Forecasters were closely watching Tropical Storm Idalia as it passed Cuba and headed toward exceptionally warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico. The storm was on track to intensify rapidly before making landfall on the Florida Panhandle, possibly as a major hurricane, on Wednesday, Aug. 30.

Hurricane scientist Haiyan Jiang of Florida International University explained the conflicting forces of unusually high ocean heat and wind shear, which typically accompanies El Niño climate patterns, that have made the 2023 hurricane season and even individual storms difficult to forecast.

What role is ocean temperature playing in Idalia's forecast?

Forecasters are watching several factors, but the biggest is the very high sea surface temperature in the Gulf of Mexico. The Gulf is typically warm in late August, and we often see hurricanes this time of year.

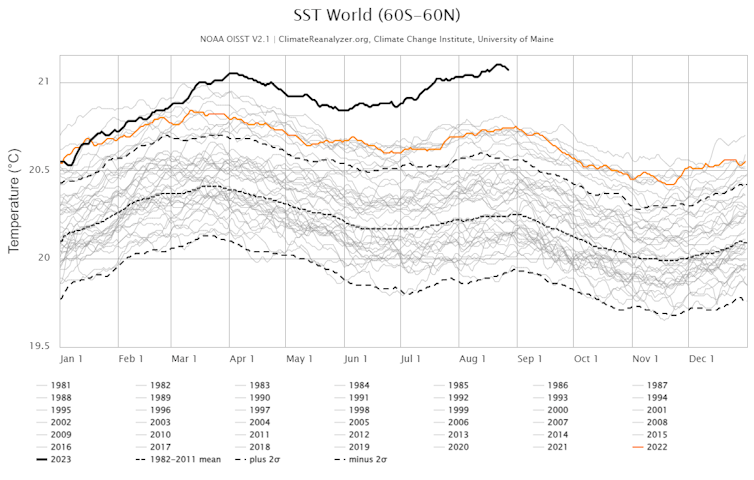

But this summer, the sea surface temperature has been extremely high, with record temperatures far above average.

Near Cuba, sea surface temperatures were close to 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius) as Idalia passed by the island on Monday. As the storm moves north, it will pass over sea surface temperatures that are even warmer. By Wednesday morning, the storm is forecast to be over waters that are around 88° F (31° C) at the surface. That is very, very high.

The heat isn't just at the surface – the ocean heat extends deep into the upper ocean layer, or the thermocline, which is roughly 150 feet (50 meters) to 500 feet (150 meters) deep.

That accumulated heat provides fuel for the storm.

As the ocean temperature increases, the amount of water vapor available to the storm also increases.

Physics show that warmer air can hold more water vapor. With more heat and water vapor in the atmosphere, clouds heat up and the storm can rotate faster. It can also bring more intense rainfall.

Can wind shear weaken the hurricane?

A few things will weaken a hurricane. One is if the storm encounters cold water. Without warm water as a fuel source, the hurricane can no longer strengthen. In this case, however, the Gulf is exceptionally warm.

Wind shear is another important factor. Wind shear is a difference in wind speed and direction at different heights in a storm. Strong wind shear can tear apart a tropical storm.

That's common in the Atlantic basin during El Niño years like 2023. The question everyone has been asking this year is whether the wind shear will be strong enough to counter the extreme heat, and that doesn't appear to be happening with Idalia.

The wind shear was around 16 knots on Monday morning. By Wednesday morning, it was forecast to be about 21 knots.

That's moderately high but not enough to tear the hurricane apart – it's still going to rapidly intensify because of the heat.

That wind shear is still beneficial for people in the storm's path. Without it, a hurricane over water this warm could grow into a catastrophic Category 4 or 5 hurricane. Right now, it's forecast to be close to a Category 3, which is still dangerous.

Is global warming playing a role in hurricane intensification?

Long term, research shows Atlantic hurricane intensity has an increasing trend as the climate warms.

If you just look at wind speed, the average intensity of storms across all six major ocean basins isn't increasing. But rainfall intensity is a different story.

My research shows that over the past 20 years, tropical cyclone-induced rainfall has increased by about 1.3 percent per year on average across the world's basins and by even more in the Atlantic, about 1.6 percent per year. We linked the increase in rainfall intensity to increasing sea surface temperature and water vapor. Other researchers have found the same thing.

Each ocean basin is very different, and there are several reasons that the Atlantic may be seeing more intensification. One is that the Gulf is very warm, making it a source of strong hurricanes.

More intense rainfall can mean greater flooding potential, as large parts of Florida saw during Hurricane Ian in 2022. Even if wind speed isn't increasing in every basin, the damage can be higher because intense rainfall could also come from a storm's rain bands, not just from the eyewall.

Florida residents need to be aware of that risk as they prepare for Idalia to arrive.![]()

Haiyan Jiang, Professor of Earth and Environment, Florida International University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.