Seventy-nine thousand tons of plastic debris, in the form of 1.8 trillion pieces, now occupy an area three times the size of France in the Pacific Ocean between California and Hawaii, a scientific team reported on Thursday.

The amount of plastic found in this area, known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, is "increasing exponentially," according to the surveyors, who used two planes and 18 boats to assess the ocean pollution.

"We wanted to have a clear, precise picture of what the patch looked like," said Laurent Lebreton, the lead oceanographer for the Ocean Cleanup Foundation and the lead author of the study.

The Garbage Patch has been described before. But this new survey estimates that the mass of plastic contained there is four to 16 times larger than previously supposed, and it is continuing to accumulate because of ocean currents and careless humans both onshore and offshore.

The "patch" is not an island or a single mass, leading some scientists to object to the name (which the current study uses).

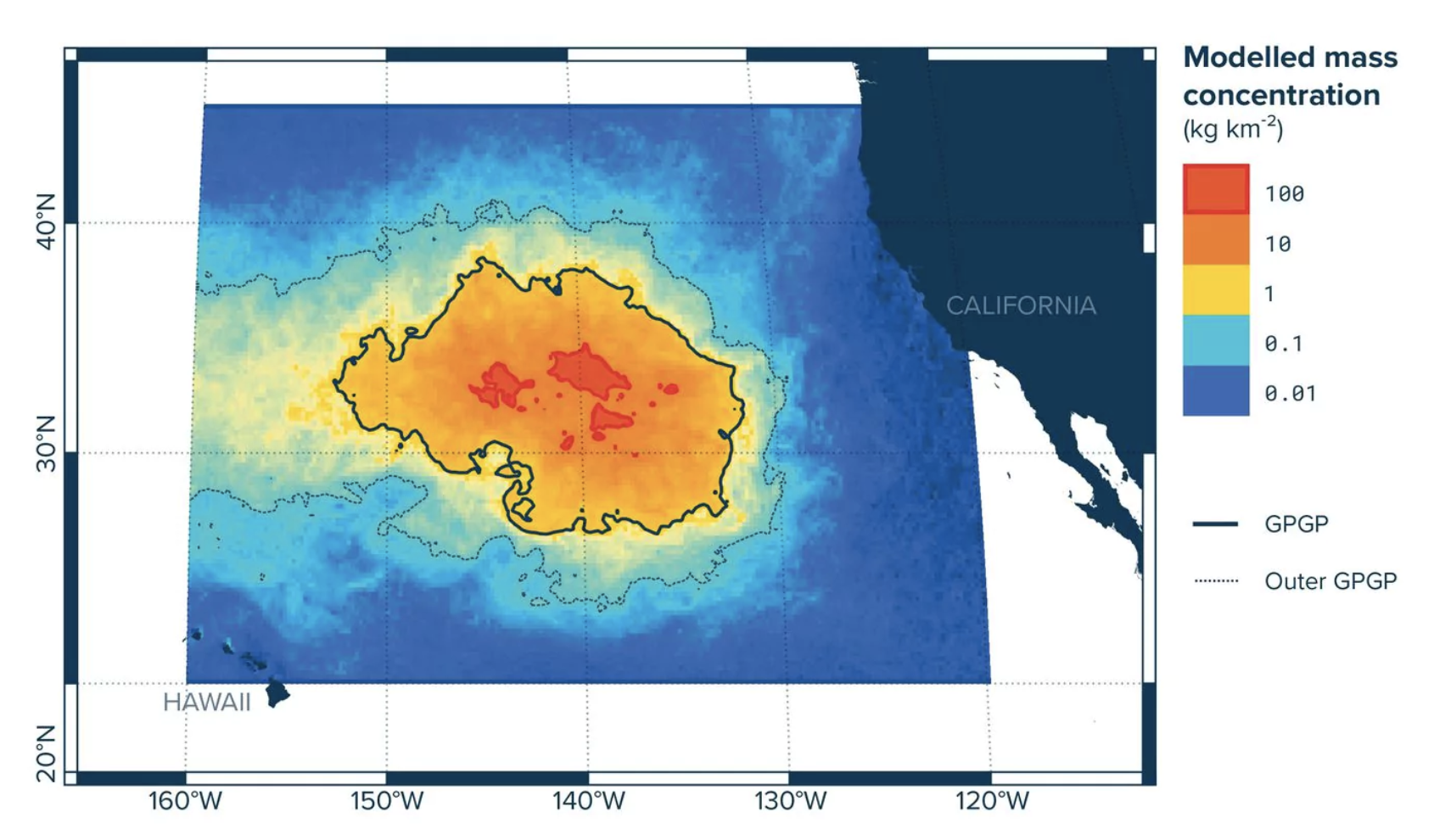

Instead, it's a large area with high volumes of plastics, one in which concentrations increase markedly as you move toward its center. The debris ranges from tiny flecks to enormous discarded fishing nets, which make up 46 percent of the material, the study found.

The study was led by the Ocean Cleanup Foundation and researchers at institutions in New Zealand, the United States, Britain, France, Germany and Denmark, who published the findings in the journal Scientific Reports.

The Ocean Cleanup Foundation released this image showing the size of the patch and also where the plastic becomes most dense:

Ocean Cleanup Foundation

Ocean Cleanup Foundation

There's a key distinction between the mass of plastic within the patch increasing — which it is — and the overall size of the patch, which does not seem to be changing.

Rather, it's just that trash within the patch seems to be accumulating, or growing more dense.

The plastic is probably mostly coming from Pacific countries, Lebreton said.

But it could be coming from anywhere since plastic now travels across the entirety of the ocean and has even shown up in Arctic waters, where very few humans live. That suggests the plastic traveled there from elsewhere, riding the ocean currents.

Some of the debris probably also came from the 2011 tsunami that devastated Japan and washed large amounts of waste back out to sea, the study said.

The location of the patch is in a zone of slack currents where debris arrives and then lingers, increasing in the calm waters.

The study finds that, based on prior examinations dating back to the 1970s, the amount of plastic in the patch is steadily growing as more flows in than flows out — saying that plastic levels are "increasing exponentially."

"We think there's more and more plastic basically accumulating in this area," Lebreton said.

The most striking aspect of the findings — and perhaps the most damaging — was the large volume of fishing nets or "ghostnets," said Chelsea Rochman, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto who studies marine plastic but was not part of the current study.

"This suggests we might be underestimating how much fishing debris is floating in the oceans," she said in an emailed comment.

" Entanglement and smothering from nets is one of the most detrimental observed effects we see in nature."

The fact that the plastic content of the Patch is increasing is consistent with research that has been conducted on land, showing that waste volumes entering the ocean are large and increasing, said Jenna Jambeck, an environmental engineer at the University of Georgia who has studied plastic waste processes.

In a 2015 study, Jambeck found that humans are filling the oceans with an estimated 8 million tons of plastic every year, and that is expected to increase 22 percent by 2025.

That matches what is now being seen in the ocean, in the form of an ever-accumulating garbage patch in the Pacific, though Jambeck also noted that much plastic sinks to the ocean bottom, and the fishing nets are being tossed in from boats, rather than dumped from the shore.

"The logic plays out that if we projected it to be increasing, every year in terms of input, that you would see some potential increase in the ocean," Jambeck said. She also was not involved in the new study.

Jambeck and the research team both agree that there is far less plastic accumulating in the Pacific patch than is going in the ocean — and the study itself says that in light of how much plastic is being dumped, they would have expected volumes to be even higher.

Clearly, much plastic is sinking and doing its damage at the seafloor, or in lower depths of the ocean.

In this sense, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is, in the end, merely the most dramatic outward symptom of a far deeper problem of enormous volumes of human waste reaching places where it was never intended to be.

"The results are alarming; it really shows the urgency of this situation," Lebreton said.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.