Nearly 2,000 years ago, when Rome was at its peak, a volcano erupted on New Zealand's North Island with such violence it was thought to have cast a pall over the empire's lands half a world away.

Scientists have now unearthed six glass shards traced to the heat of the explosion, flung 5,000 kilometers (3,100 miles) south where they lay buried beneath 280 meters of Antarctic ice for some 2,000 years.

A seventh shard, formed from an earlier eruption of the same volcano, helped the team pinpoint their exact origins, and helped confirm the timing of the explosive event.

"Combined, the seven shards provide a unique and undeniable double fingerprint of the Taupō volcano as the source," says environmental scientist Stephen Piva, the study's lead author and a PhD candidate at Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington.

The Taupō volcano has been active for about 300,000 years, but the timing of its most recent major eruption – one of the largest and most energetic eruptions on Earth in the past 5,000 years – has been surprisingly hard to pin down.

Historical records from ancient Rome and China describing events around 186 CE suggest a distant volcanic eruption clouded their skies, half a world away: the Sun rose "red as blood and lacking light" and "the heavens were ablaze", two scribes wrote.

Vivid as those descriptions might be, they don't quite line up with the geological record. Sulfur deposits in ice cores are the usual signal of volcanic activity, and ice cores from Antarctica and Greenland narrowed the timing of the Taupō eruption to around 230 CE, give or take a few decades.

Sulfur is ejected from volcanoes all over the world though, so it's not nearly as precise as scientists would like. Radiocarbon dates of tree logs entombed in hot volcanic flows from the Taupō eruption refined its timing to around 232 CE (1,790 years ago). Fruits and seeds on those preserved trees, and their lack of darker, outer latewood, suggested the volcano blew its top in late summer or autumn, but the year of the eruption was still disputed.

So Piva and colleagues turned to an ice core 764 meters long, extracted from the Ross Ice Sheet in West Antarctica and packed with some 83,000 years of climate information.

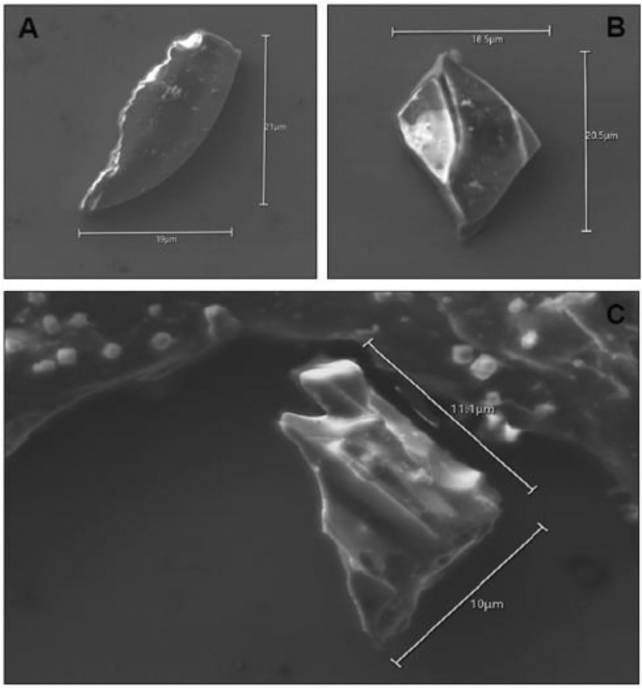

At a depth of 279 meters the researchers found seven glass shards about 10 to 20 microns long and made of the granite-like mineral rhyolite.

Their geochemical make-up matched other samples from the Taupō eruption, collected in New Zealand. One shard in particular stood out: it was a match for volcanic glass produced by the earlier Ōruanui supereruption of the Taupō volcano, which occurred 25,600 years ago.

This 'double fingerprint' of Taupō gave the researchers extra confidence as to the glass shards' source, while their position in the ice core was dated to the early months of a year close to 230 CE.

The Ōruanui glass, being centuries older but made of the same material, was likely unearthed from the Taupō volcano and expelled into the stratosphere along with the newly formed glass shards of the 230 CE eruption.

"A massive eruption plume would have sent a huge volume of volcanic particles into the air where they would have been widely dispersed by the wind," explains Piva.

While there is still some margin of error with ice core dating, the researchers say their findings validate the age estimate of the buried tree logs, which likely died in an instant when engulfed by the Taupō volcano's blistering hot ejecta.

"Confirming the eruption date provides an opportunity to study the volcano's potential global effects on the atmosphere and climate, which is crucial for better understanding its eruptive history and behavior," Piva says.

The study has been published in Scientific Reports.