One advantage to planetary science is that insights from one planet could explain phenomena on another. We understand Venus' greenhouse gas effect from our own experience on the Earth, and Jupiter and Saturn share some characteristics.

But Jupiter also provides insight into other, farther out systems, such as Uranus and Neptune.

Now, a discovery from a spacecraft orbiting Jupiter might have solved a long-standing mystery about Uranus and Neptune – where has all the ammonia gone?

Scientists have long noticed an absence of ammonia in the atmospheres of Uranus and Neptune when compared to the amounts seen on Jupiter and Saturn.

Many considered that fact strange as planetary formation models suggested that all gas giants originated from the same "primordial soup," so their compositions should be similar.

Theories abounded as to where the ammonia had gone, but a closer inspection of Jupiter itself hints at a potential explanation.

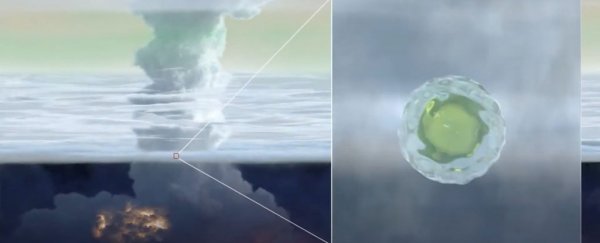

Juno, a probe that is currently exploring the Jupiter system, noticed that ammonia in the upper atmosphere formed "mushballs" by merging with water also present in the atmosphere.

Like hailstones, these mushballs are more liquid than traditional hailstones, as the ammonia liquefies water comes into contact with even at extremely low temperatures, such as those found in Jupiter's upper atmosphere.

These amalgamated mushballs can grow to be bigger than some of the more giant hailstones on Earth. They are also prone to rapidly falling through the atmosphere, dragging their constituent parts down out of the upper reaches of the atmosphere.

As they get closer to the center of Jupiter, the temperature rises, vaporizing the ammonia and water and allowing them to climb back towards the observable upper reaches.

(NASA /JPL-Caltech/SwRI /CNRS)

(NASA /JPL-Caltech/SwRI /CNRS)

According to Tristan Guillot of the CRNS Laboratoire Lagrange, the same process might be happening on Neptune and Uranus, but the mushballs hold the ammonia down in the lower atmosphere for longer, without as much chance of releasing it back up to observable altitudes.

At such low altitudes, the ammonia would appear to be missing with current observational capabilities. The upper layers of clouds would obscure any ammonia reading, making it appear as if it vanished.

To see the vanished ammonia would require a dedicated mission specifically to explore the lower atmospheres of the outer planets. Some missions have been touted in the past, but none are currently operational.

As Dr. Guillot points out, understanding the outer planets in our own solar system would help us understand the atmospheres of exoplanets far beyond our own solar system. Perhaps it is time to send a dedicated probe out to learn more about our farthest out planetary neighbors.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.