When one thinks of Greenland, images of an icebound, harsh and forbidding landscape probably come to mind, not a landscape of ice pocked with melt ponds and streams transformed into raging rivers. And almost certainly not one that features wildfires.

Yet the latter description is exactly what Greenland looks like today, according to imagery shared on social media, scientists on the ground and data from satellites.

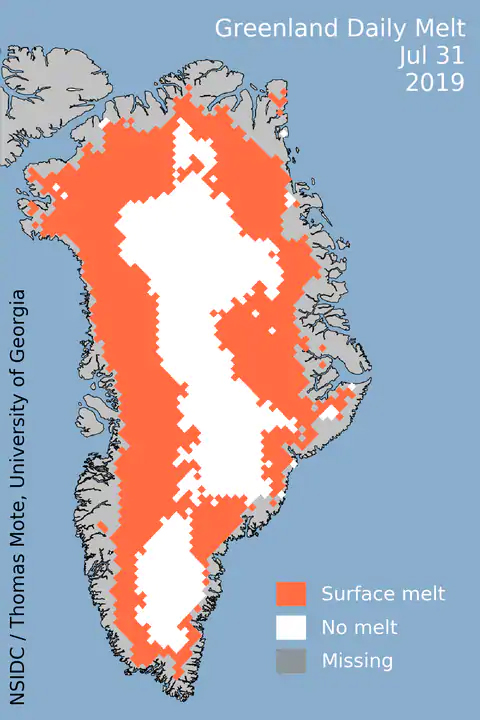

An extraordinary melt event that began earlier this week continues on Thursday on the Greenland ice sheet, and there are signs that about 60 percent of the expansive ice cover has seen detectable surface melting, including at higher elevations that only rarely see temperatures climb above freezing.

July 31 was the biggest melt day since at least 2012, with about 60 percent of the ice sheet seeing at least 1 millimeter of melt at the surface, and more than 10 billion tons of ice lost to the ocean from surface melt, according to data from the Polar Portal, a website run by Danish polar research institutions, and the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Thursday could be another significant melt day, before temperatures drop to more seasonable levels.

According to Ruth Mottram, a climate researcher with the Danish Meteorological Institute, the ice sheet sent 197 billion tons of water pouring into the Atlantic Ocean during July.

This is enough to raise sea levels by 0.5 millimeter, or 0.02 inches, in a one-month time frame, said Martin Stendel, a researcher with the institute.

For those keeping track, this means the #Greenland #icesheet ends July with a net mass loss of 197 Gigatonnes since the 1st of the month. https://t.co/Qgwj6WtUzF

— Ruth Mottram (@ruth_mottram) August 1, 2019

This might seem inconsequential, but every increment of sea-level rise provides a higher launchpad for storms to more easily flood coastal infrastructure, such as New York's subway system, parts of which flooded during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Think of a basketball game being played on a court whose floor is gradually rising, making it easier for even shorter players to dunk the ball.

As a result of both surface melting and a lack of snow on the ice sheet this summer, "this is the year Greenland is contributing most to sea-level rise," said Marco Tedesco, a climate scientist at Columbia University.

Thanks to an expansive area of high pressure enveloping all of Greenland - the same weather system that brought extreme heat to Europe last week - temperatures in Greenland have been running up to 15 to 30 degrees above average this week.

At Summit Station, which at 10,551 feet (3,215 metres) is located at the highest point in Greenland and rarely sees temperatures above freezing, the thermometer exceeded this mark for about 11 hours Tuesday, according to Christopher Shuman, a glaciologist at the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

(National Snow and Ice Data Center)

(National Snow and Ice Data Center)

The ongoing melt event is being compared to a record extreme heat and melt episode that occurred in Greenland in 2012. While the extent of surface melt during that event may have exceeded this one so far, Shuman found that Summit Station experienced warmth that was greater "in both magnitude and duration" during the current event.

The temperature only remained above freezing about half as long in 2012, and the peak temperature reached 34.02 degrees Fahrenheit (1.12 Celsius) this year, whereas it only hit 33.73 Fahrenheit (0.96 Celsius) in 2012. During the 2012 extreme event, however, 97 percent of the ice surface experienced melting.

"Like 2012, this melt event reached the highest elevations of the ice sheet, which is highly unusual," says Thomas Mote, a professor of geography at the University of Georgia. "Both our satellite observations and the ground-based observations from Summit indicated melt on Tuesday."

"The event itself was unusual that the warm air mass came from the east, and appears to be a part of the air mass that caused the record-breaking heat wave in Europe. Most of our extreme melt days on the Greenland ice sheet are associated with warm air masses moving from the west and south. I cannot recall an instance where we saw such extensive melt associated with an air mass coming from Northern Europe," Mote said.

The heat, along with below-average precipitation in parts of Greenland, has even sparked wildfires along the Greenland's non-ice-covered western fringes. Satellite images and photos taken from the ground show fires burning in treeless areas, consuming mossy wetlands known as fen that can become vulnerable to fires when they dry out.

These fires can burn into peatlands, releasing greenhouse gases buried long ago through decomposition of organic matter.

Studies have shown that ice melt periods like the one seen in 2012 typically occur about every 250 years, so the fact that another one is taking place only a few years later could be a sign of how climate change is upping the odds of such events.

According to DMI's Mottram, the short-term, extreme melt event is a sign of climate change's increasing influence on the Arctic.

"So yes it's weather but it shows that in spite of internal variability the background signal of a warming climate is still 'winning'," she said via a Twitter message.

She said state-of-the-art climate computer models have been unable to simulate events like this, which hampers scientists' ability to accurately predict Greenland ice melt and, therefore, future sea-level rise.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.