Ice is melting in unprecedented ways as summer approaches in the Arctic. In recent days, observations have revealed a record-challenging melt event over the Greenland ice sheet, while the extent of ice over the Arctic Ocean has never been this low in mid-June during the age of weather satellites.

Greenland saw temperatures soar up to 40 degrees Fahrenheit above normal Wednesday, while open water exists in places north of Alaska where it seldom, if ever, has in recent times.

It's "another series of extreme events consistent with the long-term trend of a warming, changing Arctic," said Zachary Labe, a climate researcher at the University of California at Irvine.

And the abnormal warmth and melting of ice in the Arctic may be messing with our weather.

Greenland ice sheet

(National Snow and Ice Data Center)

(National Snow and Ice Data Center)

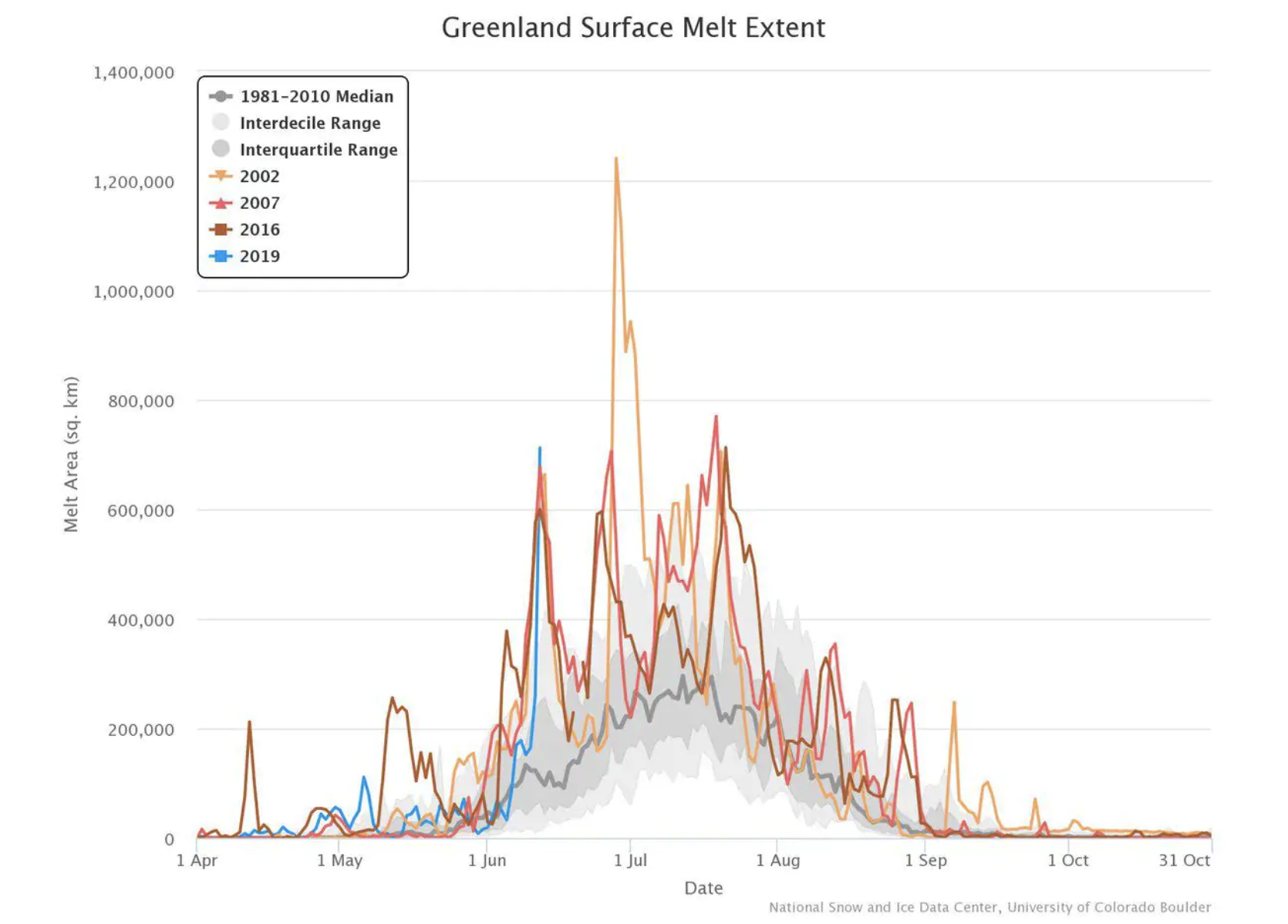

Above: Melt extent on the Greenland Ice Sheet between April and October. The recent melt event (indicated by the blue line) appears to be the greatest on record in mid-June.

Data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center show that the Greenland ice sheet appears to have witnessed its biggest melt event so early in the season on record this week (although a few other years showed similar mid-June melting).

"The melting is big and early," said Jason Box, an ice climatologist at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland.

Box explained that temperatures over the western Greenland ice sheet have been abnormally high while snow has been well below normal.

Marco Tedesco, an ice researcher at Columbia University, added that it has been unusually warm in east and central Greenland, as well. "This has triggered widespread melting that has reached about 45 percent of the ice sheet," he wrote in an email.

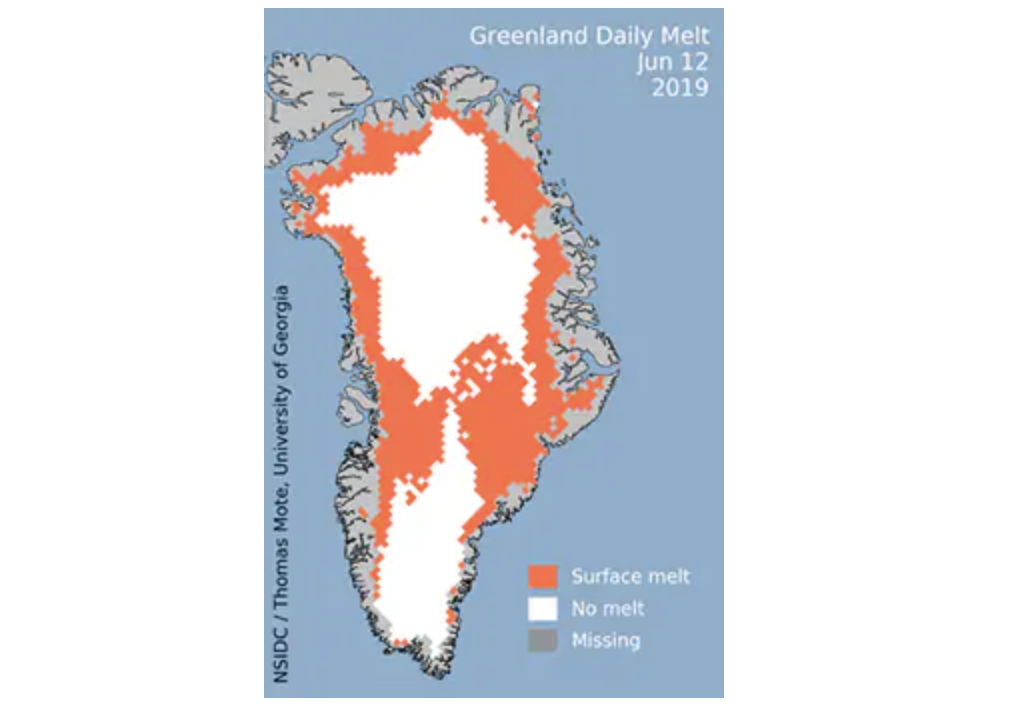

Extent of Greenland ice sheet melting on June 12. (National Snow and Ice Data Center)

Extent of Greenland ice sheet melting on June 12. (National Snow and Ice Data Center)

Normally, melting this widespread over the ice sheet doesn't occur until midsummer, if even then.

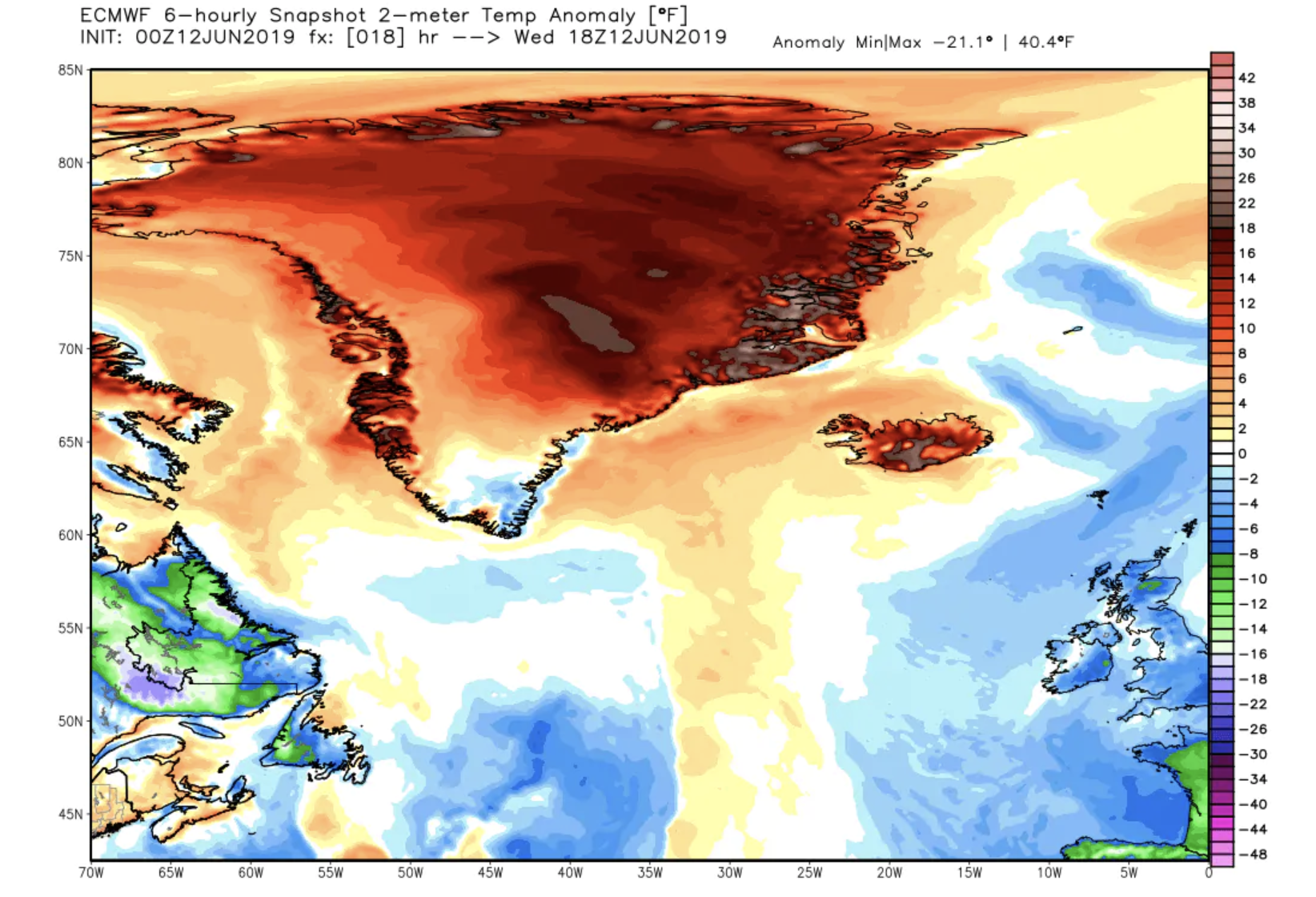

A simulation from the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasting suggested that temperatures over Greenland may have peaked at around 40 degrees above normal on Wednesday.

(WeatherBell.com)

(WeatherBell.com)

Above: European model simulation of temperature difference from normal over Greenland on Wednesday.

A big dome of high pressure has positioned itself over Greenland, resulting in sunny skies and mild temperatures, which have enabled melting. An automated weather station at the top of Greenland's ice sheet topped freezing on June 12, a very rare event, which last occurred in July 2012.

The @NOAA automatic weather station at Summit, Greenland, suggests air temperature flickered above 0°C at 19:30 LST June 12. 🤔https://t.co/Dy0e7uRiRx pic.twitter.com/EpOl2R5dmV

— William Colgan, Ph.D. (@GlacierBytes) June 13, 2019

2012 is the notorious year in which the Greenland ice sheet witnessed the most melting on record. Those monitoring the ice sheet say melting in 2019 could rival it.

Weather in the coming months will determine how much more the ice sheet melts and whether 2019 is a record-setter. If high pressure holds in place, "we should break a new record," tweeted Xavier Fettweis, a climatologist at the University of Liège in Belgium.

But scientists studying the region know that Greenland's weather is highly variable and can change rapidly.

Mike MacFerrin, a glaciologist at the University of Colorado, put it this way in a tweet: "2019 has been… anomalous… so far, but also quite variable. It's early and weather is weather, so keep your eyes peeled. …"

Arctic sea ice

(Zachary Labe)

(Zachary Labe)

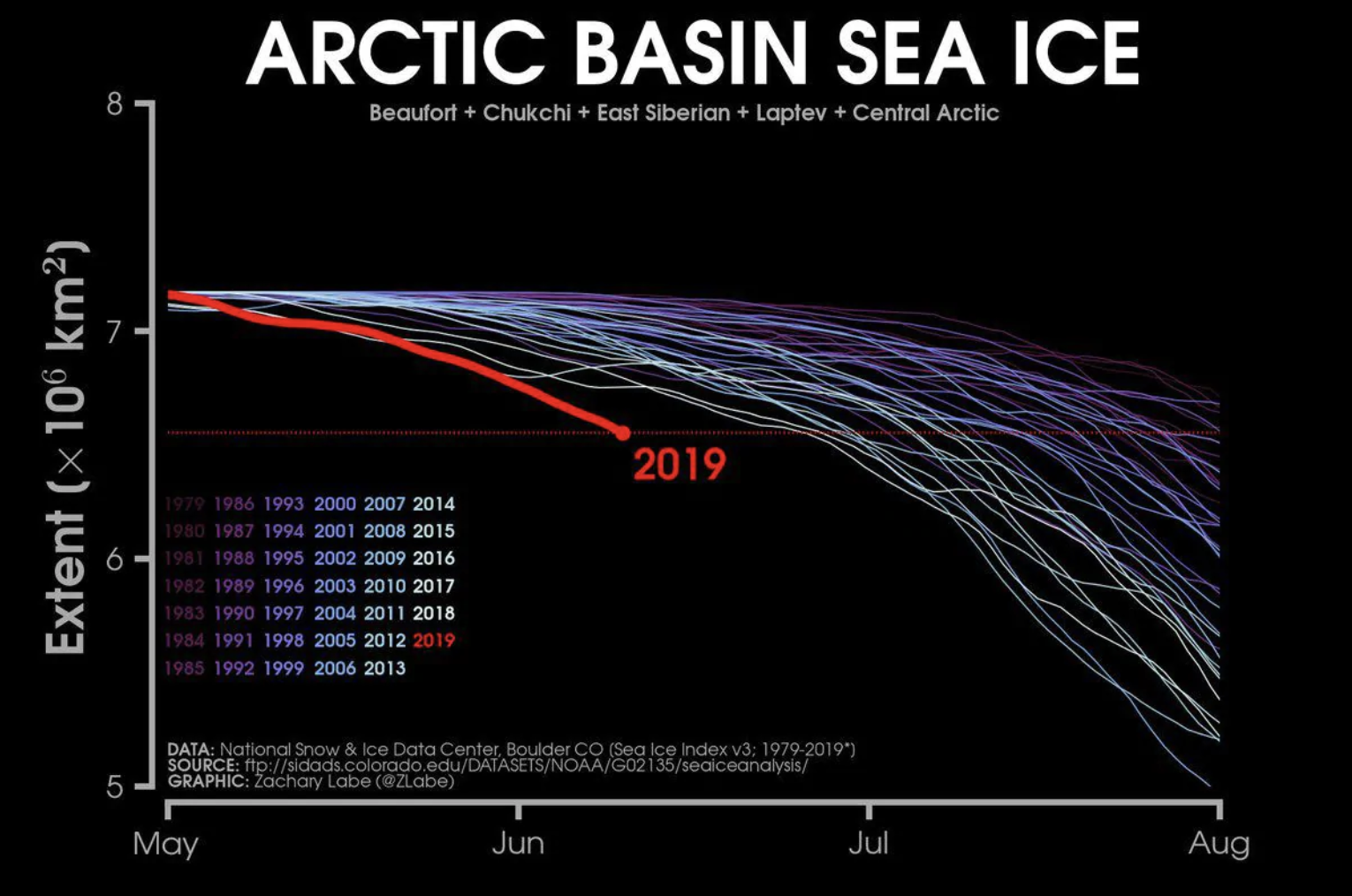

Weather satellites have monitored sea ice in the Arctic since 1979, and the current ice coverage is the lowest on record for mid-June.

The ice extent has been especially depleted in the part of the Arctic Ocean adjacent to the Pacific Ocean. "It's pretty remarkable how much open water is in that area," Labe said.

Labe explained high pressure over the Arctic has helped to pull sea ice way from the northern Alaska coast.

Sea ice loss over the Chukchi and Beaufort seas along Alaska's northern coast has been "unprecedented" according to Rick Thoman, a climatologist based in Fairbanks.

Labe said there's sufficient open water that you could sail all the way from the Bering Strait into a narrow opening just north of Utqiagvik, Alaska's northernmost city, clear into the Beaufort Sea. "It's very unusual for open water this early in this location," he said.

With all of the exposed water, ocean temperatures in this region will rise, Labe said. This should delay the customary fall freeze and will likely result in a historically low late summer sea ice minimum, typically in mid-September.

Whether the Arctic sea ice minimum is record-setting, like the Greenland ice sheet, will depend on weather in the coming months.

"There is no indication that this year will be as low as 2012," when Arctic sea ice reached its lowest extent on record, Labe said. "If cloudy weather occurs, it would slow down the rate [of melting]. It's really hard to predict."

Implications for weather over the United States?

The extreme conditions in the Arctic, which have resulted in these record-challenging melt events, have far-reaching implications. There is a saying often repeated by Arctic researchers: "What happens in the Arctic doesn't stay in the Arctic."

The bulging zones of high pressure in the Arctic, which have facilitated the unusual warmth and intensified melting, are displacing the cold air normally contained in that region into the mid-latitudes — like a refrigerator door left open. Much of the central and eastern United States have seen lower-than-normal temperatures in the past week.

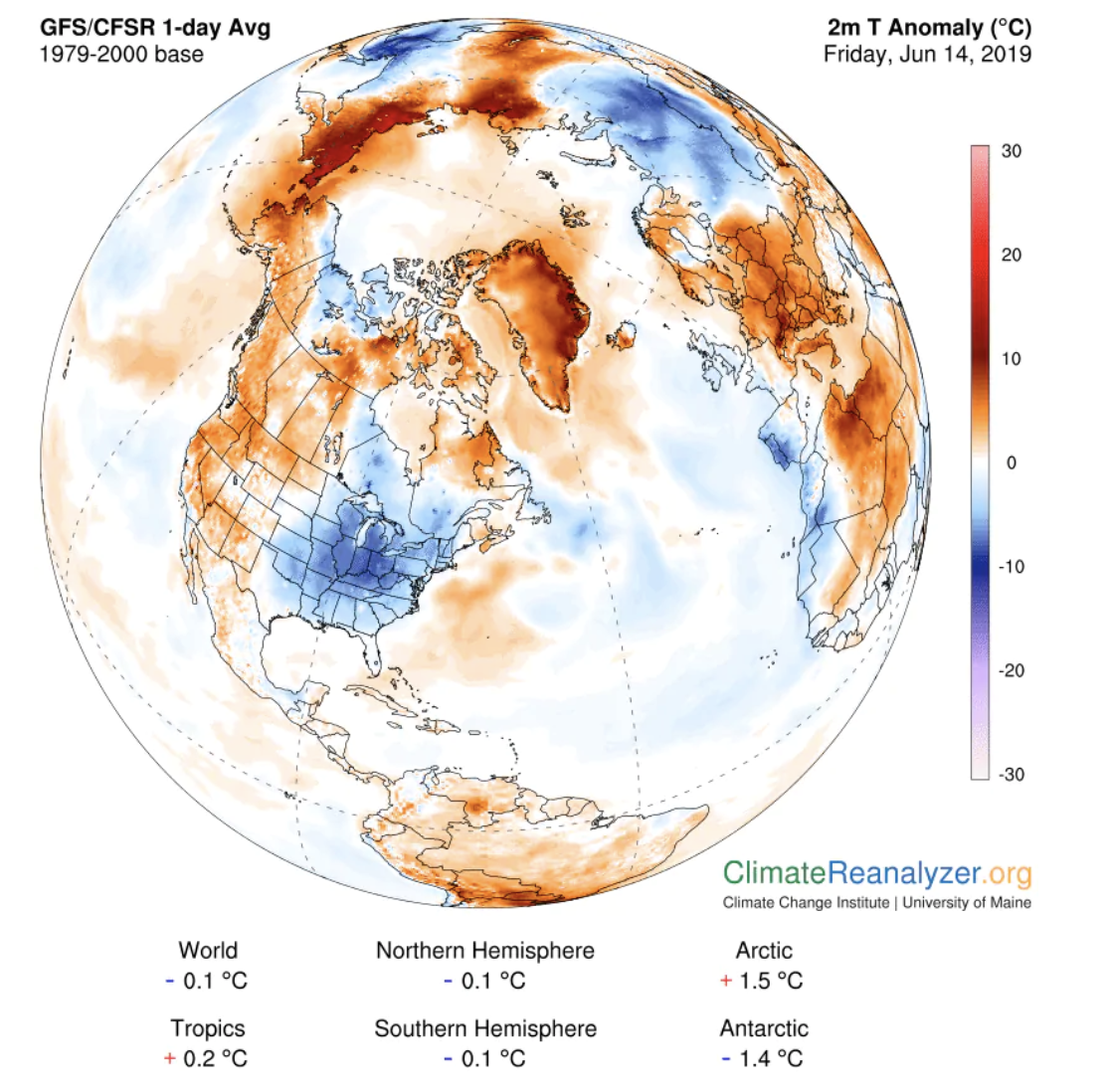

(University of Maine Climate Reanalyzer)

(University of Maine Climate Reanalyzer)

Above: Temperature difference from normal on Friday, as analyzed by the Global Forecast System model.

The jet stream, the high-altitude current separating cold air and warm air, has taken unusually erratic meanders.

"The jet stream this week was one of the craziest I've ever seen!" Jennifer Francis, one of the leading researchers who has published studies connecting Arctic change and mid-latitude weather, wrote in an email.

Francis had earlier suggested that conditions in the Arctic may have played a role in the extreme jet stream pattern that spurred the tornado swarm and record flooding in the central US during the last two weeks of May.

"We can't say that the rapid Arctic warming is causing this particularly pattern, but it certainly is consistent with that," Francis, senior scientist at Woods Hole Research Center, said.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.