For much of the history of paleontology, scientists thought all dinosaurs were covered in scales, like the lizards of today.

That was until a spate of discoveries in recent decades revealed many of these marvelous extinct animals sported ancient feathers – just like their later descendants, birds.

As for pterosaurs – the flying reptiles that reigned in the sky when the dinosaurs roamed – the issue has never been settled. Were they bald? Did they have feathers too? Scant evidence in the fossil record has never been definitive – until now, scientists say.

Preserved on slabs of ancient limestone in north-eastern Brazil, a newly discovered fossil of Tupandactylus imperator reveals the existence of pterosaur feathers about 113 million years ago.

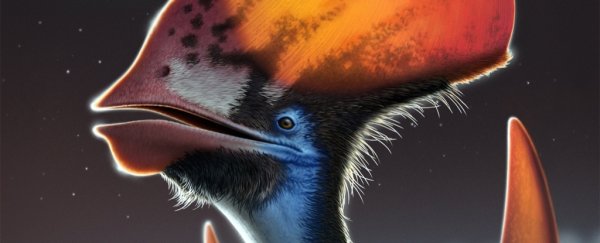

Artist reconstruction of Tupandactylus imperator. (Copyright Bob Nicholls 2022)

Artist reconstruction of Tupandactylus imperator. (Copyright Bob Nicholls 2022)

"We didn't expect to see this at all," says paleontologist Aude Cincotta from University College Cork in Ireland.

"For decades paleontologists have argued about whether pterosaurs had feathers. The feathers in our specimen close off that debate for good as they are very clearly branched all the way along their length, just like birds today."

Before now, researchers more or less agreed that pterosaurs were covered in an outer layer of filament-like structures called pycnofibers, which may have resembled a feathery fuzz, although whether they were the same thing as feathers was not known.

The new Brazilian specimen appears to clear that up, showing not only whisker-like single-stranded filaments sprouting from the creature's cranial crest, but also branched, distinctly feather-like structures that have not previously been reported in pterosaurs, marked by short fibers extending from a central shaft.

"This mode of branching is directly comparable to that in stage IIIA feathers of extant birds, that is, with barbs branching from a central rachis," the researchers write in a new paper describing the discovery.

"This is strong evidence that the fossil branched structures are feathers comprising a rachis and barbs."

Artist reconstruction of T. imperator, showing distinct feather types. (Copyright Bob Nicholls 2022)

Artist reconstruction of T. imperator, showing distinct feather types. (Copyright Bob Nicholls 2022)

According to the researchers' analysis, it's most likely that feathers were inherited from an avemetatarsalian ancestor common to both dinosaurs and pterosaurs, although it's also possible that these features evolved independently in different groups or species of animals.

Speaking of features, the faint traces of T. imperator's ancient plumage appear to have preserved a colorful secret kept hidden for many millions of years.

Examining the fossil with high-resolution electron microscopy, the researchers discovered the existence of abundant micro-bodies measuring approximately 0.5–1 μm in length in the animal's soft tissue, and interpreted to be melanosomes – organelles that hold melanin pigments responsible for different colors in animals' bodies.

The melanosomes had different kinds of shapes (between the monofilaments, branched feathers, and other cranial tissue), suggesting the pterosaur might have showed a range of colors across its plumage.

"In modern birds and mammals, many of the dominant colors of feathers and hair come from a limited range of chemically distinct forms of melanin," explains paleontologist Michael Benton from the University of Bristol in the UK, the author of an editorial commentary on the new findings.

Pterosaur melanosomes in electron micrograph images. (Cincotta et al., Nature, 2022)

Pterosaur melanosomes in electron micrograph images. (Cincotta et al., Nature, 2022)

While it's impossible to know for sure how T. imperator benefited from differently colored feathers over 100 million years ago, Benton says different colors on the pterosaur's prominent cranial crest may have contributed to signaling processes between different individuals, or to other attention-grabbing aspects of animal communication.

"Perhaps they were used in pre-mating rituals, just as certain birds use colorful tail fans, wings, and head crests to attract mates," he writes.

"Modern birds are renowned for the diversity and complexity of their colorful displays, and for the role of these aspects of sexual selection in bird evolution, and the same might be true for a wide array of extinct animals, including dinosaurs and pterosaurs."

The findings are reported in Nature.