We're constantly learning more and more about the relationship between the bacteria living in our guts and our overall health, and a new study suggests certain types of these microbes can travel elsewhere in the body.

That would trigger the start of autoimmune diseases like liver disease and lupus in some cases, the research says – but it might also give us new ways to treat these illnesses if the specific bacteria can be targeted.

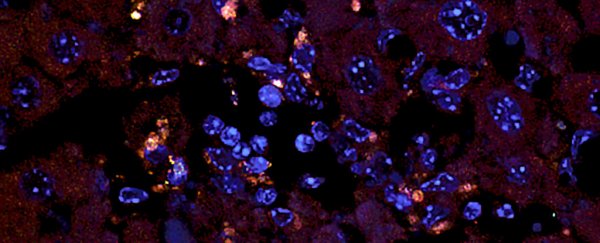

Researchers from the Yale School of Medicine in Connecticut were able to demonstrate this microbe migration happening in mice, as well as in cultures made of human liver cells. They also found evidence of gut bacteria in the livers of patients with an autoimmune disease.

"These bacteria don't stay in the gut," one of the researchers, immunobiologist Martin Kriegel, told Jon Christian at The Outline. "We found that they can go through the gut lining and appear in other organs."

The bacteria in question was Enterococcus gallinarum, one of the types that is known to cause the spread of infections in hospitals. The researchers found it could relocate itself out of mice guts to the lymph nodes, liver, and spleen.

While scientists already know microorganisms like these can escape the gut, before now it's only been seen as a response to triggers like inflammatory diseases or chemotherapy drugs. Here it seemed to be happening naturally.

Sure enough, the travelling E. gallinarum prompted the production of auto- antibodies and inflammation in the mice, the standard autoimmune response and potentially enough to spark off autoimmune diseases.

Further tests showed similar inflammation starting to happen in healthy liver cells cultured in a lab, as well as the presence of this bacteria in the livers of patients who already have an autoimmune disease.

The autoimmune symptoms in the mice could be reduced using antibiotics or vaccines, the researchers found – and that could be very significant in working out how to manage and prevent these conditions in the future.

"When we blocked the pathway leading to inflammation, we could reverse the effect of this bug on autoimmunity," says Kriegel.

Plenty more analysis is going to be required to pin down exactly how and why gut bacteria can escape their native habitat, but you can add this study to a growing pile of research that improves our understanding of the link between these microbes and the health of the human body as a whole.

Recent studies have linked gut bacteria to Parkinson's, for example, suggesting there's something in the connection between belly and brain that can trigger the disease. Other research says these bacteria can hold sway over our moods and emotions too.

With autoimmune diseases now added to the list, it's clear that the health of the tiniest organisms living in our guts can ripple out far and wide – whether or not the bacteria actually physically move – and the more we know about these processes, the better we can control them.

"Treatment with an antibiotic and other approaches such as vaccination are promising ways to improve the lives of patients with autoimmune disease," says Kriegel.

The research has been published in Science.