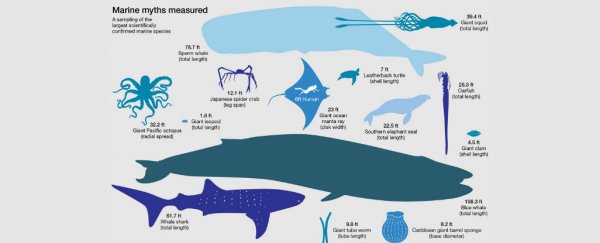

According to British science writer Ed Yong over at National Geographic, the idea for this infographic (which you can see a larger version of here) sprung from a science writing workshop run by himself and science writer Carl Zimmer a few years about how to explain science to a general audience without talking down to them.

"I made a comment about how I always wanted to write a post on how giant squid sizes are bullsh*t, but that those always come off as an arrogant scientist telling the world that it's wrong," Craig McClain, the assistant director of the National Evolutionary Synthesis Centre in the US, told Yong.

Instead, McClain teamed up with Meghan Balk from the University of New Mexico in the US, and together they led a group of undergraduate students and several researchers, whose job it was to find the most accurate estimates of the size of the ocean's 25 largest species, and to clear up the many misconceptions that have been shared around for decades. Species include the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), the giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini), the walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), the giant tube worm (Riftia pachyptila) and the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni).

Problems with accuracy can be due to many different factors, such as how decomposition causes the muscles and sinew of dead sea creatures to stretch to ridiculous lengths, coupled with the fact that we rarely, if ever, catch enough of a glimpse of these creatures in situ to measure them in life. This is particularly true with the deepest-living fish species - often we can't bring them to the surface without killing them - and squids.

"Several years ago I noticed that people kept staying that giant squids reached 60 feet [18 metres] in length, which is amazingly long," said McClain in a press release. "When I started actually looking at the data, I found that that estimate was actually quite unrealistic."

What McClain and his team found, after poring through the scientific literature, books, newspaper clippings, museum specimens, and talking to scientists out in the field, was that most giant squids only ever grow to be about half that length, and the largest verifiable measurement of a live giant squid was 12 metres. Big, but still no where near the oft-cited 18-metre figure.

One of the least accurate measurements that had been reported as fact had actually been measured by some guy counting his paces alongside a stretched-out, decomposed squid on the beach. As Yong notes at his National Geographic blog, Phenomena, "Shoddy data had been unleashed upon the kraken."

Another factor that's led to inaccurate data on the size of the ocean's biggest animals is that times have changed. Just because squids or sharks or crabs grew to a certain size 50 or 60 years ago doesn't mean they can achieve that amount of heft today. They've got pollution, climate change, culling, and overfishing to adapt to. On the other hand, some creatures, such as the red lionfish (Pterois volitans), are getting progressively bigger, after having been dumped in the Atlantic Ocean by humans in the 1990s, where they have no direct predators.

The team published their measurements, and the infographic above, in the journal PeerJ.

The point of the study, they said, was one part research, one part outreach. The results? Well, we now know that the largest arthropod leg belongs to the Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi), and it's 3.7 metres long. The largest bivalve is the giant clam (Tridacna gigas), with a shell length of 137 cm. The largest octopod is the giant Pacific octopus, and that thing is 9.8 metres long. But all of that's nothing compared to the longest known medusozoa, the Lion's mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata), with tentacles that could possibly stretch over 36 metres (see the paper for questions about this though.)

"Precise, accurate, and quantified measurements matter at both a philosophical and pragmatic level," said McClain in the press release. "Saying something is approximately 'this big,' while holding your arms out won't cut it, nor will inflating how large some of these animals are."

Sources: Phenomena, EurekAlert