led some experts to suggest the herbivore was prickly with its own kind and maybe even its predators, like the Tyrannosaurus rex.

To protect itself, a triceratops might have used its horns as weapons and its frill as a shield. But there are other explanations, too.

Some experts think neck frill lesions are signs of natural ageing, while still others suspect the frills are ornamental, used to impress the other sex or competitors of the same sex.

Now, one of the largest triceratops skeletons ever found has weighed in on the debate, and it's made quite the impression.

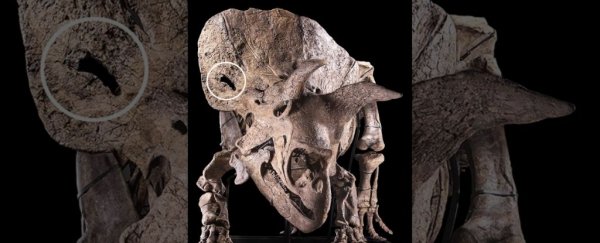

The skeleton has been nicknamed Big John; when it was discovered in 2014, researchers noticed its neck frill was completely punctured through.

The puncture wound found on Big John's neck frill. (Ferrara A., and Briano I.)

The puncture wound found on Big John's neck frill. (Ferrara A., and Briano I.)

Putting the frill under the microscope, experts have now found evidence that the triceratops was attacked by its own species while its back was turned.

In the past, paleontologists have used the wounds on neck frills to come up with ways in which the triceratops might have fought with each other. For instance, the dinosaurs might have locked their upper horns, or used their nose horn as a weapon.

But neither of these fighting techniques explains the wound on Big John.

"It appears likely that the wound was instead inflicted from behind Big John, whereby the rival's horn would have penetrated the frill and then slipped towards the rostrum, giving this lesion the shape of a keyhole," the authors write.

Perhaps, instead of a neck frill defending the dinosaur's body from a head-on attack, these large bony shields protected the triceratops head from behind.

In the case of Big John, the neck frill appears to have served its purpose. The dinosaur ultimately made it out of the scuffle alive, but its injury was so severe that even when the triceratops finally died, probably about half a year later, it was still in the process of healing.

Or, at least, it showed signs of bone healing that closely match mammals. Experts still don't really know how dinosaur skeletons recovered from wounds, but if the authors behind this study are right, it could be remarkably similar to the way our own bones heal.

Microanalysis of Big John's wound found the surrounding bone tissue to be porous with lots of blood vessels. In mammals and birds, this is a sign that new bone is forming. The presence of little pits in the bone also suggests some bone remodeling was happening to heal parts of the frill.

What ultimately killed Big John is unknown, but the preservation of his frill suggests he was quite the survivor.

"This study confirms the existence of intraspecific fighting in Triceratops," the authors conclude.

"Further histological and microanalytical investigations on fossil remains with traumatic lesions might shed light on the bone physiopathology of these reptiles."

The study was published in Scientific Reports.