When something goes wrong in our bellies, we certainly feel it – and new research shows the processes through which harmful bacteria trigger pain in the gut, which clear out its contents in self-defense.

A team from the University of Oregon and the University of California, Irvine looked at one type of bad bacteria in particular: Vibrio cholerae (as you can tell from the name, that's the bacteria that causes the diarrheal disease cholera).

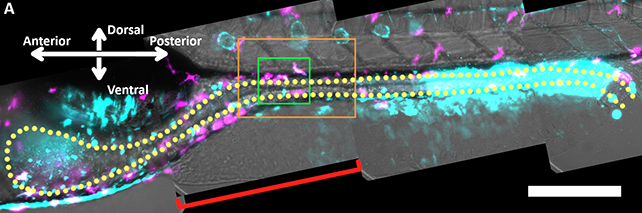

Having previously established that the bacteria leads to gut contractions in zebrafish, here the researchers wanted to take a closer look at the mechanism, discovering that it was physical changes in the gut rather than chemical messaging that caused the response.

Through an analysis of the bacteria's effect on zebrafish, the team observed immune cells called macrophages being redeployed to areas of tissue damage caused by the bacteria. That means the macrophages aren't doing their normal job of keeping gut neurons acting normally, leaving the abandoned neurons free to drive a serious level of gut pumping.

"It's amazing how dynamic all these cells are, the macrophages racing across the fish, the neurons and muscles pulsing with activity," says biophysicist Raghu Parthasarathy, from the University of Oregon.

"Without the ability to observe these phenomena in live animals, tracking cells and measuring gut contractions, we wouldn't have figured any of this out."

Not only are the immune systems of zebrafish more similar to humans than you might think – suggesting the findings here apply to our guts too – in the early part of their lives, these fish are semi-transparent, making it easier to see what's happening inside them.

While the end result of these stomach movements is painful and unpleasant if you've been hit by a bug, the response mechanism is actually beneficial for the body, as it clears out potential threats. It's beneficial for the bacteria too, enabling it to get rid of its rivals while moving on to other hosts sooner.

"If the macrophages have to go deal with an injury, then it actually makes a lot of sense for the neurons to freak out and just push everything out of the gut," says microbiologist Karen Guillemin, from the University of Oregon.

"If there's something in the gut that's causing injury, you want to get it out of there."

The researchers say there's lots more to investigate here, in particular in the way the nervous system and the immune system work in tandem to fight infection and keep the body healthy.

For now, we have a better understanding of how the gut reacts to invading bacteria. The discoveries here are likely to apply to many other bacteria types too, and could eventually help inform treatments for conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

"This isn't a specific nefarious activity of the Vibrio bacteria," says Guillemin. "The gut is a system where the default is, when there's damage, you flush."

The research has been published in mBio.