A menacing heatwave is brewing in the Pacific Ocean, and it's got scientists worrying about the return of 'the Blob'.

Roughly five years ago, a huge patch of unusually warm ocean water appeared off the coast of North America, stretching from Mexico's Baja California Peninsula all the way up to Alaska.

It was nicknamed the Blob, after a horror film monster that consumes everything in sight. The heatwave, which lasted for several years, was an equally indiscriminate killer.

According to estimates, during this time the southern coast of Alaska lost more than 100 million Pacific cod. Thousands of seabirds were found washed up on the shore, and about half a million were decimated in total. In one year alone, populations of humpback whales dropped by 30 percent. Salmon, sea lions, krill, and other marine animals also vanished in astonishing numbers, as toxic algae bloomed.

The Blob caused ecosystems and industries alike immense losses - so much so that researchers from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are now closely tracking these events.

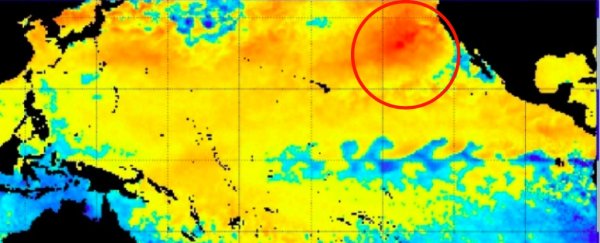

The current heatwave, they say, has not only popped up in the same area, it's grown in much the same way and is almost the same size.

Side by side, a comparison of both their early stages is ominous. Like the blob, the current marine heat wave emerged only a few months ago, as the winds that cool the ocean's surface began to die down.

"Given the magnitude of what we saw last time, we want to know if this evolves on a similar path," says marine ecologist Chris Harvey from the Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

(NOAA)

(NOAA)

Researchers tracking the phenomenon say the patch of ocean water is now roughly five degrees Fahrenheit above normal - just a degree or two less than temperatures during the last Blob.

Deep upwells of cold water have kept the heat wave from reaching the shore, but officials predict the event will likely have an impact on coastal ecosystems sometime this Northern Hemisphere fall.

"It's on a trajectory to be as strong as the prior event," says Andrew Leising, who developed a system for tracking and measuring marine heatwaves for NOAA.

"Already, on its own, it is one of the most significant events that we've seen."

In fact, according to records, which go back to 1981, it's the second largest marine heatwave ever recorded. And it comes just years after the last one.

Still, not all heatwaves are the same and these blobs are hard to predict. As quickly as they can emerge, they can also dissipate. Scientists say there's still a chance that weather patterns will change and that the current patch of warm water will cool down, but they're keeping their eye on it.

Research suggests that blobs and similar events are becoming more common worldwide. Earth's oceans are being heated at an unprecedented rate due to climate change, but currently it's hard to say if or how this shorter event is tied to deeper alterations.

"It's not clear to me that there's a simple link between persistence of this weather pattern and longer-term climate change," fisheries ecologist Nate Mantua told The Guardian.

"There might be. It's still an evolving field and there are a lot of open questions."

For now, researchers at NOAA are focused on tracking, predicting and mitigating the effects of marine heatwaves. During the last Blob, for instance, many whales died by getting trapped in fishing nets, as the animals moved closer to shore to avoid the warmer waters.

If fisheries and ecologists can work together, researchers hope we might be able to reduce some of the losses in the future. In the end, though, our control of the situation is pretty limited.

"There are definitely concerning implications for the ecosystem," says NOAA meteorologist Nick Bond, who is credited with naming the Blob.

"It's all a matter of how long it lasts and how deep it goes."