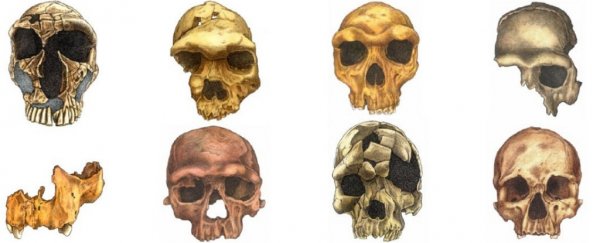

The human face is unique yet universal, mechanical yet expressive, modern yet ancient. For over 4 million years, our features have slowly morphed into what we see today in the mirror, a brief stop on the way to who knows what.

From early hominins to modern Homo sapiens, a new review written by leading experts traces the history of the human face across millions of years, as landscapes, climates, and cultures come and go.

Like many before them, the international team agrees that diet and climate were important factors in shaping the human face. Still, there's another element they think is too often overlooked: social necessity.

"We know that other factors such as diet, respiratory physiology, and climate have contributed to the shape of the modern human face," says anatomist Paul O'Higgins from the University of York, "but to interpret its evolution solely in terms of these factors would be an oversimplification."

Using facial skin, bones, and muscles, modern humans can signal more than 20 different categories of emotion to one another. And that's not something we could always do.

As the human face evolved over millennia, it went from a stiff mask to an easily-manipulated mug: "a short-faced cranium with a large globular brain case," as the authors put it.

With the dawn of a smooth forehead, our eyebrows were officially unleashed with plenty of room for movement; at the same time, our faces grew smaller and more slender, allowing for subtle emotions like recognition and sympathy.

Suddenly, there were more opportunities than ever before for gestures and non-verbal communication - a vital step if humans were to establish and maintain large social networks.

"We think that enhanced social communication was a likely outcome of the face becoming smaller, less robust, and with a less pronounced brow," says one of the authors, Rodrigo Lacruz, a craniofacial biologist at New York University.

"This would have enabled more subtle gestures and hence enhanced non-verbal communication."

It's doubtful that social communication could have reshaped the modern human face all on its own, but the authors think it should at least be included in leading theories.

Diet, for instance, is one of the most cited factors in explaining our facial shape. Unlike modern humans, early hominins ate tough plant foods, tearing through them with their teeth alone. As such, they needed large jaw muscles, and these massive attachments required broad and deep faces.

In the past 2 million years, however, humans have started using tools to break down and cut our food. And as we've learned to process and cook it, our faces have begun to shrink.

(Lacruz et al., Nature, 2019)

(Lacruz et al., Nature, 2019)

"Softer modern diets and industrialised societies may mean that the human face continues to decrease in size," says O'Higgins.

"There are limits on how much the human face can change however; for example, breathing requires a sufficiently large nasal cavity."

It's a trend that's been going on for some 100,000 years, and with climate change becoming an ever-growing problem, it too could be affected.

With temperatures increasing, the authors say it could change our appearance. If climate predictions are correct, they argue we might expect changes in our nasal cavities, which help warm and humidify air before it enters our lungs.

"We are a product of our past," says human evolution expert William Kimbel from Arizona State University.

"Understanding the process by which we became human entitles us to look at our own anatomy with wonder and to ask what different parts of our anatomy tell us about the historical pathway to modernity."

This study has been published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.