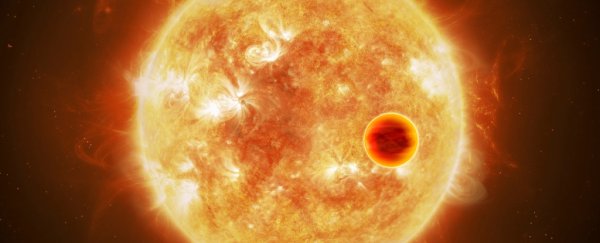

A newly discovered exoplanet is one of the most extreme discovered yet.

Its name is TOI-2109b, an absolute beast of a gas giant clocking it at 1.35 times the size and 5 times the mass of Jupiter. Oh, and it has a death wish: It's on such a close orbit with its host star that it whirls around once every 16 hours.

That's the closest orbit we've ever discovered for a gas giant, so close that it is spiraling ever closer to the star on a trajectory of doom, with half of it scorched by its host star's burning heat. On its day side, TOI-2109b is thought to reach temperatures of 3,500 Kelvin (3,227 degrees Celsius, or 5,840 degrees Fahrenheit). That's hotter than some stars.

It's the second-hottest exoplanet ever discovered, putting it in the category of ultrahot Jupiters. Astronomers hope it can tell us more about how these extreme exoplanets come to exist, as well as the interactions between a star and a perilously closely orbiting exoplanet.

"In one or two years, if we are lucky, we may be able to detect how the planet moves closer to its star," said astronomer Ian Wong of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. "In our lifetime, we will not see the planet fall into its star. But give it another 10 million years, and this planet might not be there."

Hot and ultrahot Jupiters are fascinating subcategories of exoplanets.

As the name suggests, they are massive gas giants like Jupiter. Unlike Jupiter, however, they orbit their host star incredibly closely, on orbits of fewer than 10 days (for comparison, Jupiter's orbital period is a rather more sedate 12 years). At such close distances, these exoplanets are very hot indeed, often evaporating under the intense heat.

According to current models of planet formation, hot Jupiters are quite a conundrum. A gas giant can't form that close to its star since the gravity, radiation, and intense stellar winds ought to keep the gas from clumping together.

Yet we've discovered hundreds. Currently, astronomers believe that these exoplanets form farther away from their host stars and migrate inwards.

"From the beginning of exoplanetary science, hot Jupiters have been seen as oddballs," said astrophysicist Avi Shporer of MIT's Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. "How does a planet as massive and large as Jupiter reach an orbit that is only a few days long? We don't have anything like this in our Solar System, and we see this as an opportunity to study them and help explain their existence."

To piece together the evolutionary puzzle of the hot Jupiter, astronomers look for as many as possible, hoping to catch them at different stages of their lifespans. TOI-2109b is the closest to death by orbital decay that we've found yet.

A diagram of the changes in a star's light as an exoplanet orbits. (J. Winn, arXiv, 2014)

A diagram of the changes in a star's light as an exoplanet orbits. (J. Winn, arXiv, 2014)

It was detected by NASA's exoplanet-hunting space telescope TESS, which looks for small, evenly spaced dips in the light of a star. This is one of the telltale signals that something is orbiting that star.

The amount by which the light of the star dips can tell us the size of the orbiting body. Small shifts in the star's light as it moves around on the spot, tugged by the gravitational pull of the exoplanet, can tell us its mass.

TOI 2109b is orbiting a yellow-white star 1.7 times the size and 1.4 times the mass of the Sun, around 855 light-years away. TOI 2109b and its sun are so close that the distance between them is around just 2.4 million kilometers (1.5 million miles). That's just 1.6 percent of the distance between the Sun and Earth.

At such close proximity, the exoplanet is likely tidally locked to its host star, with one side permanently facing the star. That side, studied as the exoplanet rotated in and out of view, reaches the insane temperature of 3,500 Kelvin, but the night side – facing away from the star – is a little harder to understand.

"The planet's night side brightness is below the sensitivity of the TESS data, which raises questions about what is really happening there," Shporer said.

"Is the temperature there very cold, or does the planet somehow take heat on the day side and transfer it to the night side? We're at the beginning of trying to answer this question for these ultrahot Jupiters."

What the research team could measure was the rate at which TOI 2109b is spiraling in towards its star. It grows closer by 10 to 750 milliseconds per year. That's the fastest inspiral rate of any hot Jupiter we've discovered to date.

The team hopes that future studies of TOI-2109b, perhaps with the soon-to-be-launched James Webb Space Telescope (knock wood), will reveal some of the stresses hot Jupiters undergo as they undertake their spirals of death.

"Ultrahot Jupiters such as TOI-2109b constitute the most extreme subclass of exoplanet," Wong said.

"We have only just started to understand some of the unique physical and chemical processes that occur in their atmospheres – processes that have no analogs in our own solar system."

The research has been published in The Astronomical Journal.