If you were to host a blacklight party in the taxidermy wing of a natural history museum, most of the mammals would fit right in with their eerie fluorescent glow.

That's what Kenny Travouillon, the curator of mammalogy at the Western Australian Museum, found when his team shone ultraviolet light on 125 species of mammal in the collection.

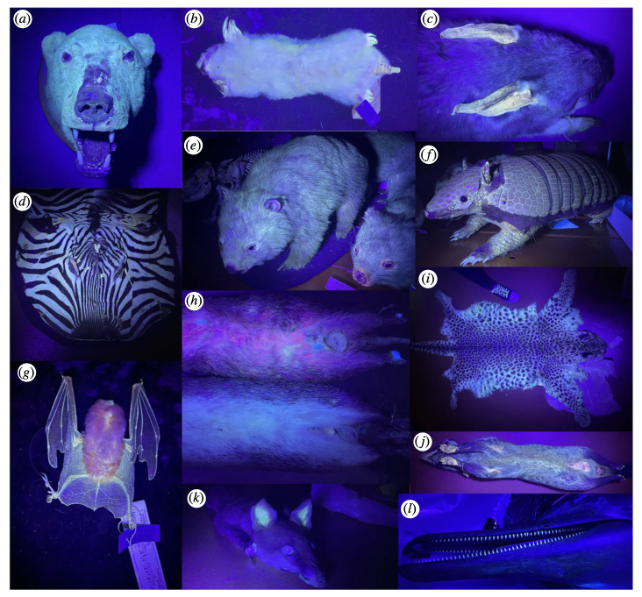

The luminous effect wasn't restricted to platypuses and wombats, which were identified as biofluorescent species a few years ago. Every species of mammal they examined emitted a green, blue, pink, or white hue under UV light.

The inside of a red fox's pointy ears turned shocking, fluorescent green.

The polar bear lit up like a white t-shirt under a blacklight, as did the zebra's white stripes and the leopard's yellow fur.

The wings of the orange leaf-nosed bat became a stark white skeleton, while its fur glowed pink.

And the ears and tail of the greater bilby shone "bright like a diamond," as Travouillon described in 2020.

The study showed that fluorescence is present in half of mammalian families, almost all clades, and in all 27 orders.

"We found that fluorescence is widespread in mammalian taxa," the researchers write. "Areas of fluorescence included white and light fur, quills, whiskers, claws, teeth and some naked skin."

The only species of mammal that had no external fluorescence was the dwarf spinner dolphin; only its teeth were fluorescent.

Fluorescence is created when a chemical, such as a protein, absorbs ultraviolet light and then emits a longer wavelength of light.

It's been observed in coral, sea turtles, frogs, scorpions, New World flying squirrels, parrots, rabbits, humans, and dormice.

Biologists have long debated whether this fluorescent glow confers an evolutionary advantage or is simply a by-product of surface chemistry.

"It remains unclear if fluorescence has any specific biological role for mammals," the researchers write.

A protein called keratin found in nails, skin, teeth, bone, quills, whiskers, and claws is biofluorescent, but this optical property could just be an accident of evolution. Keratin also causes fluorescence in unpigmented or pale-colored hair.

The southern marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops) was one of the most fluorescent mammals due to its yellow-white fur. But this species lives underground.

The keratin in N. typhlops' fur may be heightened to protect against abrasive soil particles, with fluorescence as a side effect, the researchers hypothesize.

Similarly, fluorescence in bats that use echolocation instead of sight to navigate and hunt seems unlikely to promote survival.

Despite much skepticism, there was some evidence that fluorescence was evolutionarily advantageous in some mammals.

When the researchers saw fluorescence in pigmented fur, this suggested that a chemical other than keratin was creating the effect, such as fluorophores.

Mammals that are most active at night, dusk, or dawn could be using fluorescence to become more visible in low-light conditions to mate or defend territory.

"Fluorescence was most common and most intense among nocturnal species," the team writes.

Platypuses close their eyes underwater to hunt, so it's unlikely that their glowing belly fur is a useful visual cue.

However, this could be a form of camouflage called countershading, which is seen in many aquatic animals.

Or perhaps the platypus absorbs UV light instead of reflecting it in order to hide from predators and prey whose eyes can perceive this wavelength of light.

Evolutionary advantage or not, it's a fascinating phenomenon!

This research was published in Royal Society Open Science.