In the savannahs and rainforests of tropical Africa, an ape friend once made is a friend for life.

A study on 26 captive chimpanzees and bonobos led by Harvard University evolutionary biologist Laura S. Lewis, who was a student at Stanford University at the time of the study, has found non-human apes can recognize family members and friends they haven't seen in decades.

A 46-year-old bonobo at the Kumamoto Sanctuary in Japan named Louise showed signs of recognizing two relative bonobos she hadn't seen since 1995 – a whole 26 years later.

That's the longest-lasting social memory recorded in any non-human animal, and the findings could help explain how we ourselves evolved the ability to remember thousands upon thousands of faces for decades on end.

The experiments were conducted at various institutions around the world, including the Kumamoto Sanctuary, Edinburgh Zoo in Scotland, and the Planckendael Zoo in Belgium.

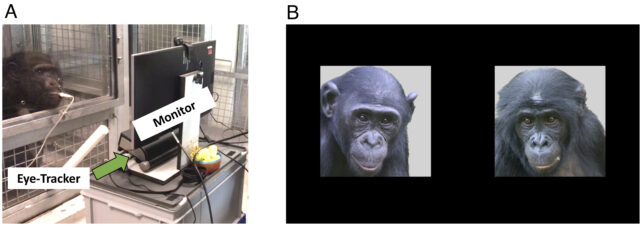

Each chimp or bonobo enrolled in the study was familiarized with a computer, which was then used to display two side-by-side photos to the ape while they sipped on some juice.

One photo displayed a face unknown to the viewer, and the other displayed the face of an old friend, relative, or foe that the ape had lived with for at least a year in the past.

While looking at the photos for just three seconds, an eye-tracking tool watched the participant's visual attention closely.

"It was a really simple test: Do they look longer at their previous groupmate, or are they looking longer at the stranger?" explains Lewis.

"And we found that, yes, they are looking significantly longer at the pictures of their previous groupmates."

As our closest living relatives, it really shouldn't come as a surprise that chimps and bonobos are drawn to faces they have seen before. Primatologists like Lewis have noticed that chimps and bonobos seem to recognize their human caretakers after significant chunks of time apart.

Yet historically, the scientific establishment has underestimated the social life and memories of other animals.

Thanks to the curiosity of scientists like Lewis, that is slowly starting to change.

In 2013, researchers found that dolphins can recognize the signature whistles of their kin after 20 years spent away from each other.

Just this year a study found elephant mothers and daughters can recognize each other's scent after as many as 12 years apart.

The new study on chimps and bonobos supports the idea that we and our ape brethren share similar facial processing mechanisms, which we use to form lasting and potentially lifelong relationships.

"We don't know exactly what that representation looks like, but we know that it lasts for years," says Lewis.

"This study is showing us not how different we are from other apes, but how similar we are to them and how similar they are to us."

Lewis and her colleagues found that apes attended more to the familiar faces of old friends with whom they'd had closer relationships than those they were less bonded to.

This could suggest that long-term facial recognition evolved more as a tool for cooperation than competition, although that would require further experimentation.

The duration of time spent apart didn't seem to change the results.

"Although more data are needed to determine whether great ape memory lasts beyond 26 years," Lewis and her colleagues write, "these results indicate that, for at least some nonhuman great apes, the longevity of social memory may be relatively similar to that of humans, which begins to decline after ~15 [years] but can persist 48 years beyond separation."

If Lewis and her colleagues are right, the long-term memory of faces could reach back to our last common ancestor with apes, more than 6 million years ago.

The study was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.