More treatments – and faster-acting treatments – for peanut allergies are urgently needed, and a new study outlines a promising drug technology based around a tiny nanoparticle just a few billionths of a meter in size.

In tests on mice, the nanoparticle reversed peanut allergies and prevented them from developing in the first place. If the same response is triggered in humans, it could change the lives of millions of people.

At the center of the treatment is a protein fragment called an epitope; it's specially designed as an antigen (a substance intended to trigger a response from the immune system) that leaves out the part of the protein that normally causes the allergic reaction.

The idea is that exposure to a modified version of the allergen helps train the body against the full force of the actual substance – in this case, peanuts.

"If you're lucky enough to choose the correct epitope, there's an immune mechanism that puts a damper on reactions to all of the other fragments," says André Nel, an immunologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. "That way, you could take care of a whole ensemble of epitopes that play a role in disease."

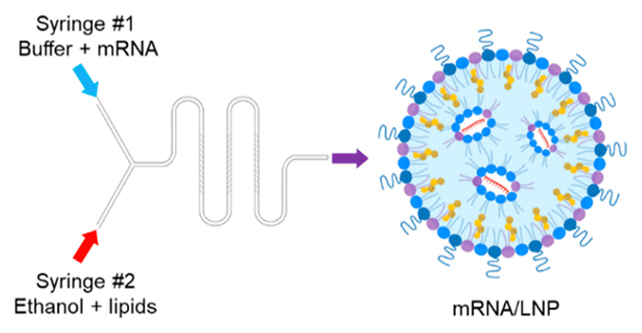

The same technique was used in earlier studies, but in this experiment, researchers added some extra ingredients: a sugar molecule that binds to antigen-fighting immune cells and the use of the biological messenger mRNA to build instructions into the epitope.

By adding the mRNA element, the researchers could more easily load up the nanoparticle and fit it with multiple epitopes. The same approach is used in COVID-19 vaccines, where the entire spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 gets encoded to produce immunity.

Once built, the researchers aimed the nanoparticles at the liver. The organ doesn't overreact to every foreign substance it encounters, and it is where antigen-presenting cells live, the cells that train the body not to produce an excessive allergic reaction in self-defense.

"As far as we can find, mRNA has never been used for an allergic disease," says Nel.

In a series of experiments with mice, the nanoparticles were shown to reduce the allergic reaction to peanuts and increase the production of substances in the body that should build up a tolerance to peanuts in the future.

Those substances included antibodies, cytokines (proteins crucial in the immune response), and enzymes (proteins driving particular chemical reactions in the body). The benefits of the nanoparticle held whether or not the mice were sensitized to peanut allergens beforehand.

Thanks to the mRNA design of the treatment, the drug can be adapted for other allergies and autoimmune disorders, the researchers say. It might also help treat type 1 diabetes, which also involves a harmful reaction from the immune system.

The team says it could take three years before clinical trials with humans can get underway, depending on how well further lab research goes. But with peanut allergies now affecting at least 4.6 million adults and 1.6 million children, these nanoparticles have a lot of potential to help people.

"We've shown that our platform can work to calm peanut allergies, and we believe it may be able to do the same for other allergens, in food and drugs, as well as autoimmune conditions," says Nel.

The research has been published in ACS Nano.