In the murky depths of the ocean, one predator has a trait that exacerbates the dread it inspires as it slides through the ocean waves. Sharks have long been considered completely, eerily silent; to the point that it has become an integral part of their mythos.

This reputation may be unearned. For the first time, scientists have recorded sharks actively making noise, a loud clicking sound made by rigs (Mustelus lenticulatus) – a discovery that reveals a whole possible dimension of shark communication that has eluded us until now.

"I was very surprised," Carolin Nieder of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute told ScienceAlert. "I was under the assumption that sharks don't make sounds."

What we don't know is what the active sounds, which you can hear below, mean. But we now have a whole new avenue of research for understanding these enigmatic, overly maligned denizens of the oceans.

Sound travels long distances underwater, and many animals have apparatus for making noises. These sound makers are incredibly diverse, including swim bladders, specialized muscles, and raspy surfaces to scrape against each other to create stridulation noises.

Elasmobranchs – the family of cartilaginous fish that includes sharks and batoids (skates, rays, and sawfish) – are not known to possess any specialized sound-making physical features. So it was a big surprise in 2022 when scientists discovered two species of ray making deliberate clicking noises.

Another three species of batoids subsequently revealed their percussive songs, and scientists pricked up their literal as well as metaphorical ears. Could there be a whole area of elasmobranch communication that we simply didn't know existed? What other elasmobranchs might be sending out secret communiques?

Nieder and her colleagues decided to start their investigation with rigs in the estuaries of New Zealand.

There were two main reasons for this. Firstly, rigs are relatively small, and fish small enough to be held in the hand are excellent for this kind of research, since they can be tested and recorded in standardized conditions. Secondly, the researchers had received anecdotal reports of clicking sounds made by schooling rig juveniles in the wild, in addition to their own experience with the species.

"Back in 2021 I used behavioral training experiments combining food and sound which also included some handling. During these experiments, I happened to notice that one of the shark species made a clicking noise when being handled underwater," Nieder said.

"At first, we thought it might be a strange artifact. However, with time, as the animals got used to the daily experimental protocol, they then stopped making the clicks all together, as if they got used to being in captivity and the experimental routine. This led us to consider that maybe we are observing a sound-making behavior rather than a strange artifact."

Between May 2021 and April 2022, the researchers obtained and recorded 10 juvenile rigs, between 55.5 and 80.5 centimeters (22 and 32 inches) in length, five male and five female. Each shark was placed in a small experimental tank, and handled by the researchers.

While they were being handled for 20 seconds, the sharks made short, high-frequency clicks, averaging about 48 milliseconds per click, with a mean peak frequency between 2.4 and 18.5 kilohertz. A sound at 2.4 kilohertz can be heard in the video below. Most adults can only hear up to 17 kilohertz; there's a sample of 18.5 kilohertz here, but you may not be able to hear it.

The sounds were recorded by a microphone roughly 30 centimeters from each shark at a volume up to 166 decibels, on a par with a handgun or firecracker. So the clicks do not exactly represent a shark whisper.

Every single shark in the study was recorded making clicking noises when handled. They did not make any noise while swimming freely or feeding in the tank, and they made more noises in the first 10 seconds of being handled than in the second 10 seconds, leading the scientists to hypothesize that the clicks are a distress response that may diminish over time as the sharks become accustomed to handling.

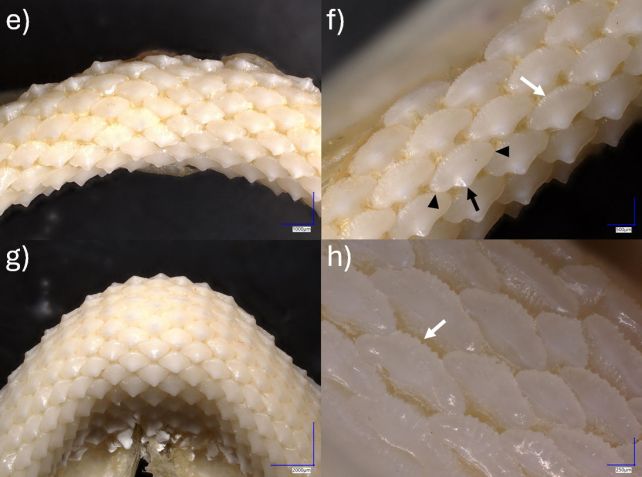

The second part of the study involved trying to figure out how the noises are made. The researchers think that the sharks snap their jaws together with force, smacking their teeth together to make a loud, percussive clicking sound. We don't know for certain yet, but it seems like the likeliest explanation.

"Within the limits of the available data, the broadband frequency range and short duration of the rig clicks suggest the involvement of teeth snapped during rapid mouth closure for sound production," the researchers write in their paper. "However, additional investigations will be necessary to test this hypothesis."

We also don't know if rigs are able to hear the clicking sounds they make. This means more work will need to be done to determine if they have a purpose. If they can't hear their own noises, that could mean that it's just an incidental response to being startled.

However, if they are capable of hearing the sounds, that could mean that the noises are a way to communicate with other sharks.

"One possibility could be that the sounds are a form of a startle response (in the wild perhaps in response to an attack by a larger shark or marine mammal)," Nieder told ScienceAlert.

"Scott Tindale (Tindale Marine Charitable Trust), who dedicates his life to tagging sharks and other fish all around New Zealand and Australia and who happened to hear similar clicks rigs in the wild, even before I noticed them, thought that perhaps the rigs try to imitate snapping shrimps (part of their diet) to lure them out of their burrows in the sediment to then attack them. I think that is a very interesting theory as well."

The team's research has been published in Royal Society Open Science.