A tremendous, record-breaking quake that rocked Mars in May of this year was at least five times larger than the previous record-holder, new research has revealed.

It's unclear what the source of the quake was, but it was definitely peculiar. In addition to being the most powerful quake recorded yet on Mars, it was also the longest by a significant amount, shaking the red planet for 10 hours.

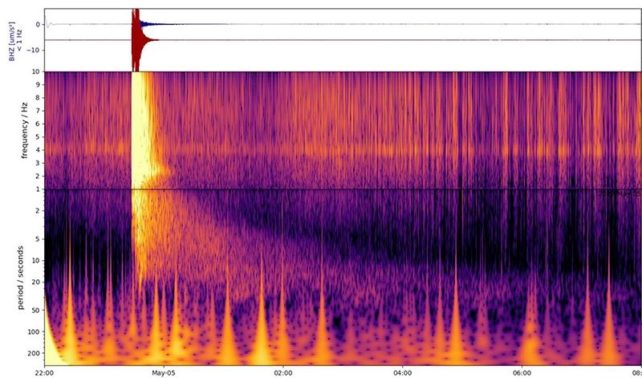

"The energy released by this single marsquake is equivalent to the cumulative energy from all other marsquakes we've seen so far," says seismologist John Clinton of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Switzerland, "and although the event was over 2000 kilometers (1200 miles) distant, the waves recorded at InSight were so large they almost saturated our seismometer."

The new analysis of the quake, published in Geophysical Research Letters, set its magnitude at 4.7. The previous record-holder was a magnitude 4.2 quake detected in August 2021.

That might not sound like a big quake by Earth standards, where the most powerful quake ever recorded tipped a magnitude of around 9.5. But for a planet that had been thought seismically inactive until NASA's InSight probe started recording its interior in early 2019, it's impressive.

Although Mars and Earth have a lot in common, there are some really key differences. Mars doesn't have tectonic plates; and nor does it have a coherent, global magnetic field, often interpreted as a sign that not much is happening in the Martian interior, since Earth's magnetic field is theorized to be the result of internal thermal convection.

InSight has revealed that Mars isn't as seismically quiet as we'd previously assumed. It creaks and rumbles, hinting at volcanic activity under the Cerberus Fossae region where the InSight lander squats, monitoring the planet's hidden innards.

But determining the activity status of the Martian interior isn't the only reason to monitor marsquakes. The way seismic waves propagate through and across the surface of a planet can help reveal density variations in its interior. In other words, they can be used to reconstruct the structure of the planet.

This is usually done here on Earth, but hundreds of quakes recorded by InSight have allowed scientists to build a map of the Martian interior, too.

The May quake may have been just one seismic event, but it seems it was an important one.

"For the first time we were able to identify surface waves, moving along the crust and upper mantle, that have traveled around the planet multiple times," Clinton says.

In two other, separate papers in Geophysical Research Letters, teams of scientists have analyzed these waves to try to understand the structure of the crust on Mars, identifying regions of sedimentary rock and possible volcanic activity inside the crust.

But there's more to be done on the quake itself. Firstly, it originated near, but not from, the Cerberus Fossae region, and could not be traced to any obvious surface features. This suggests that it could be related to something hidden below the crust.

Secondly, marsquakes usually have either a high or a low frequency, the former characterized by quick, short tremors, and the latter by longer, deeper waves with bigger amplitudes. This quake combined both frequency ranges, and the researchers aren't entirely sure why. However, it's possible that previously recorded high- and low-frequency marsquakes analyzed separately may be two parts of the same seismic event.

This could mean that scientists need to rethink how marsquakes are understood and analyzed, revealing even more secrets hiding under the deceptively quiet Martian surface.

"This was definitely the biggest marsquake that we have seen," says planetary scientist Taichi Kawamura of the Paris Globe Institute of Physics in France.

"Stay tuned for more exciting stuff following this."

The research has been published in Geophysical Research Letters.