Researchers connecting pieces of the massive Alzheimer's puzzle are closer to slotting the next one in place, with yet another link between our guts and brain.

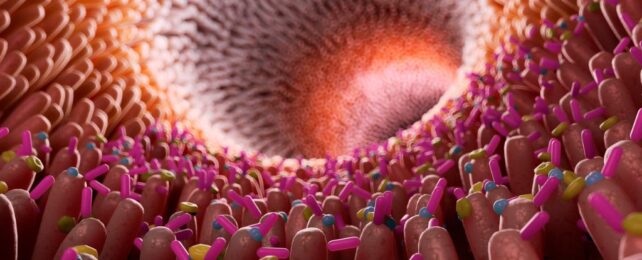

Recent animal studies have demonstrated Alzheimer's can be passed on to young mice through a transfer of gut microbes, confirming a link between the digestive system and the health of the brain.

A new study adds further support to the theory that inflammation could be the mechanism through which this occurs.

"We showed people with Alzheimer's disease have more gut inflammation, and among people with Alzheimer's, when we looked at brain imaging, those with higher gut inflammation had higher levels of amyloid plaque accumulation in their brains," says University of Wisconsin psychologist Barbara Bendlin.

University of Wisconsin pathologist Margo Heston and an international team of researchers tested for fecal calprotectin, a sign of inflammation, in stool samples of 125 individuals recruited from two Alzheimer's prevention cohort studies.

Participants underwent several cognitive tests on enrollment, as well as interviews on family history and tests for a high-risk Alzheimer's gene. A subset took clinical tests for signs of amyloid protein clumps, a common indication that pathology responsible for the neurodegenerative condition was underway.

While levels of calprotectin were generally higher in older patients, it was even more pronounced in those with Alzheimer's characteristic amyloid plaques.

Levels of other Alzheimer's disease biomarkers also increased with levels of inflammation, and memory test scores dropped with higher calprotectin too. Even the participants without a diagnosis of Alzheimer's had poorer memory scores with higher levels of calprotectin.

"We can't infer causality from this study; for that, we need to do animal studies," cautions Heston.

A laboratory analysis has previously shown gut bacteria chemicals can stimulate inflammatory signals in our brains. What's more, other studies have found increased gut inflammation in patients with Alzheimer's compared to controls.

Heston and colleagues suspect microbiome changes trigger gut changes that lead to system-wide inflammation. This inflammation is mild but chronic, causing subtle, incremental damage that eventually interferes with the sensitivity of our body's barriers.

"Increased gut permeability could result in higher blood levels of inflammatory molecules and toxins derived from gut lumen, leading to systemic inflammation, which in turn may impair the blood-brain barrier and may promote neuroinflammation, and potentially neural injury and neurodegeneration," says University of Wisconsin bacteriologist Federico Rey.

The researchers are now testing mice to see if diet changes associated with increased inflammation can trigger the rodent version of Alzheimer's.

Despite decades of research there's still no effective treatment for the millions of people with Alzheimer's worldwide. But with a greater understanding of the biological processes, scientists are getting closer, piece by piece.

This research has been published in Scientific Reports.