There's simply no denying the fact that humans have drastically altered, developed, and ransacked much of the natural world for our own ends. But how much of the planet's surface remains free of our often malign influence?

If we were to map Earth looking only for signs of humanity's footprint on landscapes, how much of the terrestrial surface would we find that had not already been built into cities, mined for resources, or razed to grow crops, instead of being left alone in an unaltered state?

In a new study, scientists compared figures from four different sets of spatial data to answer this question. While each of the datasets uses different kinds of methodologies and classification systems, on average, the researchers say roughly half (48 to 56 percent) of the world's land shows 'low' influence of humans.

"Though human land uses are increasingly threatening Earth's remaining natural habitats, especially in warmer and more hospitable areas, nearly half of Earth still remains in areas without large-scale intensive use," says environmental scientist Erle Ellis from the University of Maryland-Baltimore County.

(Riggio et al., Global Change Biology, 2020)

(Riggio et al., Global Change Biology, 2020)

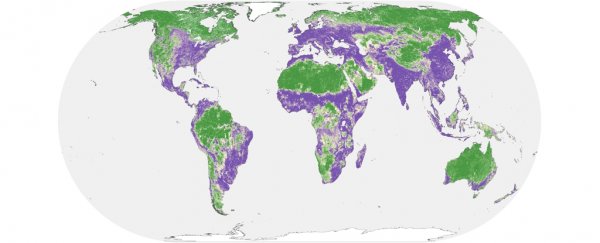

Above: Low human impact areas (green), with purple showing areas of higher impact.

While the figures may inspire many – highlighting the vast extent of significantly untouched lands that can still be protected via conservation measures – the study also serves to illustrate just how much of the Earth has already been occupied and utilised by the human enterprise.

As it stands, only about a quarter (20 to 34 percent) of the planet's ice‐free terrestrial surface shows 'very low' signs of human influence, the researchers say, and the parts of the planet that we have left alone up until now constitute some of the least inhabitable places on Earth.

From mitigating the impacts of climate change to recycling nutrients and providing fresh air, untouched land with fully functioning ecosystems plays an indispensable role for our ability to exist on this planet.

"Much of the very low and low influence portions of the planet are comprised of cold (e.g., boreal forests, montane grasslands and tundra) or arid (e.g., deserts) landscapes," the authors write in their paper.

"More concerning,

In other words, whether via urbanisation, forestry, agriculture, or other means, humans have exerted the most influence in biodiverse landscapes that presented ripe and easy opportunities for immediate human needs; in contrast, sweltering deserts in the world's hottest places, or frozen wastelands in its coldest climes, have been ignored.

Nonetheless, the researchers say the results shown here give us a strong, clear marker that we can use to help frame existing and future conservation efforts, by preventing encroachments on existing low impact areas, while simultaneously recovering areas for conservation in land that has already been exploited too much.

"Our findings suggest that ~50 percent of the terrestrial surface of the planet experiences low human influence and, as a consequence, it is possible to achieve bold global calls to proactively conserve at least 50 percent of the terrestrial planet," the researchers explain.

The study was conducted to help inform this year's Convention on Biological Diversity in China – a meeting that has been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Given the SARS-CoV-2 virus behind the outbreak is largely thought to be a zoonotic pathogen that spread to humans from animals, the postponement is just another example of how pressing these conservation issues are, the team says.

"Human risk to diseases like COVID-19 could be reduced by halting the trade and sale of wildlife, and minimising human intrusion into wild areas," says geographic information systems (GIS) researcher Andrew Jacobson from Catawba College in North Carolina.

Aside from protecting ourselves from pathogens, we need to act fast if we are to protect or restore lands that so far have been damaged by human hands.

Only about 15 percent of the planet is under some form of environmental protection, the researchers say, and intact ecosystems outside those places are rapidly being eroded.

There's a chance, right now, to draw a line in the sand, and say 'no more'.

"The encouraging takeaway from this study is that if we act quickly and decisively, there is a slim window in which we can still conserve roughly half of Earth's land in a relatively intact state," says conservation biologist and lead author of the study, Jason Riggio from UC Davis.

The findings are reported in Global Change Biology.