When you're just a wee squishy frog trying to make your way in the wild jungles of Central and South America, you need to have some survival tricks up your clammy little sleeve.

Some frogs go on the offensive, striking out with powerful toxins. Others rely on quieter tactics – camouflage that helps them stay hidden from the eyes of voracious predators. For the Fleischmann's glass frog (Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni), living in the leafy treetops, that camouflage takes the form of transparency.

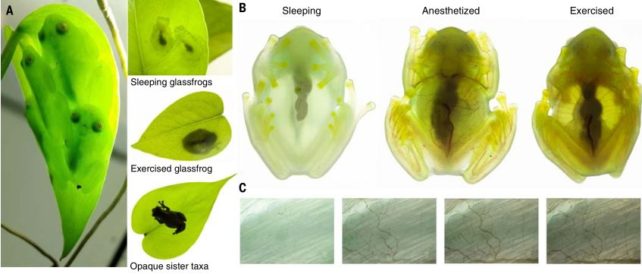

Typically nocturnal, the frogs limit the chances they'll become lunch by creeping about at night under the cover of darkness. During the day it finds a nice leaf to curl up on, where the green pigmentation of its skin helps it blend into the background.

But a sleeping glass frog still faces plenty of risks in the daytime, risks that aren't always easily mitigated by hiding beneath the foliage.

When sunlight streams down from above and penetrates a translucent leaf, a blobby little frog could form a clear frog-shaped silhouette that would stand out to hungry predators searching for a snack.

By having skin and flesh that lets significant amounts of sunlight pass through, Fleischmann's glass frog can cast a less-obvious shadow as it sleeps.

A team of scientists led by biologist Carlos Taboada of Duke University noticed that these little amphibians have a really fascinating trick that boosts this act of self-preservation. When a Fleischmann's glass frog has a snooze, its translucency increases, almost to the point of complete transparency.

"Glass frogs are well known for their highly transparent muscles and ventral skin, through which their bones and other organs are visible," Taboada and colleagues write in their paper.

"We found that these tissues transmit more than 90 to 95 percent of visible light while maintaining functionality [such as] locomotion [and] vocalization. This transparency is adaptive because it camouflages glass frogs from predators while they sleep on vegetation during the day."

This is curious, because red blood cells circulating throughout the body can render even transparent tissues opaque. Transparency is also extremely rare in land animals, making glass frogs an exception worth studying. So Taboada decided to study the frogs to figure out their curious trick.

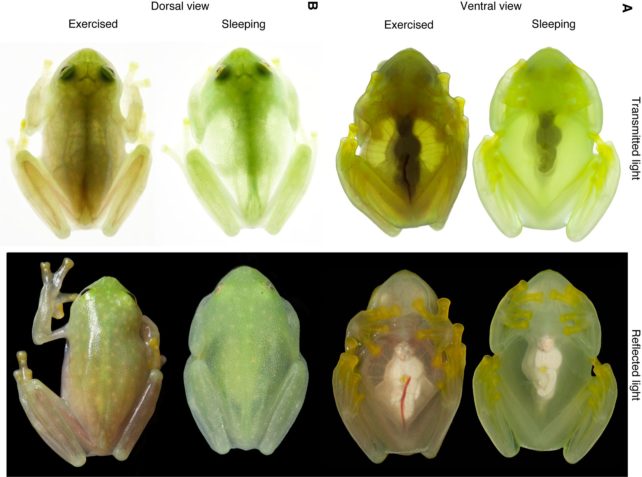

They took 11 Fleischmann's glass frogs, and used calibrated color photography to repeatedly measure their transparency at different times: while sleeping, while awake, calling to mates, after exercise, and under anesthetic.

The researchers found that the frogs maintained roughly the same level of transparency while awake, calling, exercising, and under anesthetic.

However, when they were sleeping, the frogs were between 34 and 61 percent more transparent than during waking activity.

Optical spectroscopy on 13 frogs confirmed that a decrease in circulating red blood cells is the reason for the increased transparency on their undersides. Red blood circulation decreased by up to 89 percent, and the red blood cell signal was concentrated in the liver.

In order to sleep safely, the frogs sequester most of their red blood cells in their liver. When they wake up, red blood cells start circulating normally, and they can go about their normal activity, having suffered no obvious ill effects. It's quite marvelous.

"The primary result is that whenever glassfrogs want to be transparent, which is typically when they're at rest and vulnerable to predation, they filter nearly all the red blood cells out of their blood and hide them in a mirror-coated liver – somehow avoiding creating a huge blood clot in the process," says one of the researchers, Sönke Johnsen, a professor of biology at Duke University.

"Whenever the frogs need to become active again, they bring the cells back into the blood stream, which gives them the metabolic capacity to move around."

It's unknown how the glass frogs do this, and whether it can be a voluntary response to other situations, such as a threatening predator. It's also unclear if the frogs have some sort of special metabolic adaptation that allows them to experience dramatic changes in circulation without damaging their other organs.

But the ability to stash red blood cells in the liver while sleeping is not unique to Fleischmann's glass frog, according to the researchers. They studied three species of tropical opaque tree frogs, and found that their circulating red blood cells decreased by 12 percent while sleeping.

But the discovery that a vertebrate animal can actively remove nearly 90 percent of its blood from circulation while sleeping, and then restore it, has some interesting implications for human health. The fact that they manage to do this on a daily basis without the blood clotting means that their blood cells may have some modifications that act against clotting while the blood is being packed and unpacked, which could help scientists develop new interventions to prevent thrombosis and stroke.

"Finally, these naturally transparent vertebrates are an excellent animal for in vivo physiology research. Their entire body can be imaged with cellular resolution to capture natural hemodynamic processes without restraint or contrast agents," the researchers conclude.

"Glass frogs' ability to regulate the location, density, and packing of red blood cells without clotting offers insight in metabolic, hemodynamic, and blood-clot research."

The research has been published in Science.