Four patients with severe chemical burns to one eye have shown early positive results in a phase 1 clinical trial of a therapy based on their own stem cells.

Even without further treatment, two of the patients reported significant improvements in their vision after a year of follow-up, according to a team of US researchers. The other two patients were able to undergo corneal transplants, which had previously not been an option due to the severity of their injuries.

"Our early results suggest [the treatment] might offer hope to patients who had been left with untreatable vision loss and pain associated with major cornea injuries," says lead study author Ula Jurkunas, an ophthalmologist from Massachusetts Eye and Ear.

The new technique develops a tissue graft from a small biopsy of stem cells taken from the patient's healthy eye. Called cultivated autologous limbal epithelial cell (CALEC) transplantation, it doesn't carry the risk of rejection like some other procedures because the cells are taken from the patient's own body.

Cells for CALEC transplantation are harvested from the healthy eye's limbus, the outer corneal border. These limbal stem cells play a role in preserving the cornea, the protective, transparent outer layer of the eye that light goes through first. Its smoothness is essential to clear vision.

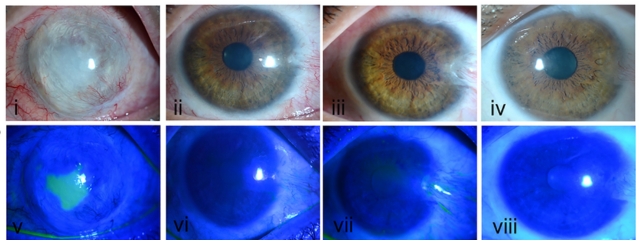

Patients with chemical burns to their eye frequently have permanent damage to the limbal area, making it impossible for new cells to regenerate normally.

Treatments for eye damage typically involve transplanting a healthy cornea from a donor eye. Since functional limbal stem cells and a healthy eye surface are needed to support the new corneal tissue, transplants aren't an option for individuals with significant damage.

Alternative methods include donor limbal tissue grafts, which can cause infection, or transplanting a larger portion of the patient's healthy eye cells directly to the injured eye. Removing that much tissue can damage limbal cell growth in the healthy eye, which doesn't seem like a useful compromise.

This new approach uses a minimal amount of the healthy eye's stem cell tissue, which is grown into a larger layer of cells that can facilitate the regeneration of healthy tissue once transplanted on the injured eye's surface.

Once a healthy surface has been restored, these patients are able to receive a conventional corneal transplant, which some of those in the phase 1 trial didn't need.

The four treated patients were males aged between 31 and 52 years. After CALEC transplantation, one didn't experience improved vision, but his eye surface healed, clearing the way for him to get a cornea transplant.

In another, an initial biopsy failed to produce a viable stem cell graft, but he had a successful transplant three years later on a second attempt at CALEC. His vision improved from depicting hand motion to being able to count fingers, and he too became able to receive a cornea transplant.

Incredibly, the other two patients had significant improvement to 20/30 vision, enough to not need a corneal transplant at all.

Biopsies were taken from the healthy eyes of five patients, although one was unable to undergo CALEC transplantation as the stem cells didn't expand. Importantly for the procedure's short-term feasibility and safety, all five patients' biopsied eyes healed without complications, and vision returned within 4 weeks.

The lack of high-safety treatment options for patients with chemical burns and other injuries that prevent them from receiving a cornea transplant has hampered cornea specialists, according to Jurkunas.

Researchers are currently finishing up the next phase of the clinical trial in CALEC patients, whom they have been following for 18 months, to better determine the overall efficacy of the procedure.

"We are hopeful with further study, CALEC can one day fill this crucially needed treatment gap," Jurkunas says.

The study has been published in Science Advances.