Hearing aids may have the potential to delay some cases of Parkinson's disease, according to compelling new research.

Among more than 3.5 million veterans in the United States, researchers have found those who experience hearing loss are more likely to be diagnosed with Parkinson's disease later on.

The more severe the hearing loss and the longer it occurs for, the more likely that outcome. But if hearing aids are prescribed right off the bat, the risk of diagnosis appears significantly dampened.

The findings add to growing evidence that suggests hearing loss is associated with neurodegeneration, and that hearing aids are a low-cost, low-risk intervention that can help keep the brain healthy and fit as a person ages.

In 2022, a systematic review found that among adults who are hard of hearing, those who manage their condition with hearing aids are 19 percent less likely to show signs of cognitive decline than those who do not.

In 2023, a landmark clinical trial put that association to the test and found hearing aids may slow the rate of cognitive decline by nearly 50 percent in some older adults.

Like dementia, Parkinson's is commonly associated with cognitive decline. Today, it is well-established that vision issues and a loss of smell can precede the physical symptoms that qualify a Parkinson's diagnosis, like slow movement, stiffness, and tremors. But this is the largest and most rigorous study yet to examine the role of hearing loss.

"It may be the most important modifiable risk factor for dementia in midlife and could prove to be the same for Parkinson's disease," write the research team, led by neurologist Lee Neilsen at Oregon Health and Science University and the Veterans Affairs Portland Health Care System.

To start off, Lee and his team tested a cohort of mostly White, male, middle-aged veterans for mild, moderate, severe, or profound hearing loss. The cohort was then tracked for the following two decades.

The team says their data provides "strong evidence that hearing aid administration reduces Parkinson's disease risk on a population level."

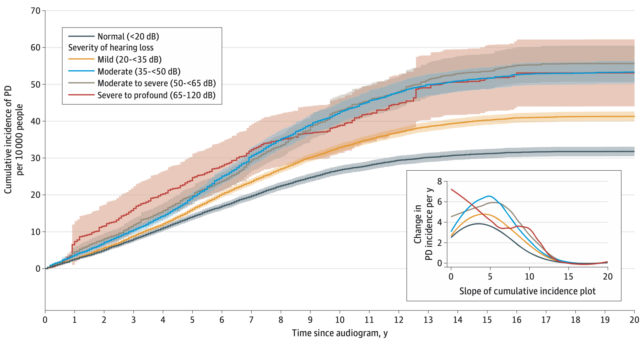

Compared to those with healthy hearing, veterans with mild hearing loss (usually those in their 60s) had a greater cumulative incidence of Parkinson's at five, 10, 15, and 20 years follow-up.

Two decades on, researchers found an additional 10 cases of Parkinson's per 10,000 individuals that were tied to mild hearing loss.

The good news is that those who received a hearing aid before or just after the study's initial hearing test were less likely to develop Parkinson's compared to those who did not. The difference between these groups was apparent as early as one year into the study.

Randomized clinical trials are now needed to explore that association further.

It is unknown, for instance, if hearing aids are restoring or restrengthening lost neural connections, like regular exercise can restore and restrengthen muscles, or if hearing aids take strain off the brain's energy reserves, allowing for easier functioning.

It could also be the case that hearing aids improve social interactions or alleviate depression or loneliness, all of which can contribute to cognitive decline.

In the current study, those who experienced hearing loss in conjunction with other early markers of Parkinson's, like sleep issues, vision impairment, or loss of smell, had an even higher risk of being diagnosed down the road.

Given that mild hearing loss is associated with the disease, Lee and his colleagues argue that "hearing screening should be enforced at the primary care level even in the absence of a patient expressing hearing concerns".

The study was published in JAMA Neurology.